I am convinced of the fact that if I should happen to die, the loss for the Slovenian nation will be greater than for me, whether the glorious Slovenian nation is aware of it or not. A nation for which culture and cultivation are an unnecessary and annoying luxury is no nation at all.

Illness and Treatment

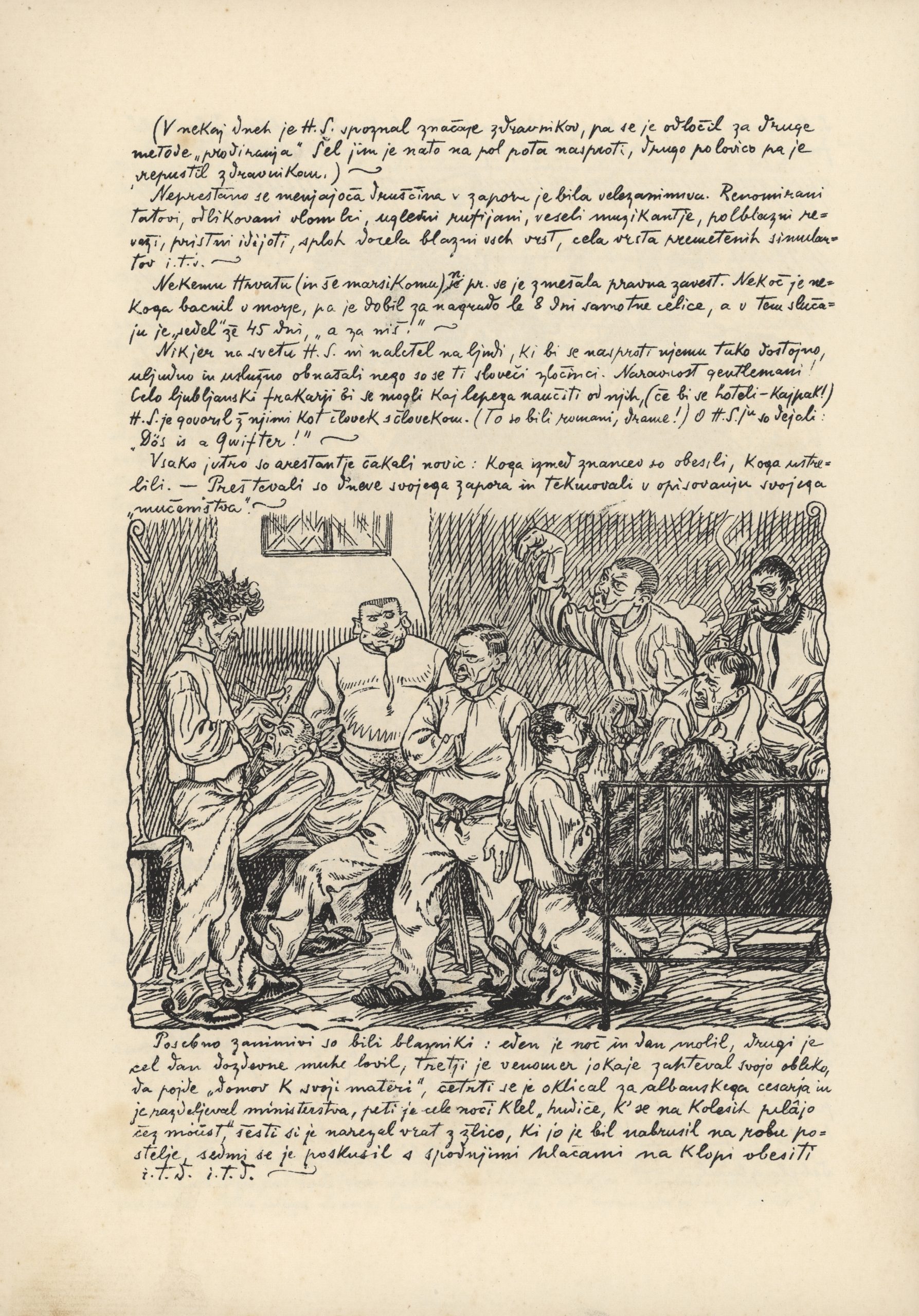

Fig. 1

Hinko Smrekar

The Burial of the Slovenian Art Reprobates, illustration from the letter to the Glorious Provincial Council

