Book Illustration

The transition from the nineteenth century to the twentieth was marked by enormous creativity both in literature and the arts. An extremely important position in the development of Slovenian culture was held by the merchant and publisher Lavoslav Schwentner (1865–1952), who moved from Brežice to Ljubljana in 1898 (Fig. 1). He was dubbed the “court publisher of Slovenian modernism” by virtue of his contribution to the establishment of the movement and accepted for publication a great number of thematically and ideologically controversial texts that were also commercially risky and which — owing to these considerations and the censorship exercised by the editorial and management boards of the existing publishing houses — would otherwise never have seen the light of day. Among other things he printed Erotika, a collection of poems by Ivan Cankar (1876–1918) after the first edition had ended up on the pyre. Anton Bonaventura Jeglič, then prince-bishop of Ljubljana, had in fact bought up all the copies he could get his hands on and had them burnt, on the grounds that this poetry was anti-Christian and immoral, with the result that of the thousands of copies printed, only three hundred found their way into readers’ hands.

Fig. 1

Hinko Smrekar

Publisher’s Device of Lavoslav Schwentner, (1914)

National Gallery of Slovenia

Schwentner devoted particular attention to the physical appearance of books. – at first the architect Ivan (John) Jager, then the Impressionist painters Matija Jama and Rihard Jakopič (1869–1943), and later the artists of the Vesna group (Maksim Gaspari, Gvidon Birolla, Ivan Vavpotič, etc.), who played a key role in introducing Art Nouveau elements to Slovene art and who were more versatile than the Impressionists. As well as painting in oils, they worked in the media of drawing and printmaking and, precisely because of their drawing skills, were in great demand as illustrators. (Fig. 2‒6)

Fig. 2

Ivan Jager (1871–1959)

Sketch for the cover of Oton Župančič’s poetry collection Čaša opojnosti, (1899)

The Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts

Shortly before Easter 1899, Schwentner published an edition of Oton Župančič’s first poetry collection Čaša opojnosti (The goblet of intoxication) that attracted attention for its unusual appearance. The book was of a more elongated format than usual and each poem began on its own page, while the cover was adorned with a drawing of a man and a woman in saintly garb.

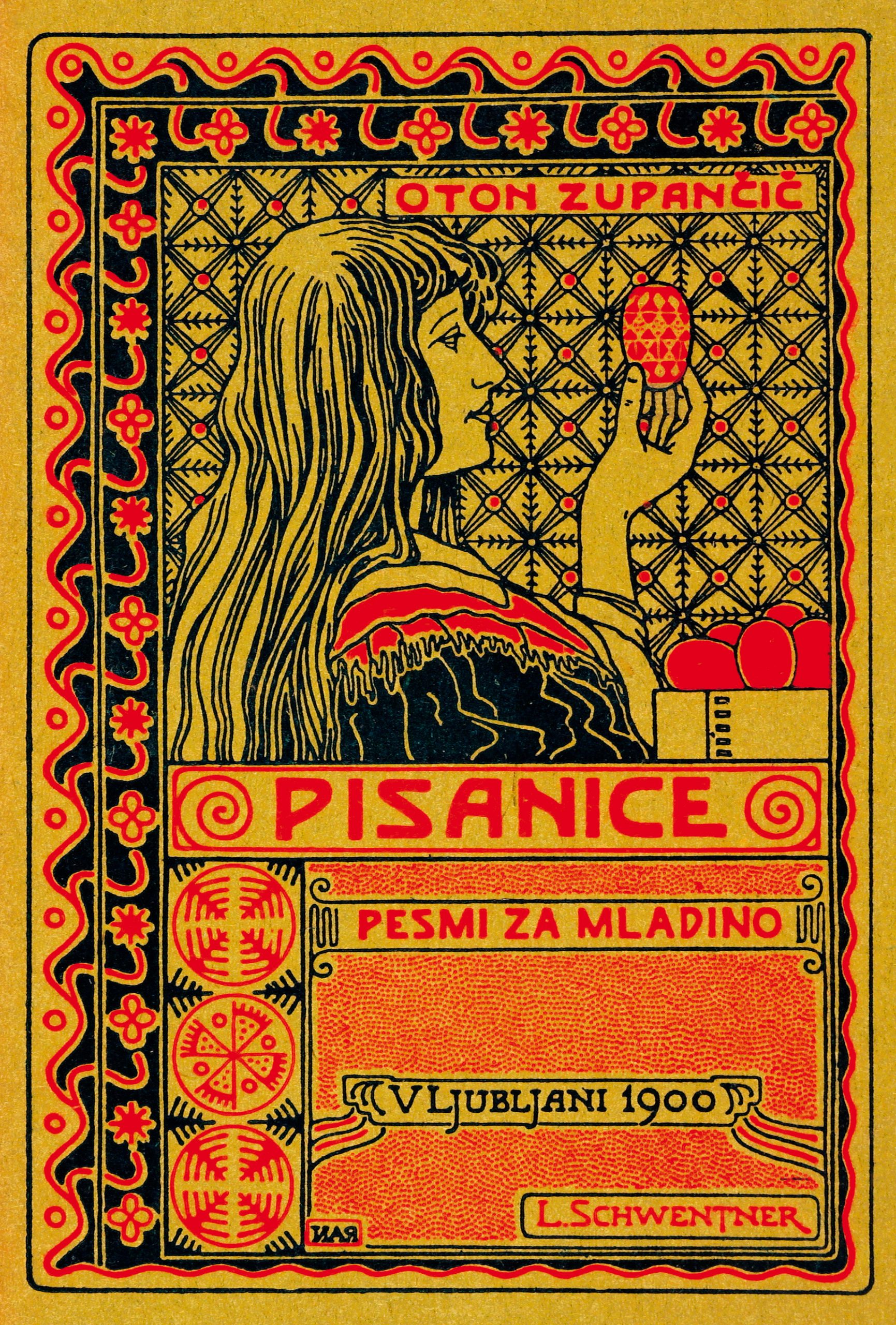

Fig. 3

Ivan Jager (1871–1959)

