Smrekar and Cankar

For an artist who had begun his creative career among the waves and swirls of the heightened individualism of fin-de-siècle and Belle Époque art, such an understanding – or indeed a conceptualisation – of the self is unusual. Even strange. For a caricaturist, whose art is based on the exaggeration of natural proportions and physiognomy, the flight from the sovereignty of one’s own ego into the idea or notion – never entirely watertight – of another human being is a surprising one. It is evidently a question of dispelling uncertainty – an attempt to reinforce one’s own vision and understanding with an authority that is recognised by many.

Yet a duplication of identity does not always mean identification. Smrekar’s art did not suffer as a result of his ego’s aspiration to become the eye of another. Quite the opposite: in this unusual position for an artist, it quickly revived and rapidly grew sharper, and then also changed. Ivan Cankar travelled a long road after his youthful break with the cultural establishment. At first he rebelled anarchically against everything (the endless catalogue of his targets included not only institutions and organisations but also orchestrated revolution directed towards inevitable philistinism, and reality that was in thrall to the concept of society). Later he became the critical voice of the Slovene world and was a restless seeker and tireless innovator. But his element was the written word. With the exception of a few drawings – mainly sketches in the margins of his plays – he did not express himself through art. He was in no sense a rival or hindrance to Smrekar. Instead, he was a support. An encouragement. And, with his constant stream of new works, also an inspiration. And a criterion. Smrekar was able to remain unique in his own creative field, despite equating his own real spiritual biography and the basis of his personal understanding of the world with those of the writer. Cankar had many imitators among other writers, but none was his true successor. Neither an heir nor a continuer. Smrekar, who was not Cankar’s epigone – and only occasionally a mere illustrator of his works – became both. He was more bound to the writer more fatefully. More deeply. More personally.

Smrekar’s understanding of himself through Cankar provided him with unique “autothematic” subject matter. The many depictions of the writer he left behind are a kind of seismograph of his moods. It is not a matter of physical appearance but of spiritual self-image, expressed through his relationship with elements of reality and fantasy.

Smrekar’s restless artistic expressivism is characterised by the satirisation and grotesquification – the rendering grotesque – of reality. The latter remains an all-connecting reference point that must be discovered in order for the artist’s creation to be understood in its multilayered totality. The depictability of people, things and phenomena does not depend on their appearance – which in essence is nothing other than the protecting of the essential interior with a protean exterior – but on the astuteness and boldness of the gaze. But satirisation and grotesquification are also transrealistic stylisations found in Cankar’s literature; at least at the microstructural level, they combine with two other artistic processes – symbolisation and oppositionalisation (e.g. between fantastic and factual “scenes”). These may be encountered in all the writer’s creative periods. And in all the genres he tackled.

Consequently, it should surprise no one that Cankar is the most conspicuous figure in Smrekar’s two group depictions of Slovene writers – works that are thoroughly pervaded by satirisation and grotesquification. Not only that, but in both of these ironically conceived “class photos” of the wizards of the written word, both dating from 1913, a good part of the emphatic arsenal of the fine arts is placed at the service of Cankar’s conspicuousness. (Figs 1, 2.) The figure of Cankar, who, unlike most of the others, attempts no kind of interaction with his brothers of the pen (and cousins in terms of influence) – he doesn’t even look at them – is one of the smallest, yet it attracts the attention because of the drastic discrepancy between the size of the full-length portrait and the weight of his oeuvre. It actually cries out for a protest or a comment. The image thus continues into an idea. The artist’s literary alter ego also attracts the viewer’s gaze because of its position in the overall composition. In a picture in which Slovenia’s knights of the pen are depicted as carnival participants, he is shown wearing a crown – although this reveals itself to the more attentive observer as a combination of a sovereign’s insignia adorned with pearls and a jester’s cap of bells. In the second picture, in which the writers are not in costume but dressed in clothes that accentuate their characters, Cankar is portrayed as a foot-stamping enfant terrible – with dishevelled hair. Yet none of his colleagues see him: they are all looking elsewhere.