4. 10. 1916

National and University Library, Manuscript Department, Ljubljana

Smrekar describes his life as an internee during the war in great detail in his illustrated autobiography Henrik Smrekar – črnovojnik (Henrik Smrekar – Landsturm soldier) (1917–1919). This work includes accounts and depictions of several medical examinations, the lengthiest and most laborious of which was Smrekar’s army medical at the garrison hospital in Graz. At these examinations he apparently pretended to be suffering from paranoia. (Fig. 2)

His fellow prisoners gave him advice and instructions on how to “go insane — in the most practical way”. During the ward round, Smrekar apparently feigned madness by hiding under a blanket and shivering. As the doctor consoled him, Smrekar said, abruptly and frantically, that R. Jakopič, the Pope of Slovenian Painting, was trying to destroy him, that the wife of Jakopič had connections everywhere and was agitating against him, and that the doctor was a hypocrite. After long and agonising observations and examinations, he was discharged as completely unfit for military service.

We can learn more about the course of Smrekar’s illness from the petition that he sent to the Student Mutual Aid Society “Radogoj”, in which he writes that wartime political persecution had taken its toll on him and he had contracted the Spanish flu, which had gone untreated as he had to take care of his sick mother, performing the duties of a housekeeper and nurse in addition to his work. Then he had a recurrence of the pulmonary infection which he had contracted while on military service. As he could not afford to stop working, the neurasthenia that had already afflicted him during his studies returned. In September 1919 he was in a state of “complete nervous exhaustion and collapse.

After a very productive and varied decade, Smrekar found himself in a creative lull of several years, due to his health problems and treatment in various health resorts which resulted in fewer commissions.

On 9 December 1920 Smrekar went to the Laßnitzhöhe health resort near Graz, where he remained intermittently until 13 April 1921. His letters swing from optimism to the extreme pessimism of bidding farewell to life. A medical certificate from his physician, Dr Eduard Miglitz, dated from February, states that the patient showed symptoms of “irritable nervous weakness with mood irregularities and labile feelings of hypochondria”. Miglitz added that the treatment had led to a significant improvement and calming down of the patient, who would soon make a full recovery, but that further treatment would still be necessary later.

I cannot be accused of having seduced her frivolously, I resisted for a long time, it was she who tempted me with her demeanour, and so I was drawn into the relationship! I resisted and restrained myself the entire time and was angry with the whole thing, in particular a) for getting involved in the first place, and »b) for getting involved with her — the anger over this has ruined me. /…/ As a result of this permanent erotic irritation, of self-restraint and anger at myself, and because she told me to forget her just when I was the most irritated — as a result of all this I became permanently ill /…/ The important point, perhaps the most important, was that at the same time I had to struggle with my lungs and the “heiratitio” (matrimonial instinct). In my opinion, this point was not sufficiently considered by the doctors.

From a note dated 17 April 1920, in which Fran Vesel reports what Smrekar said to him.