Sketch for the cover of Oton Župančič’s poetry collection Pisanice, (1900)

The Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts

The cover of this collection of poems for young people is decorated with patterns from painted Easter eggs, known in Slovenia as pisanice.

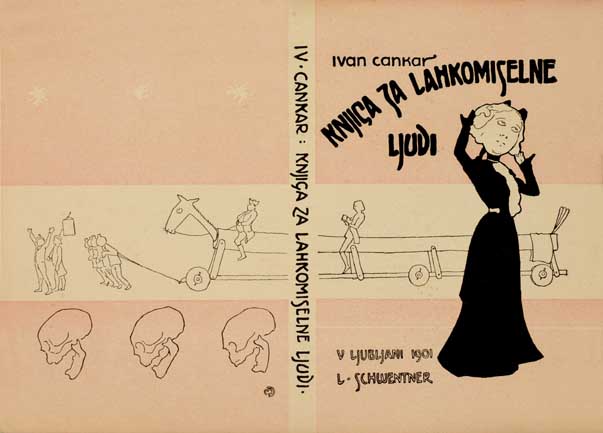

Fig. 4

Matija Jama (1872−1947)

Cover of Ivan Cankar’s short story collection Knjiga za lahkomiselne ljudi, 1901 National Gallery of Slovenia

Cankar’s Knjiga za lahkomiselne ljudi (Book for frivolous people) was the first book in Slovenia to have a cover illustration that extended across the front cover and continued on the back.

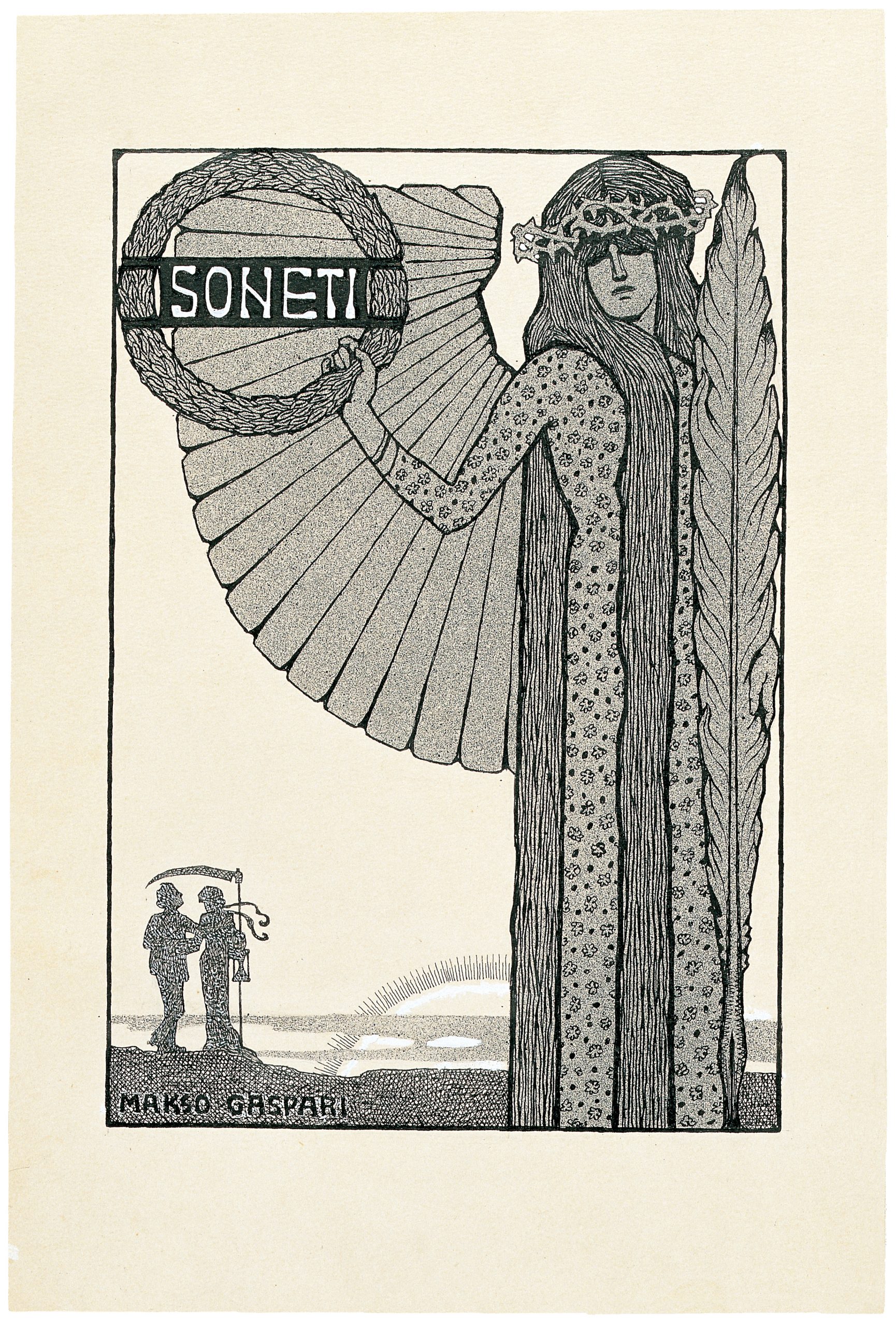

Fig. 5

Maksim Gaspari (1883‒1980)

