Stylistic and Iconographic Comparisons

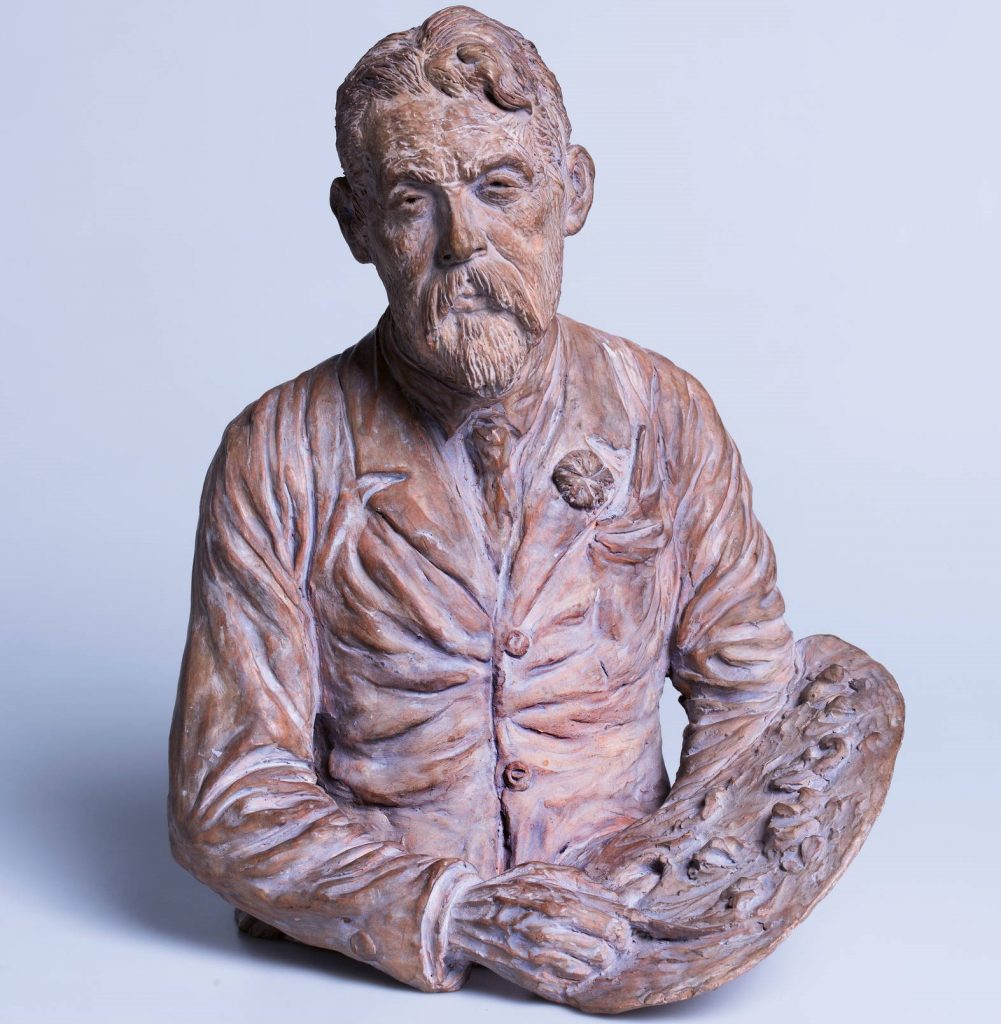

With few exceptions, his extensive oeuvre contains no preparatory sketches, while in the case of portraits he often used photographs as aids. In the majority of cases there is a visible underdrawing in graphite, which Smrekar then covered and finished with Indian ink. His speciality was pen-and-ink drawing – washed, watercoloured or combined with pastels; his prints – woodcuts, etchings aquatints – place him among the finest printmakers of the era. In later years he also tried his hand at oil painting and, in around 1940, sculpture (like the portrait of the Slovenian Impressionist Ivan Grohar on the left).

He himself wrote: “Where did I train as a printmaker and painter? Least of all on school benches and more everywhere else; more in my sleep than awake at school. Even as a child I was stubborn and resisted all dictates as much as I could. Vienna, Munich — what do they mean? Every poor little tree in my homeland moved my heart more profoundly and told me more…”

Smrekar is one of those artists who places experts in a quandary because he is too capable or, if your prefer, too stubborn to let himself be harnessed by the narrow fetters of the latest fashion dictated by Paris or Berlin.

The painter Saša Šantel (1883‒1945) on the occasion of Smrekar’s fiftieth birthday

A conscientious search for the impulses that may have influenced the young Smrekar, thus produces few results: we find few works of art that could have made such an impression on him as to lead him to copy them.