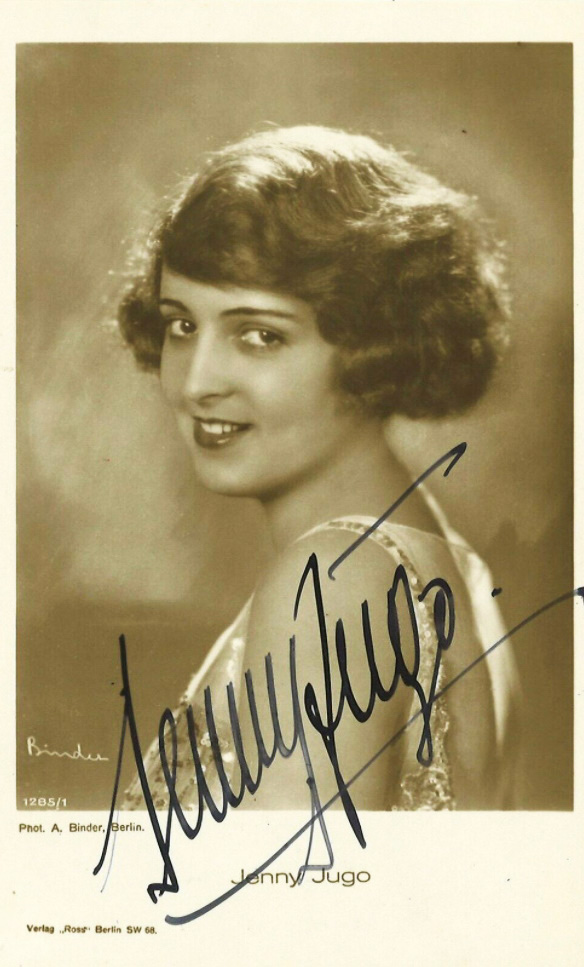

Smrekar was in despair and convinced that he would die among strangers in the health resort. He had befriended Jenny, a fickle and “somewhat hysterical” 17-year-old with whom he was “playing the fool”. He kept assuring her that she would get somewhere in life and that she would make a career in the theatre. And indeed, Jenny Jugo would become a successful actress, starring in more than 50 films. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3

Alexander Binder

Jenny Jugo (real name Eugenie Walter, 1905‒2001), (1926)