Sketch for Sonnets title page of Dragotin Kette’s poetry collection Poezije, (1907)

National Gallery of Slovenia

Gaspari’s illustrations for the second edition of Poezije, a collection of poems by Dragotin Kette published in 1907, belong at the pinnacle of illustration in Slovenia. Gaspari drew several full-page illustrations and vignettes in an Art Nouveau spirit, featuring supernaturally beautiful women in the embrace of Death. The harp, the hourglass, the scythe, the ethereal female images and dark-shrouded figures are true symbols of turn-of-the-century love poetry.

Fig. 6

Maksim Gaspari (1883‒1980)

Sketch for title page in Dragotin Kette’s poetry collection Poezije, (1907) National Gallery of Slovenia

Kette’s Poezije collection also includes rhymes and fables for children. For this chapter Gaspari drew a full-page illustration showing the princess of children’s poetry living high in a treetop with a wonderful view over Lake Bled with its island and little church.

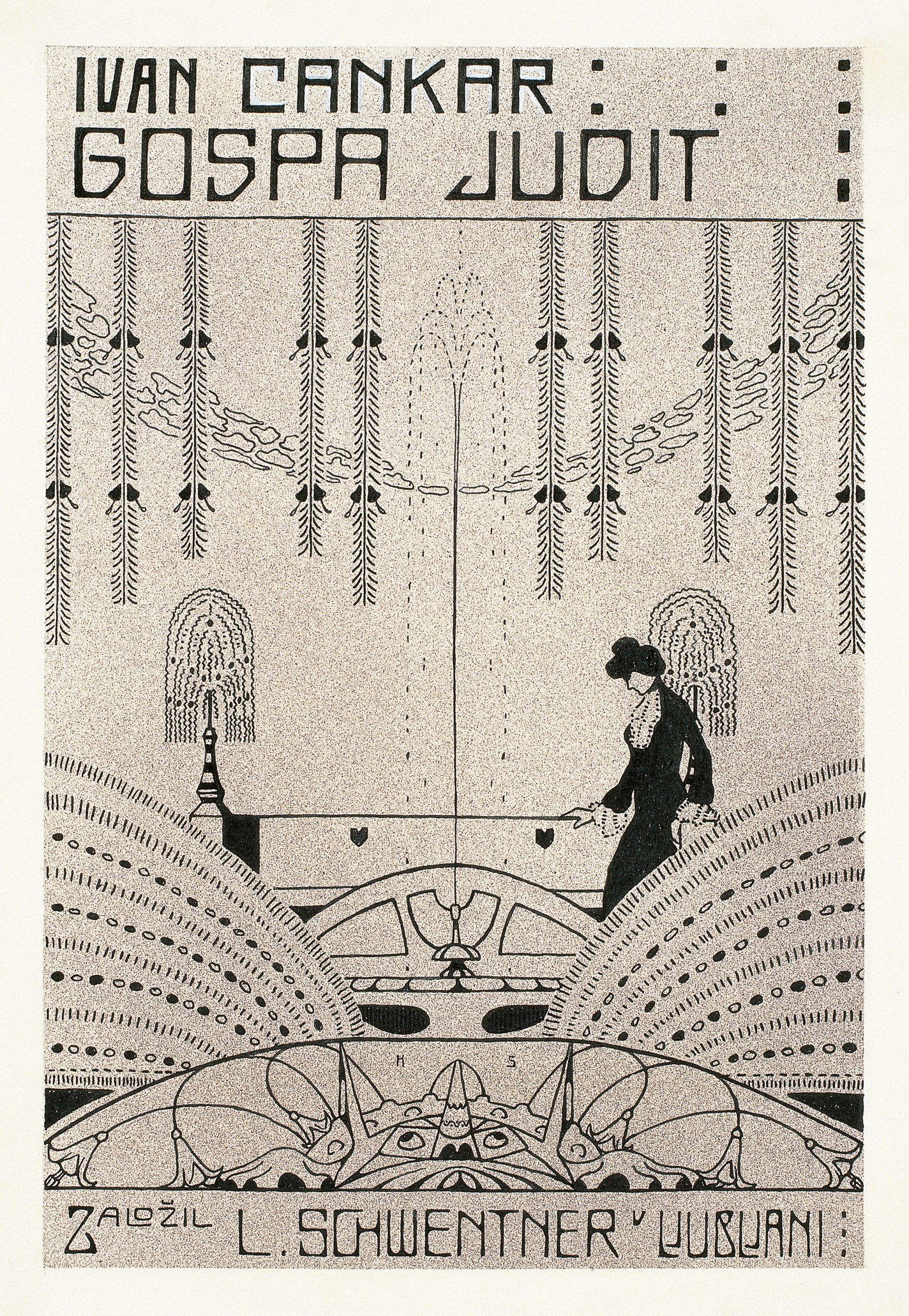

The draft for Madam Judit is one of Smrekar’s earliest surviving works. It emanates the ideals of the Vienna Secession and links directly to the circle around Gustav Klimt. In a drawing that reflects sensitivity and precise draughtsmanship, he has placed in a stylised landscape the fashionable silhouette of a lady strolling past a fountain in a park, to which she has retreated from a grey Viennese suburb Beginning with the cover for Gospa Judit, went on to illustrate several of Cankar’s books. He drew several drafts of individual jackets and internal decorative apparatus. “There would have been even more, but the principal obstacle was that the publisher had legitimate financial concerns. Despite this, he took great pains to ensure that the books were solidly and attractively made and decorated. Time and again, I endured Schwentner’s four sorrowful-yet-careful inspections: the first time he would roll his eyes to the sky, the second time he would avert his gaze, the third time he would look at the floor and the fourth time he would look me in the eye,” remembered Smrekar.

Fig. 7

Hinko Smrekar

Draft of the front cover page for the book Gospa Judit (Madam Judith) by Ivan Cankar, 1904