Fig. 1

Slovenian Literati, 1913, National Musuem of Slovenia

Fig. 2

Masquerade of Slovenian Literati, 1913, National Gallery of Slovenia

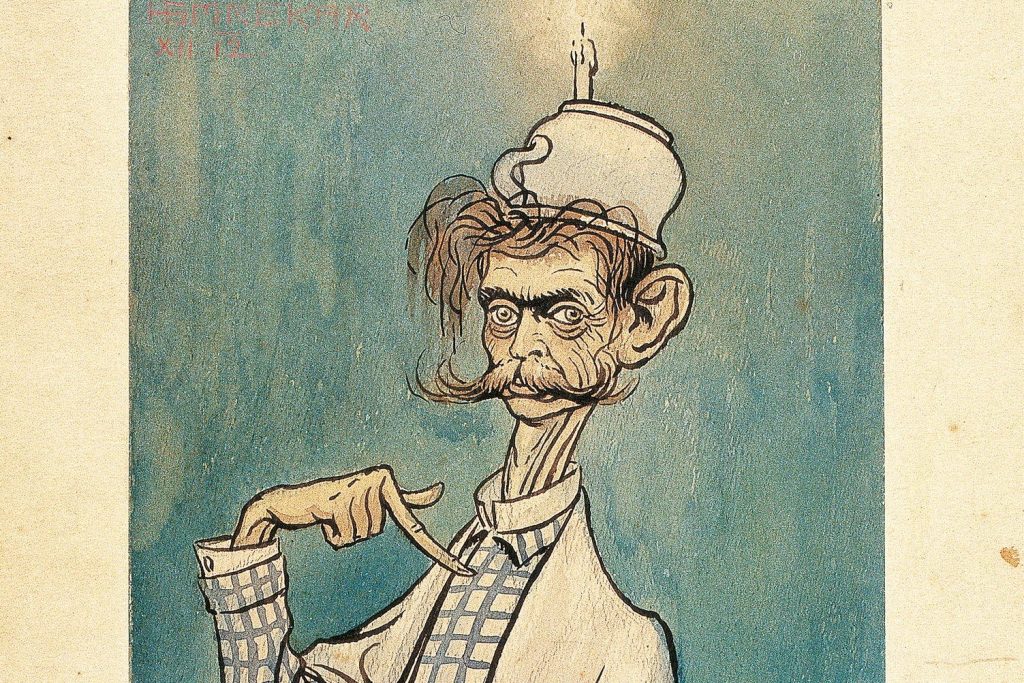

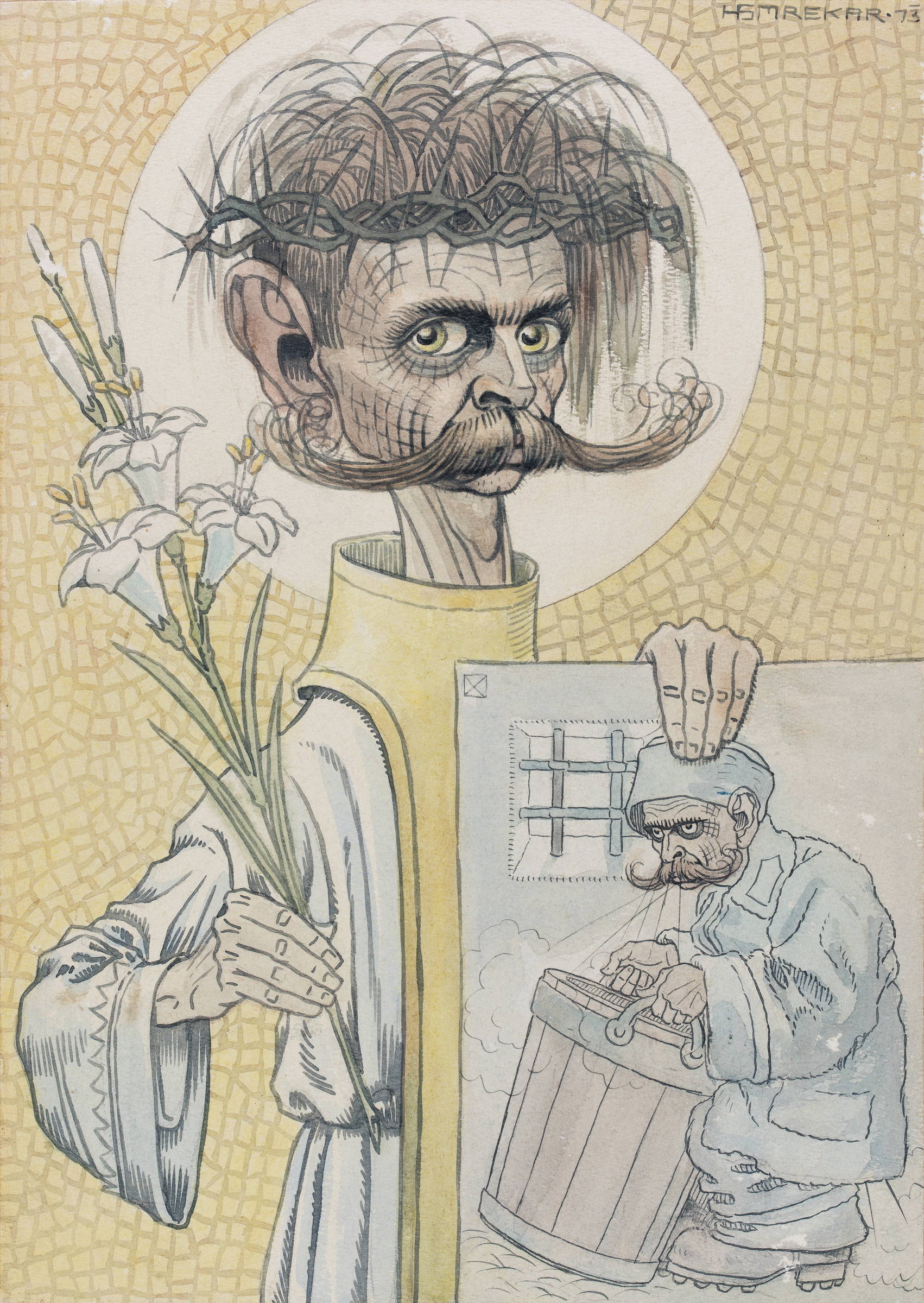

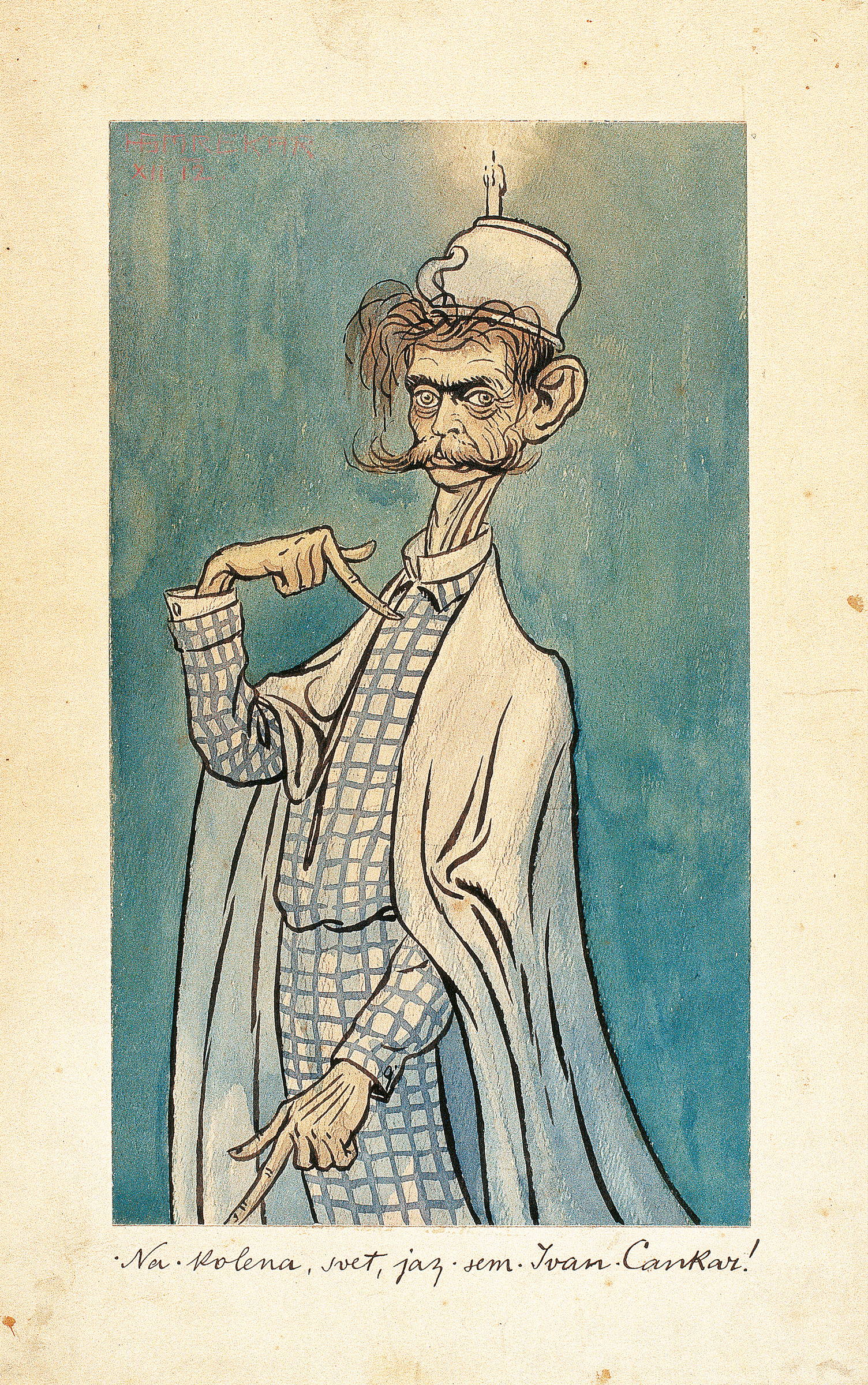

Cankar, who draws Smrekar’s attention in every situation, is not a monumental figure but a thoroughly vital personality. He possesses many expressive and experiential registers. Metaphorical and perspectival transformations on the one hand problematise and, on the other, highlight every obviousness, although it is not their intention to demolish or even degrade his role in the public space. Even as a prisoner, the writer remains what he is. (Fig. 3.) And even in the most grotesquely caricatured position, he is able to introduce himself self-confidently: “On your knees, world, I am Ivan Cankar!” But the prince of the Slovene written word was ever thus, not only in Smrekar’s depictions: semantic polyvalence was intrinsic to him. (Fig. 4.) With his sarcastic (re)potentiation and negative depictions of reality, he always included the possibility of creating an illusory impression of identification between the world and his interpretation. Cankar had already abandoned this widespread artistic strategy – often intensified to the level of aesthetic normativism – in his programmatic Epilogue to his Vignettes in 1899: at that time he expressly tied the birth of art to the unique creative personality. Even in the introduction to Images from Dreams, which, with its defence of the authenticity of expression and the search for the right word, is a unique manifesto of Slovene literary expressionism, he did not renounce creative spiritual personalism. He simply became aware of its common meaning and mission – a focus on everyone. Art wanted to be an expression of life, not its mimetic repetition.