Source: Wikipedia

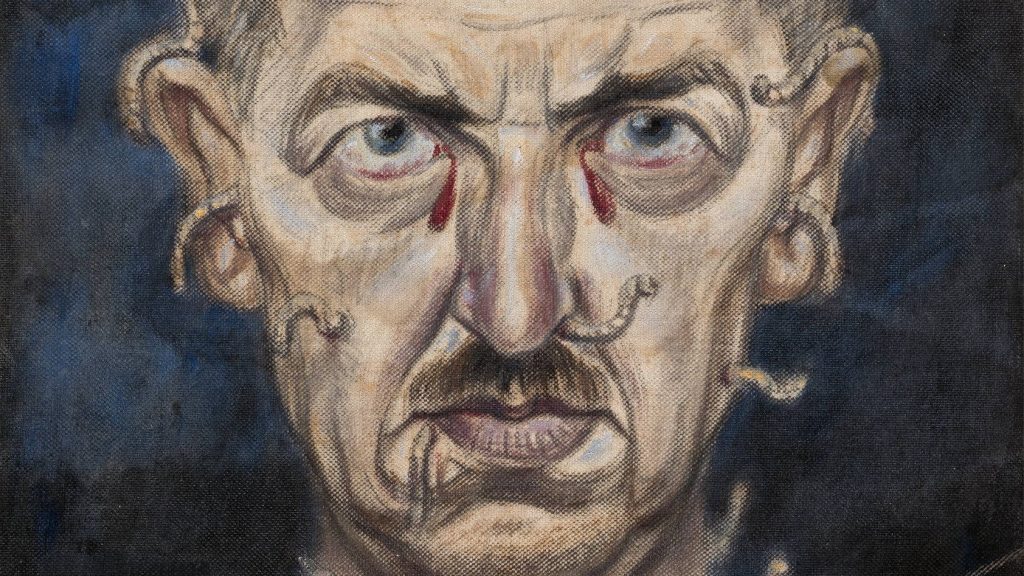

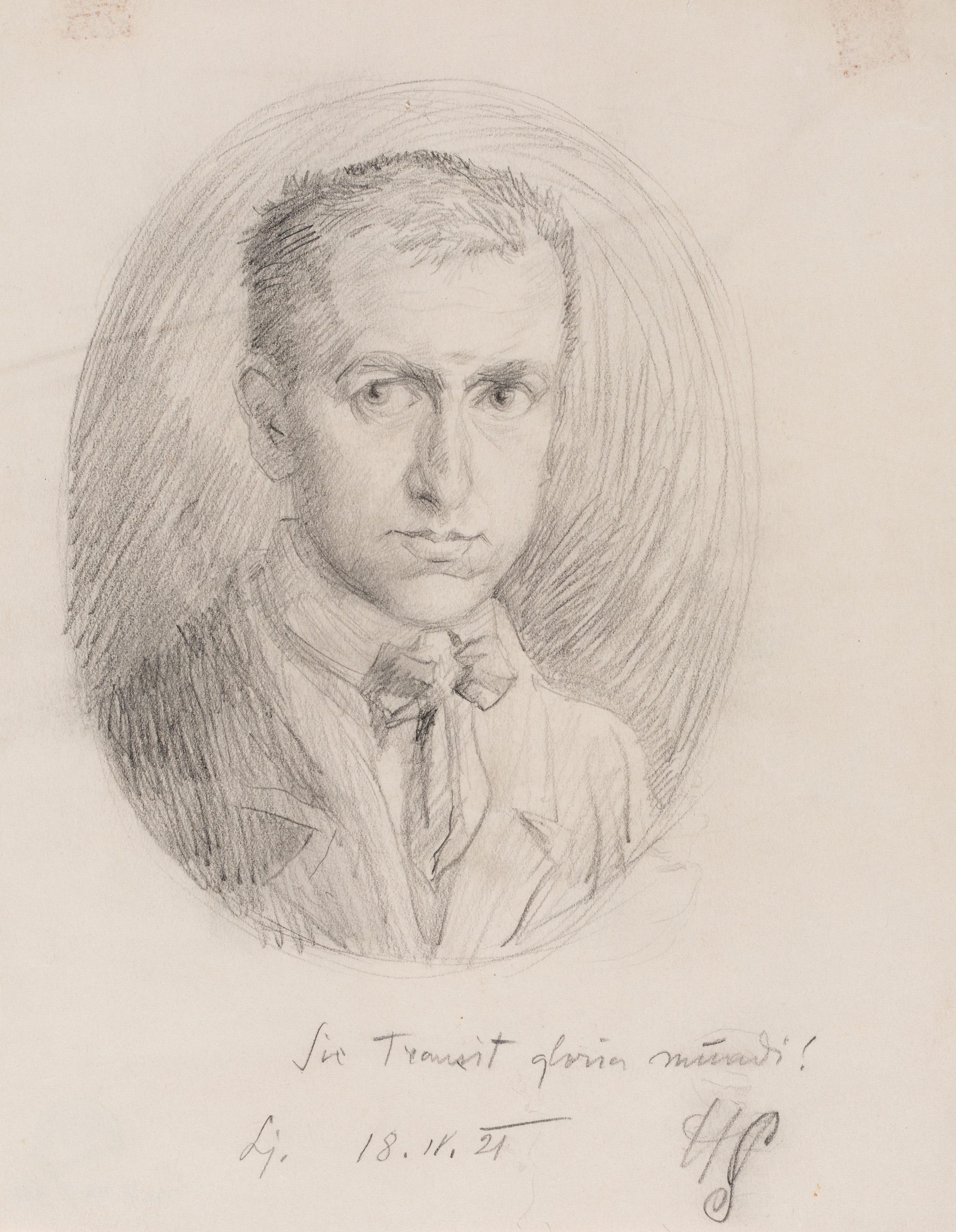

Fig. 4

Hinko Smrekar

Self-Portrait, 1921

National Gallery of Slovenia

In the autumn of 1921 he returned to Laßnitzhöhe, whence he reported that the prices had gone up, that his doctor was constantly imbibing nerve powders, and that it was no longer clear who needed treatment: him or the doctor. He therefore removed himself to the nearby Mariagrün sanatorium in Kroisbach, near Graz, but he was still not satisfied and reported that the prices were very high there too. Smrekar wrote to an unknown friend that he had doubts about the Austrian sanatoriums, which were “amusement parks for worn out profiteers”. He was thus thinking of going to a resort in Maribor, Rimske Toplice, Radgona or Bad Wörishofen, because he trusted German fastidiousness and seriousness Thus in 1922 we find him in the spa town of Bad Wörishofen, which was known for the water cure or hydrotherapy developed by Sebastian Kneipp.