National Gallery of Slovenia

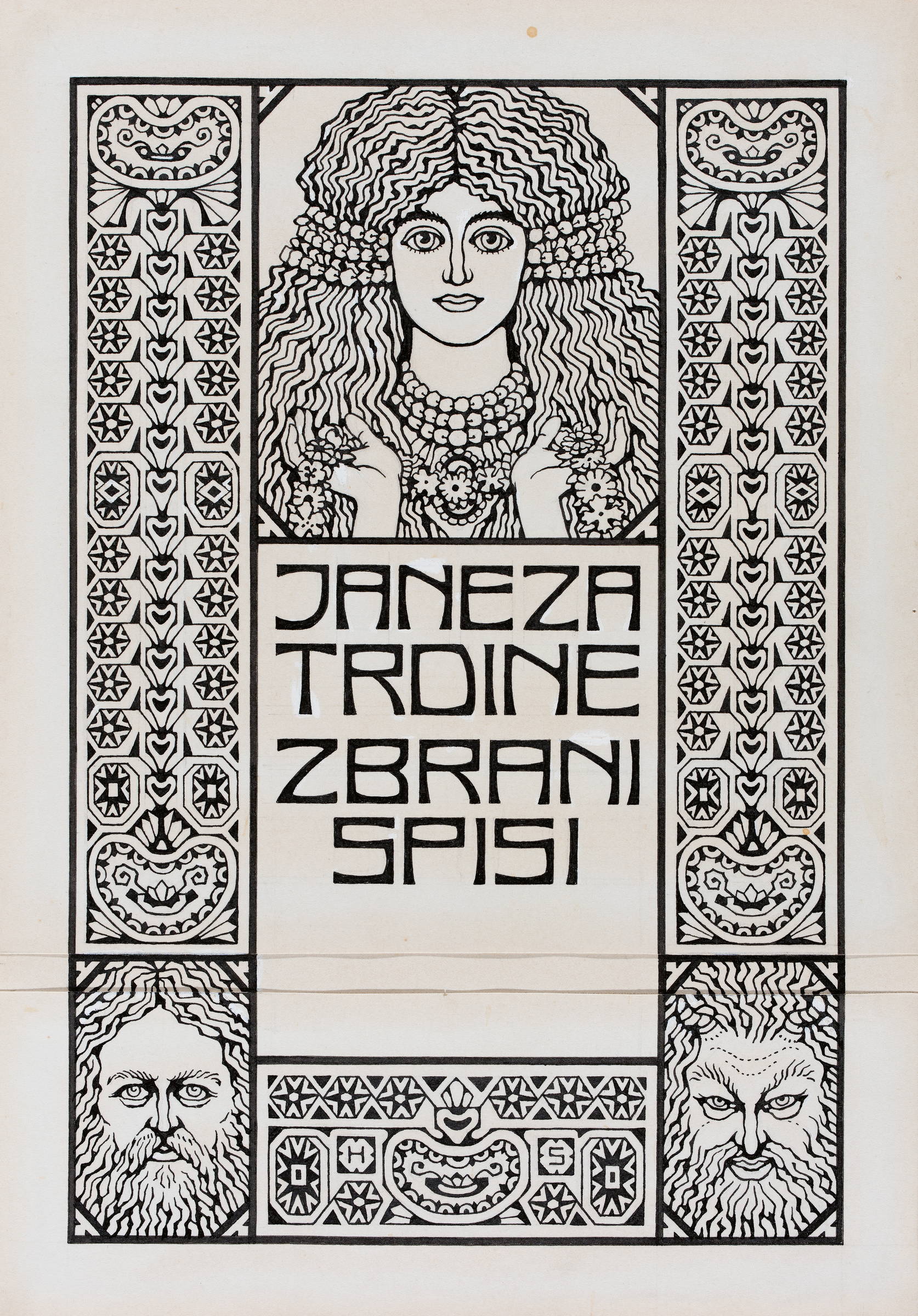

Smrekar’s association with Cankar, seven years his senior, had an increasing influence on the young artist. It was under Cankar’s influence that Smrekar began to develop a sharp critical tone, which he then continued independently in his caricatures. Smrekar did not only find a personal friend in Ivan Cankar. Above all, he saw him as a kindred spirit. At the same time, a new creative force was born — art without lies, fine words and hypocrisy and with clear ideas about human values. The essence of their works is not so much satire as a profound confession and a calling to account of society. The revolt against the bourgeois limitations and conventionality that stifled people’s lives and, above all, against the attitude of the ruling classes towards art and the artist — the latter superfluous to his nation and fated to die young – was a common thread throughout Smrekar’s life and also linked him closely to Cankar. As well as Cankar’s books, Smrekar illustrated several others in this period. In 1909 he drew the cover for Obsojenci (The Condemned), a collection of short stories by Vladimir Levstik, accepted an invitation from the Serbian Royal Academy to provide illustrations for a collection of Serbian heroic folk poems (Srpske narodne junačke pesme) (1913), the front cover page of the Collected Essays of Janez Trdina (1914) and saw Smrekar complete illustrations for a work entitled Literarna pratika za 1914. leto (Literary Almanac for 1914), which is considered to be his most extensive illustration project.