Smrekar wrote that at the age of two he experienced a tremendous spiritual commotion, something that would remain with him for the rest of his life, as vivid as though it had happened yesterday. The cause of his agitation was the interior of the Church of the Annunciation, the Franciscan church, which from that moment on became his personal paradise. Every time he passed the church with his parents, he would scream and stamp his feet, so they had no choice but to go in. His mother would have to pick him up, to enable him to see better. The chief attraction was The Transfiguration of Christ by Matevž Langus, a painter of the Biedermeier period. The scene is copied from the last painting by Raphael, which Vasari described as the Italian Renaissance master’s “most beautiful and most divine work”. The composition is considered to anticipate the Baroque and was admired for centuries, including by Goethe, who said of it: “The two are one: below, suffering and need; above, effective power, succour. Each bearing on the other, both interacting with one another.« As Smrekar himself put it: “I had to be forcibly dragged away from there. It still draws me powerfully today — the mystery of that concavity.” At the age of four he experienced another spiritual commotion: among the toys left behind by his playmate Rici, who had just died, he found some printed drawing templates and a number of copies made using them that had apparently been drawn by Rici’s mother. From that moment on he drew whenever he could. He soon found an almanac, an old calendar, a dream book and a fragment of the caricatures of Wilhelm Busch, which became his art gallery and academy all in one.

On 28 September 1904, having abandoned his study of the law in Vienna, he enrolled in a drawing course at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts aimed at prospective teachers of freehand drawing. The course was run by the renowned art teacher Anton von Kenner (1871–1951). Smrekar attended lessons in anatomy and technical drawing, until financial difficulties forced him to quit after one year.

In Vienna he joined the group of young artists from Slovenia and Croatia who formed the Vesna art society or club.. They were young men, dreamers and visionaries, frequently oversensitive, unhappy in love and thwarted in society. They wanted to create something original but directed their efforts towards art that appealed to ordinary Slovenians. The members of the Vesna group were influenced in particular by the progressive artistic movement known as the Vienna Secession and its official publication Ver Sacrum — Organ der Vereinigung Bildender Kunstler Osterreichs. They were also influenced by the group of young German artists gathered round the Munich-based magazine Jugend. Magazines and journals were an important source of information about new artistic styles and technical advances in printmaking techniques such as woodcut, etching, aquatint and colour lithography. They were a treasury of ideas for individual iconographic motifs and compositional solutions and served as pattern books from which they took what they needed, or whatever suited their spiritual disposition.

Stylistic similarities and characters of similar type are also to be found in the magazines Jugend, Meggendorfer Blatter and, above all, Simplicissimus, Die Muskete, Neue Gluhlichter and Kikeriki!136 — for example in the drawings of Erich Wilke (the image of a priest), Victor Schramm, Heinrich Kley, Max Feldbauer, Adolf Hofer, Angelo Jank, Adolf Münzer, Paul Rieth, Albert Weisgerber and Heinrich Zille, among others.