Since his health failed to improve, he travelled to various locations around Slovenia in search of fresh air and a quiet life. He received invitations both from friends and from total strangers. In the latter case, these were art lovers who had read in the newspapers that the artist was in need of treatment and help. During his treatment, Smrekar turned to several institutions for help in paying off the debts he had accumulated as a result of his illness. He petitioned the Presidency of the Provincial Government for Slovenia, the Ministry of Education in Belgrade and the Town Hall of the State Capital in Ljubljana. He also received financial support from various banks, the Credit Institute for Commerce and Industry, and the painter Gvidon Birolla, a friend from his student days who had inherited the family lime works. Smrekar’s poor health compelled him to turn down several offers of employment, for example a post teaching drawing in the Architecture Department of the Faculty of Engineering in Ljubljana that was offered to him by the architects Ivan Vurnik and Jože Plečnik.

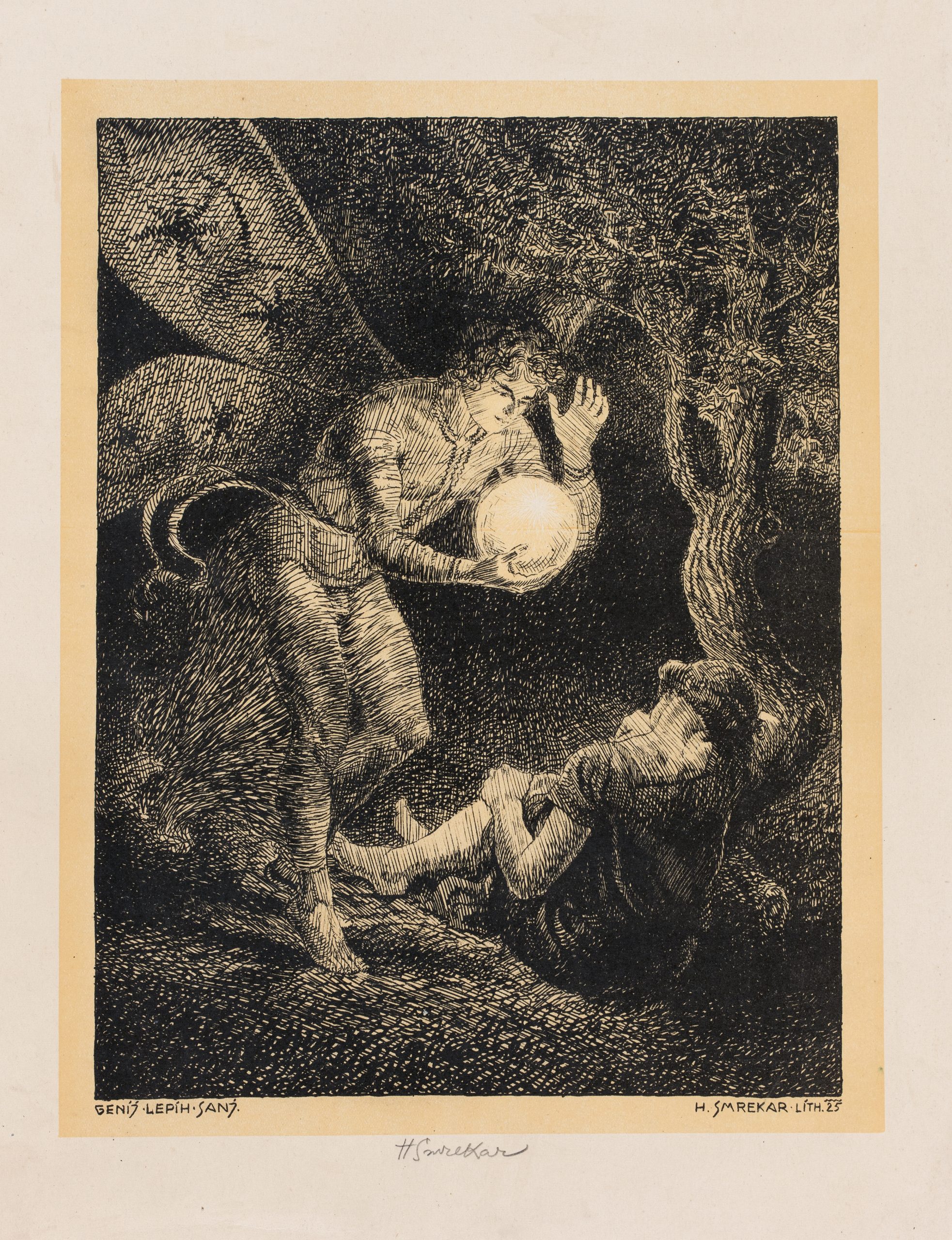

Fig. 6

Hinko Smrekar

Genius of Pleasant Dreams, 1925

private collection

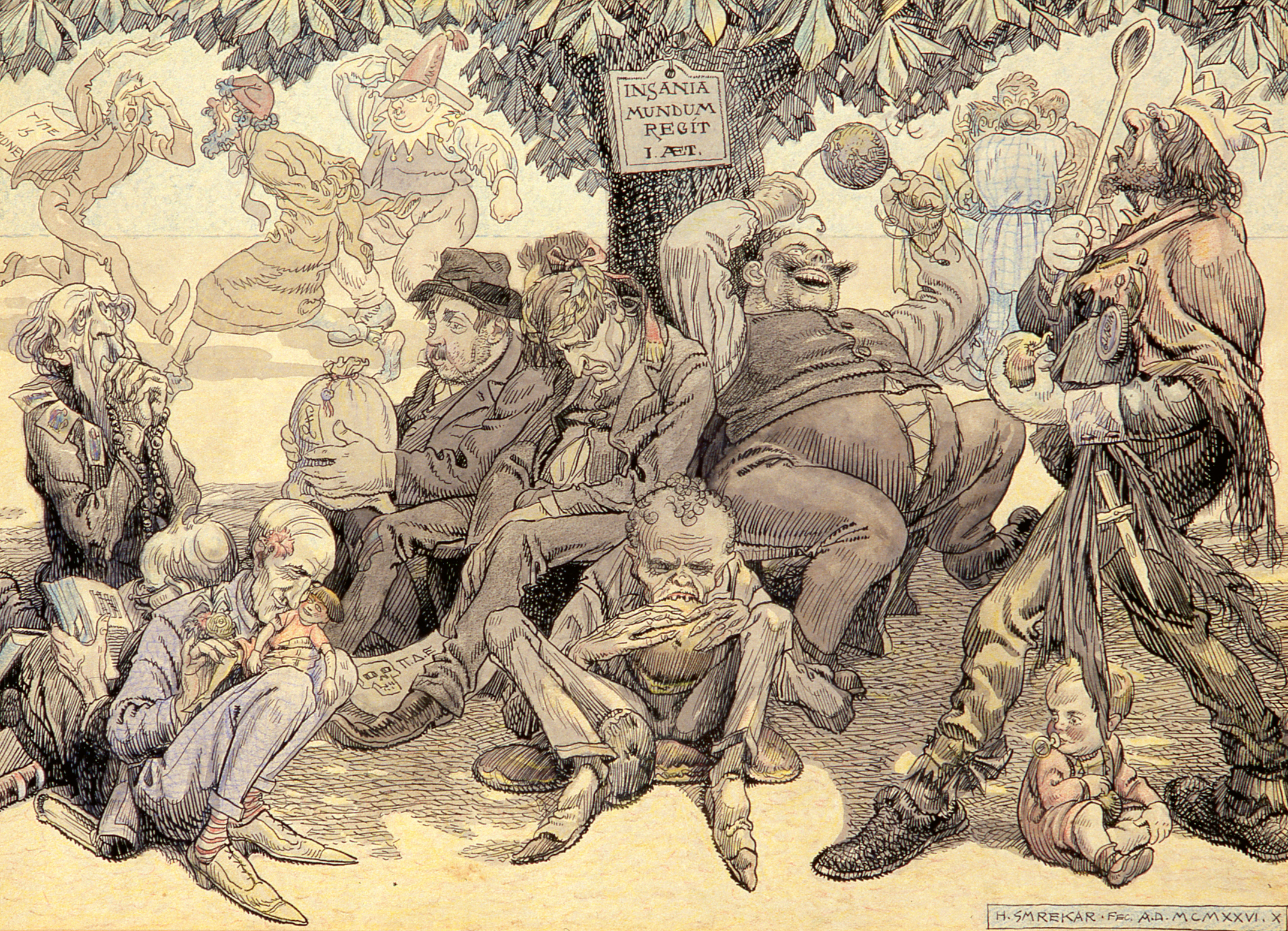

Fig. 7

Hinko Smrekar

Madness Rules the World, 1926

location unknown

The drawing depicts a group of strange characters under a leafy tree with the inscription “Insania mundum regit”. The scene is presumably set in the courtyard of an insane asylum, and shows a man biting his own belly, another dressed as a king with a wooden spoon and a fool’s crown, one holding a sack of money in his lap, another clutching a toy doll, a scholar studying a book, and among them Smrekar with a laurel wreath and a sheet of paper at his feet with a drawing of a skull and the letters “ΠΔΕ”. The characters are reminiscent of the vices Smrekar later interpreted in the cycle The Seven Deadly Sins, while the spirit of the scene brings to mind Francisco Goya’s similar scenes borne of the anxieties and fears following his nervous breakdown.

The entire period up to 1937 was marked by a constant struggle for survival and endless requests for loans or subsidies, while between 1932 and 1934 his chronic nervous condition once again left him unable to work. The public did not stand idly by, however, and helped him in any way they could, either offering advice or appealing to their contacts and acquaintances. Those who helped him included both ordinary citizens and important politicians. Fran Windischer, for example, helped Smrekar in requesting a deferment of debt payments and also obtained support for him from the so-called poverty fund of the Drava Banovina for the year 1934–1935.