Fig. 3

Ivan Cankar ‒ Jailbird, 1913, private collection

Fig. 4

Ivan Cankar, 1912, National Gallery of Slovenia

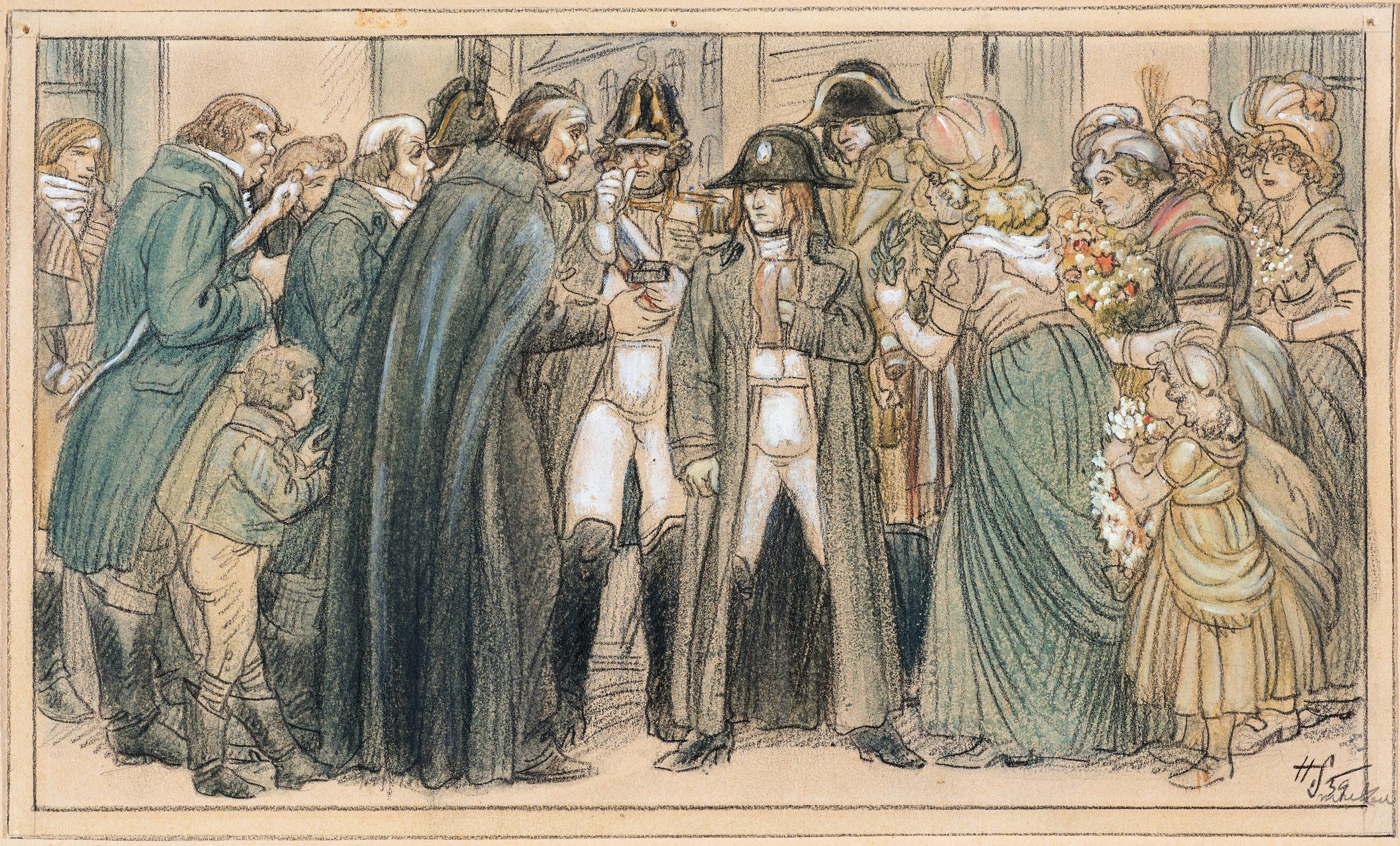

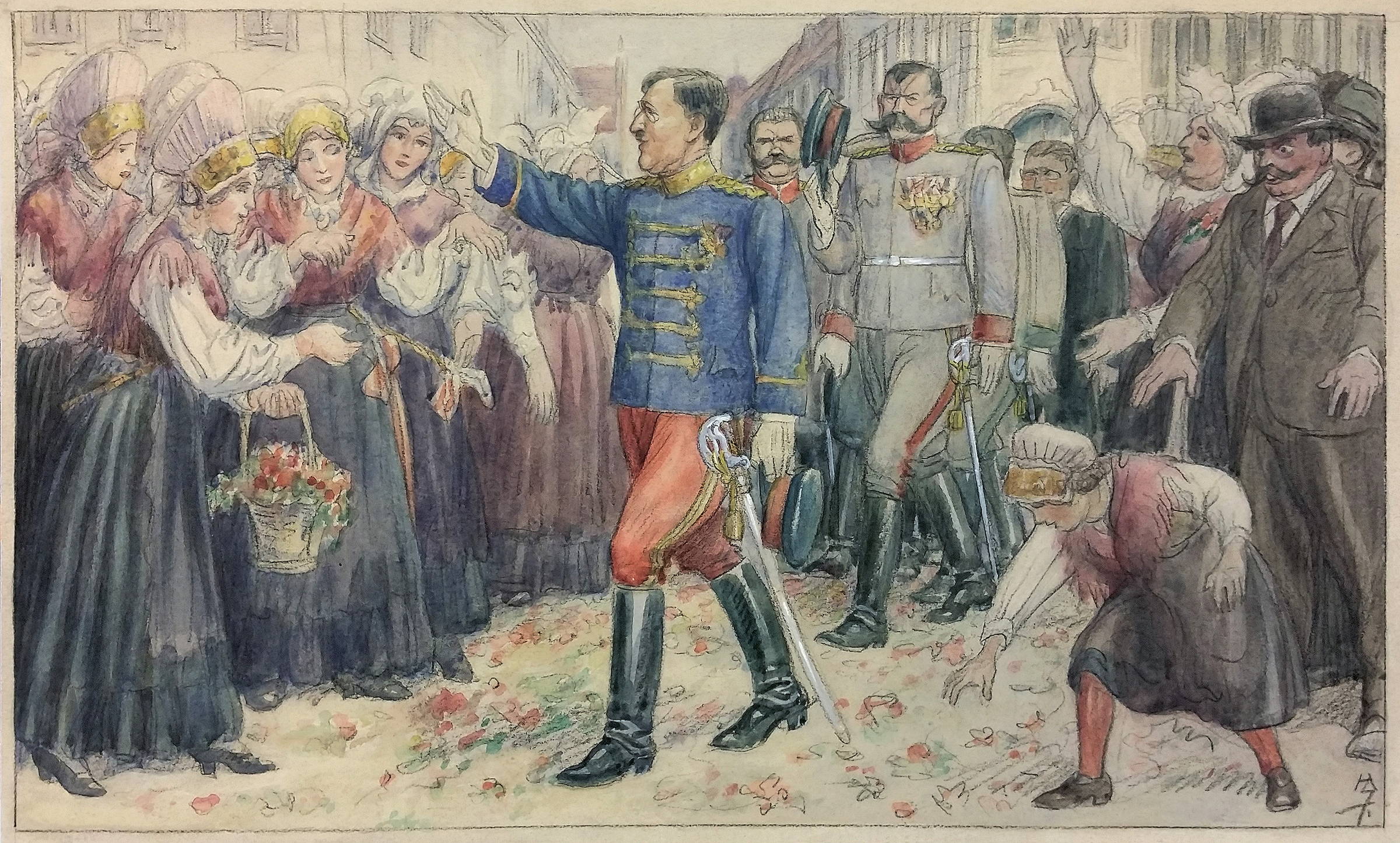

It was between these coordinates that Smrekar spread the canopy of his own creativity, having constantly oscillated between masterful criticism of reality and a feverish search for support – first from his mother, then from Cankar and finally from doctors. It was only in 1939, in the oppressive mood before the outbreak of the Second World War, when he was making a less than convincing attempt at augmenting the modest corpus of Slovene monumental historical painting, that he turned his gaze – perhaps unironically for a moment – at everything evoked by the notions of country and society. (Figs 5, 6, 7.) And the result was neither satisfying nor heartening. The new times placed reality – which, unlike creative imagination, always ends in death – in a place previously occupied by the bitterest grotesque. And the crown which Smrekar had once won for himself in the kingdom of Slovene artistic irony now put forth thorns.

Fig. 5

Enthronement of the Duke of Carinthia, (1939), private collection

Fig. 6

General Bonaparte l. in Ljubljana in 1797, (1939), private collection

Fig. 7

King Alexander in Ljubljana, (1939), private collection

Author: ddr. Igor Grdina, 2022