Fig. 8

Hinko Smrekar

Draft of the cover for the book Zbrani spisi (Collected Essays) by Janez Trdina, (1914)

National Gallery of Slovenia

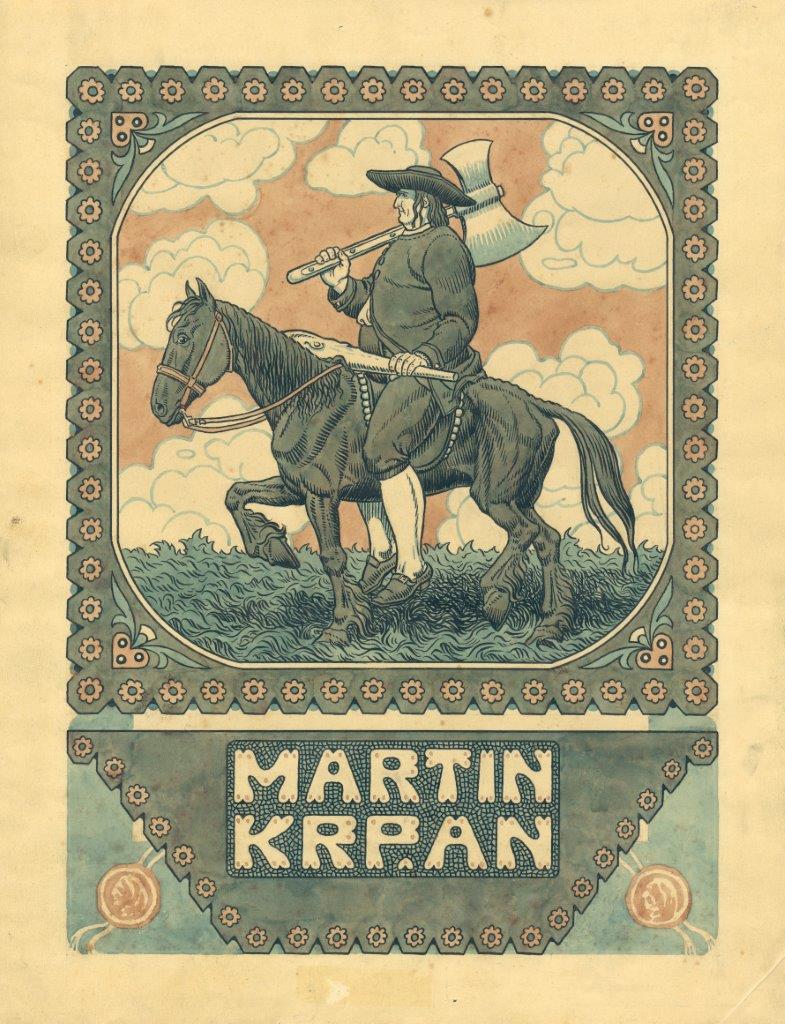

In 1917 Smrekar received a commission to illustrate Fran Levstik’s story Martin Krpan. In addition to the coloured cover depicting Martin Krpan on his mare, Smrekar produced twelve pen-and-ink drawings.The illustrations belong at the very pinnacle of Slovene illustration.. They appeal equally to children and adults and are distinguished by their narrative power, their immersion in the Baroque period with its courtly costumes and backdrops, and the characters’ psychological depth: the bloodthirsty nature of the exotic Brdavs, and above all the arrogance and contempt of the nobles whom Krpan encounters at the court. The contrast between Krpan’s natural fierceness and the Emperor’s effeminate appearance imbues the former with symbolic meaning. Martin Krpan was no ordinary provincial man. He was of giant stature, immensely strong and headstrong as his smuggler’s way of life had shaped him differently from the worn out, scrawny peasants — and Smrekar portrayed him as such.The art historian Stane Mikuž wrote: “The grandeur of Levstik’s text attracted the painter with its suggestiveness, embraced him with its homeliness and brought him down to earth. Never before and never since has Smrekar been so constructive and comprehensive as in these superb illustrations. Here, the painter’s natural inclination for caustic satire submits itself to the supremely mischievous peasant’s sense of humour.”