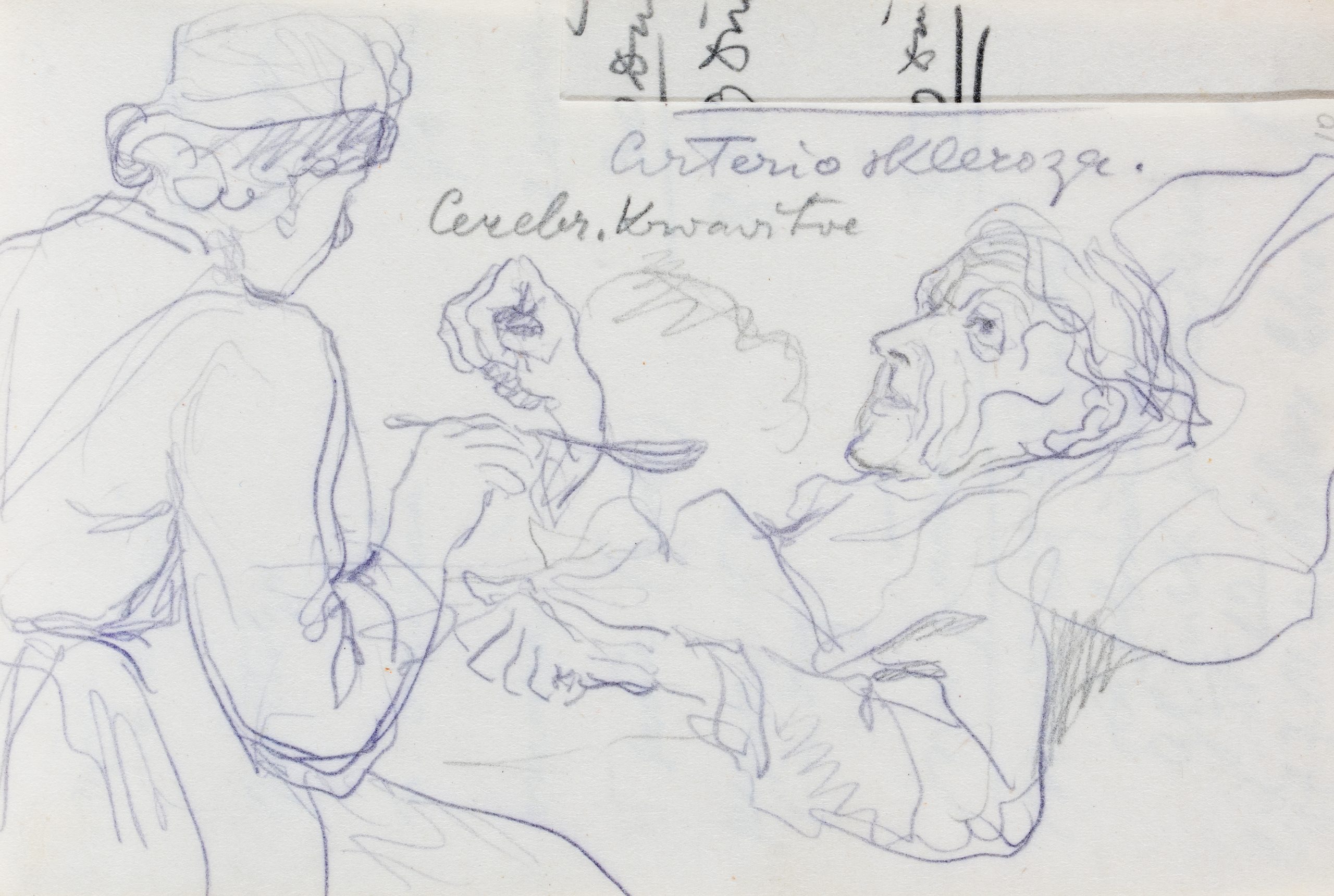

The sketchbook with drawings of mental patients from the Studenec hospital, where Smrekar is thought to have been treated again in 1937, is a true curiosity and treasure. No correspondence on this matter could be found, with the exception of Smrekar’s notes about his poor health, which was a constant in his life. The drawings give an accurate psychological insight into patients with various illnesses. They are executed in graphite and pared down to the essential elements – the eyes, facial expressions or posture.

Fig. 8

Hinko Smrekar

Drawings from the Studenec Asylum, Sketchbook, 1937

private collection

There is no evidence that Smrekar’s health improved significantly after 1937, but neither did he retreat into solitude. As though wishing to start afresh, he accepted commissions to provide illustrations for numerous satirical publications and books for adults and children and continued to record everyday events through social satires and caricatures. Sadly his creative momentum and oeuvre were interrupted by his violent death.

Select bibliography

Legacy of Fran Vesel, Hinko Smrekar, National and University Library, Manuscript Collection, Ljubljana

Hinko Smrekar, Henrik Smrekar, – črnovojnik, Ljubljana 1919

Franc Uršič, Hinko Smrekar. Za 25-letnico njegovega umetniškega delovanja, Slovenec, 56/287, 16. 12. 1928, p. 9

E[lko] Justin, Andersenove pravljice Hinka Smrekarja. Odlomek iz spominov na pokojnega prijatelja-umetnika, Tovariš, 7/16, 7. 6. 1951, p. 260

Stane Mikuž, Po razstavi Hinka Smrekarja, Ljudska pravica, 13/46, 15. 11. 1952, p. 10

Janez Nedog, Umetnik – do smrti zvest svojemu ljudstvu. Spomini na srečanja s Hinkom Smrekarjem v zadnjih letih njegovega življenja, Ljudska pravica, 13/42, 18. 10. 1952, p. 10–11

M. S., Strah pred porogom požene kroglo vanj, Delo, 20/267, 1. 10. 1978, p. 13

Author: dr. Alenka Simončič, 2022