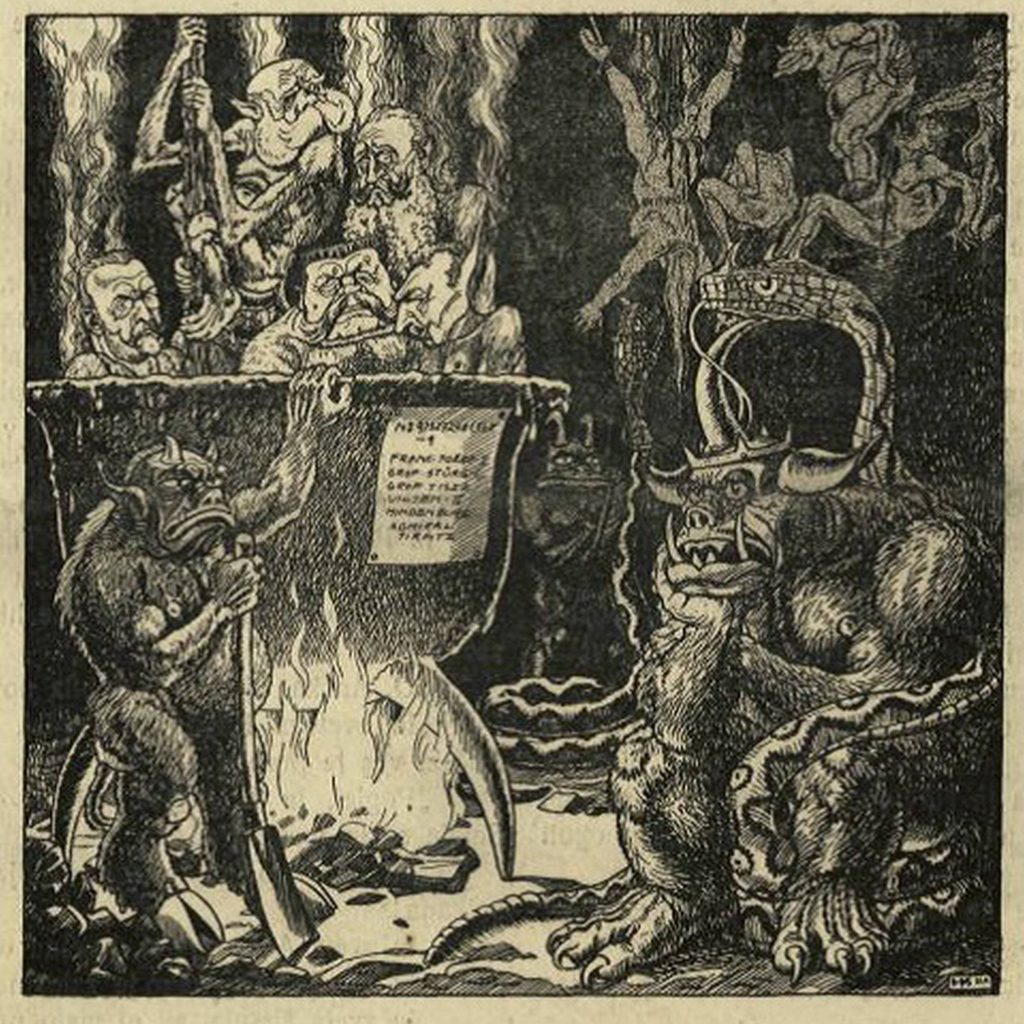

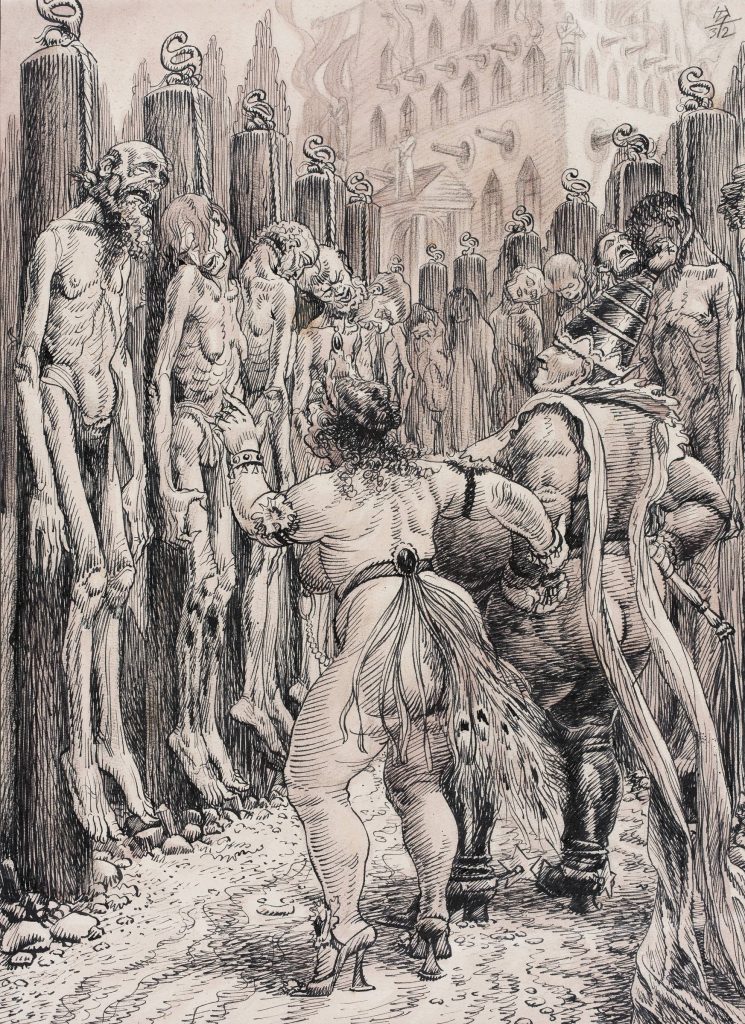

Smrekar likely borrowed the idea for his hell scene from a satirical illustration by Julius Diez in the magazine Jugend, although he enhanced the scene considerably. The denizens of Hell are regular guests in Smrekar’s drawings. They are so lifelike and realistic that it is as though Smrekar has summoned his best friends from an imaginary world to pose for him. These apparitions with accentuated human features are at once fascinating and frightening, because they are so true to life.