Fig. 9

Hinko Smrekar

The cover and illustration for the story Martin Krpan z Vrha (Martin Krpan from Vrh) by Fran Levstik)

Miran Jarc Library, Novo mesto

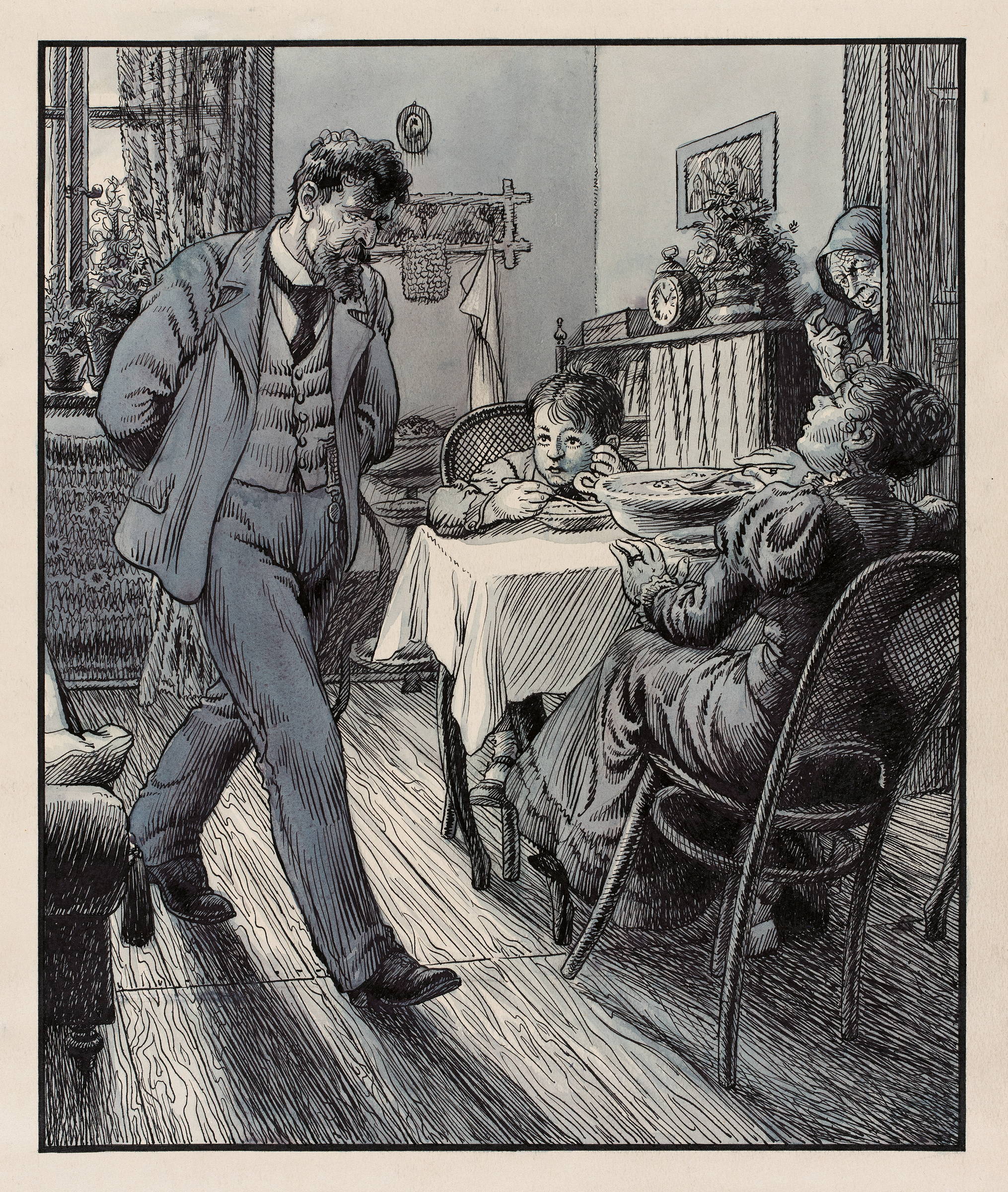

Between 1918‒1942 Smrekar illustrated innumerable cover pages of magazines and several poems and books by Slovenian and foreign authors. Between 1935–1937 he illustrated Fran Milčinski’s book Ptički brez gnezda (Nest-Less Little Birds), in which the author draws attention to uncaring parents and the neglect of children. Fran Milčinski (1867–1932) was a youth writer, story-teller and playwright, who was considered the best Slovenian humourist of his time. Milčinski and Smrekar both liked to mock everything that went against their social consciousness and common sense. They often switched from humour to satire, and both were astute observers and judges of human morals and social deficiencies. The original drawings for Ptički brez gnezda, where Milčinski touched upon the issue of disadvantaged youth, have fortuitously survived.

Fig. 10

Hinko Smrekar

Mr Jeraj Complaining about Lunch, Jera the Cook calls Little Milan out of His Room, illustration for the book Fran Milčinski, Ptički brez gnezda. Povest (Nest-Less Little Birds. A Story), (1935‒1937)

National Gallery of Slovenia

Smrekar’s sensitive nature, gift for observation, powerful memory, compositional fantasy, relaxed drawing style and technical skills – these are the qualities that distinguish his illustrations for children’s books such as Sto basni za otroke (1936), Beli bratec by Marija Jezernik (1937) and Grajski vrabec by Davorin Ravljen (1938).

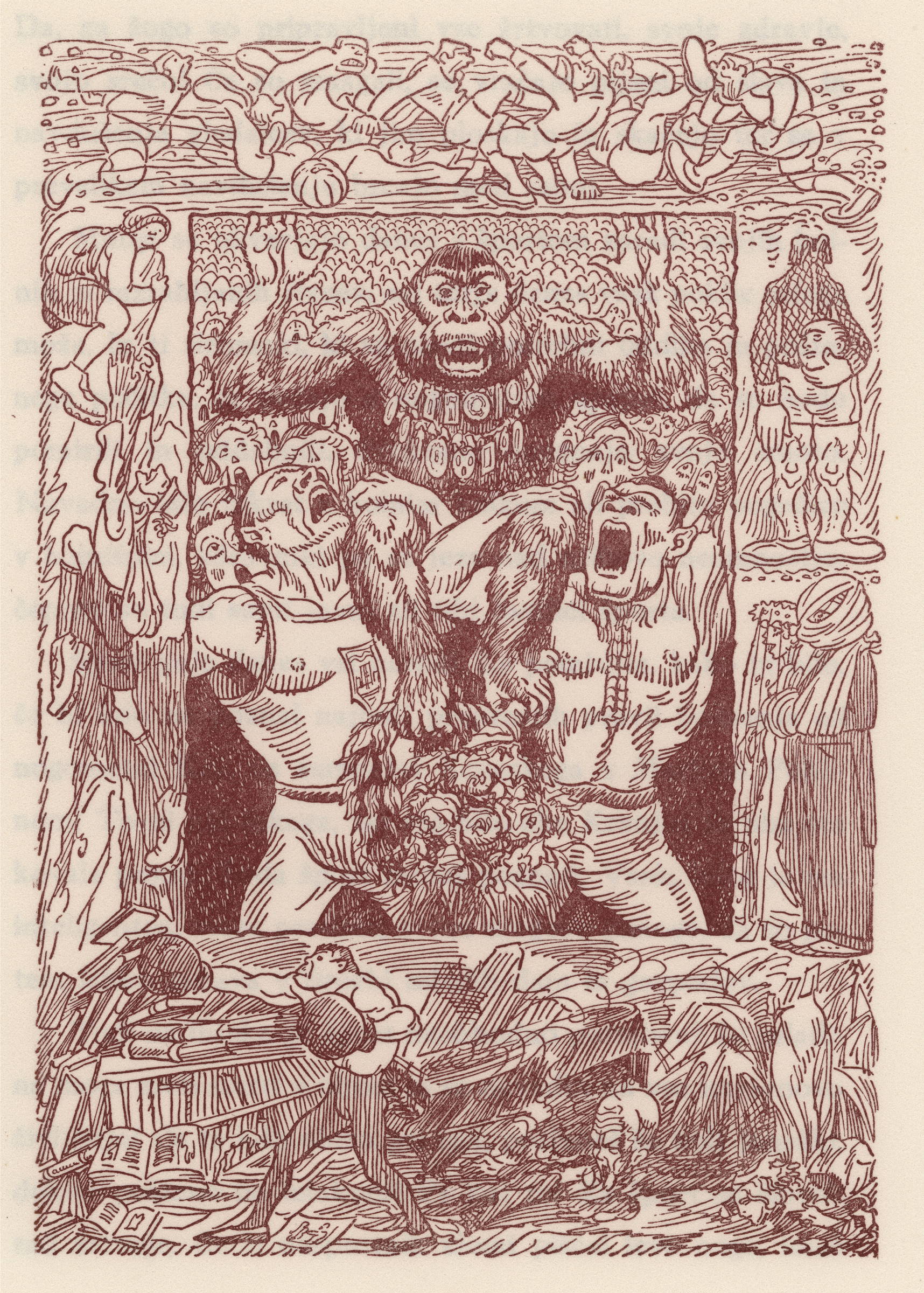

Smrekar’s collaboration with Gustav Strniša (1887—1970) on the illustrations for Satire (Satires, 1938, cat. nos. 1399—1419) was a meeting of kindred spirits. Probably not since illustrating Cankar’s books had he encountered such an insightful text that was also very close to his views. In Satire, Strniša boldly ridiculed and exposed the vices and indulgences of social and cultural life. For the chapter “Morilec” (Killer), Smrekar drew a critic in the studio of Maksim Gaspari, who is seen in the background in a contorted pose, as he can no longer listen to unfounded criticism, while the chapter “Pretirani športi” (Excessive Sports) (Fig. 11) is accompanied by a drawing of King Kong (the eponymous film was released in 1933) showing off his muscles, which are more important than any knowledge. The title character of the chapter “Zavist” (Envy) is carried on a stretcher in a carnival procession; her face is even more hideous than those depicted in the cycle of vices, and under her cloak she shelters a pack of rats.

Fig. 11

Hinko Smrekar

Overdoing Sports, illustration for the book Gustav Strniša, Satire (Satires), (1938)

location unknown

In 1940 Smrekar self-published (as the publisher “Sila”) and illustrated a collection of seven of Andersen’s fairy tales (cat. nos. 1622–1645). The book could be ordered with prepayment, and all copies were hand-signed by the “author– illustrator–publisher”. Despite illness, Smrekar produced the drawings in a few weeks. The collection included the fairy tale Hudobni knez (The Wicked Prince), with which Smrekar wanted to draw attention to the horrors of war and Fascist violence. The tale of Hudobni knez begins thus: “There lived once upon a time a wicked prince whose heart and mind were set upon conquering all the countries of the world and on frightening the people; he devastated their countries with fire and sword, and his soldiers trod down the crops in the fields and destroyed the peasants’ huts by fire, so that the flames licked the green leaves off the branches, and the fruit hung dried up on the singed black trees.” Smrekar and the translator of the fairy tales, Mirko Košir (1905–1951), wanted to warn readers of the imminent dangers and awaken their consciences, choosing a seemingly innocent tale to avoid censorship. At the end of World War II, Košir wrote how right they were to choose this story, since the prince’s plans were identical to those of Hitler, who said just before attacking Poland: “The citizens of Western Europe must tremble with horror.” (Fig. 12)

Fig. 12

Hinko Smrekar

Gun Bullets Bouncing from an Angel’s Feathers, illustration for the fairy-tale The Wicked Prince from the book of Andersen’s fairy-tales, (1940)

location unknown

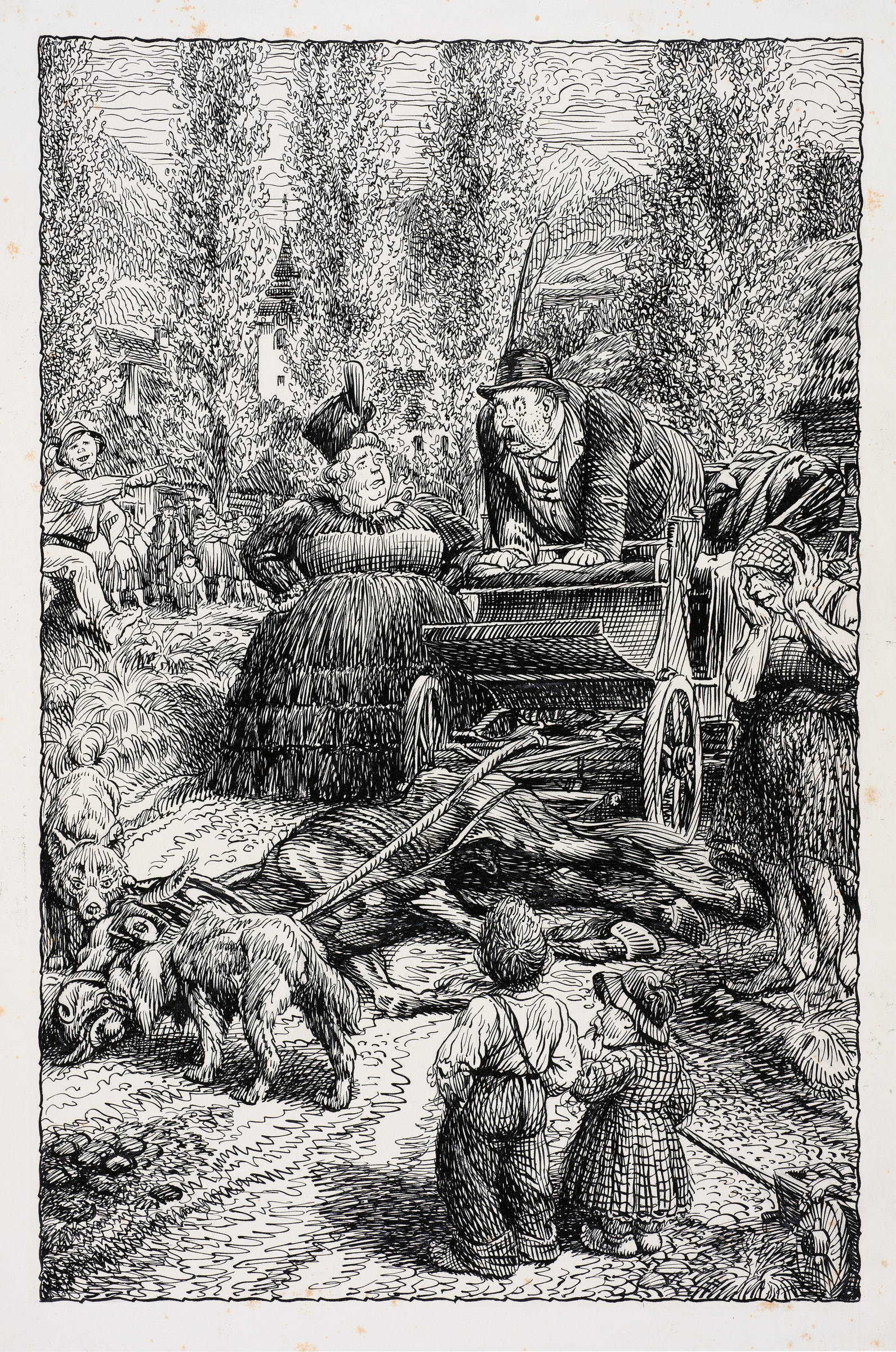

The last book that Smrekar illustrated was Zaplankarji (Hillbillies, 1941, cat. nos. 1712–1728), a collection of humorous stories by the priest and writer Joža Vovk (1911–1957). The stories are set in the village of Zaplanke, the name itself (“fenced off with planks”) suggesting that the author is mocking its inhabitants, their stupidity and narrow-mindedness, although he also attributes a unique ingenuity to them. Smrekar was once again on familiar ground, and produced teeming illustrations, group scenes with crowds of squashed and intertwined figures. They demand close and repeated viewing, as Smrekar’s best jokes are usually to be found in the details. (Fig. 13)

Fig. 13

Hinko Smrekar

On How the Hillbillies Bought a Horse, illustrations for the collection of humoresque tales Zaplankarji (Hillbillies) by Joža Vovk, (1941)

private collection

Author: dr. Alenka Simončič, 2022