For the December issue of Kurent, Smrekar contributed the caricature Terrible Embarrassment, showing a crowded cauldron containing Emperor Franz Joseph, Austrian Prime Minister Karl von Stürgkh, Hungarian Prime Minister István Tisz, German Emperor Wilhelm II, Marshal von Hindenburg and Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz. They are being boiled alive by Satan, who is complaining about the headache of thinking how to reward them for their merits. Smrekar likely borrowed the idea from a satirical illustration by Julius Diez in the magazine Jugend, although he enhanced the scene considerably.

In terms of their lifelike quality, Smrekar’s fantastic scenes are comparable to those created by leading English illustrators such as Frank Cheyne Papé (1878—1972) and Arthur Rackham (1867—1939).

Smrekar’s boundless imagination is also evident in the various hybrid creatures that led contemporary critics to link him to the painter Hieronymous Bosch (1450–1516). They first appear in large numbers in the drawing Delirium (1913), and then in the drawings Man in a Magic Circle (1915) and The Land of Cockaigne (1919). He was also very fond of including them in drawings of witches rising up on their broomsticks into the sky, or in works of serious political satire. Given the large number of figures in The Land of Cockaigne, we can also link Smrekar’s work to the genre scenes of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, where the scene is filled with countless small figures that are unconnected to each other, with individuals or small groups of figures engaged in various activities and paying no heed to anyone else.

Hinko Smrekar

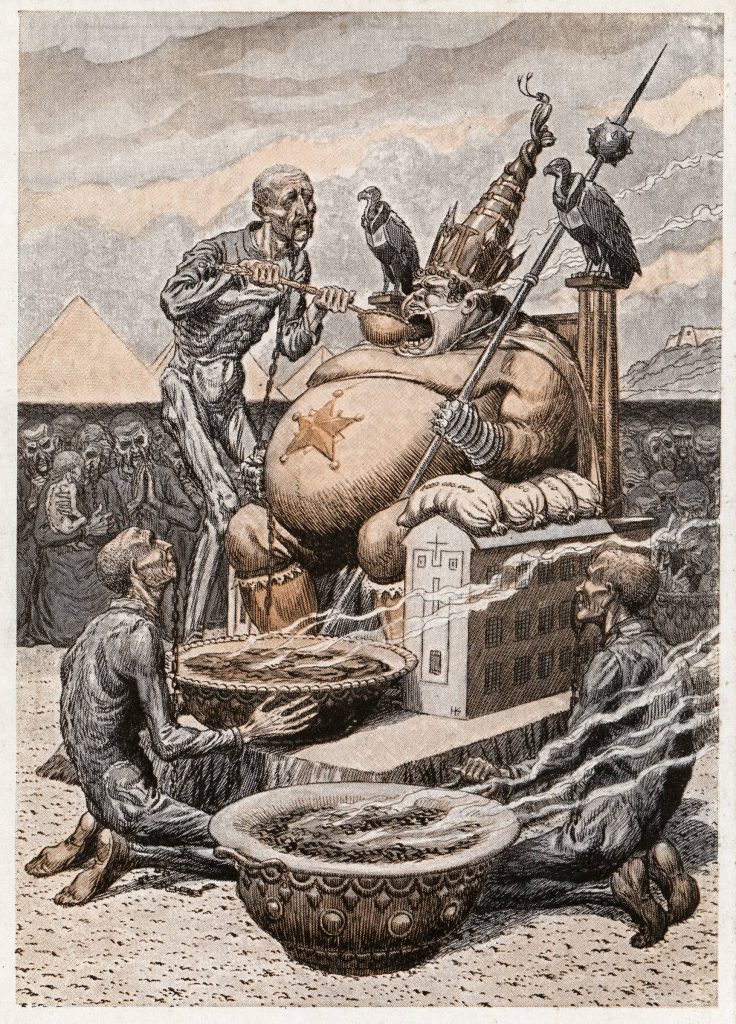

The Land of Cockaigne, (1919)

National Gallery of Slovenia

The titles of works of art such as Golden Age, Land of Dreams, Paradise Lost, New Life or The Land of Milk and Honey indicate a yearning for something lost and unattainable, and were common in the last years of the nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth. Cockaigne, also known as the Land of Milk and Honey, is the promised land where all can enter but Evil. The picture shows a lawn in front of a church that is filled with all manner of phenomena, creatures and curiosities, all serving to distract the attention of Evil. In this drawing we find everything we have already encountered in Smrekar’s work up to this point, and more besides. The trees are crosses between domestic fruit trees and palms, the animals come from every continent, as well as from fables and the bestiaries of medieval manuscripts, people of every age and gender are dressed in clown costumes — they dance, embrace and kiss and give themselves up to immense quantities of food and drink of every kind. The fat man in the foreground is a conventional personification of Capital.

Hinko Smrekar

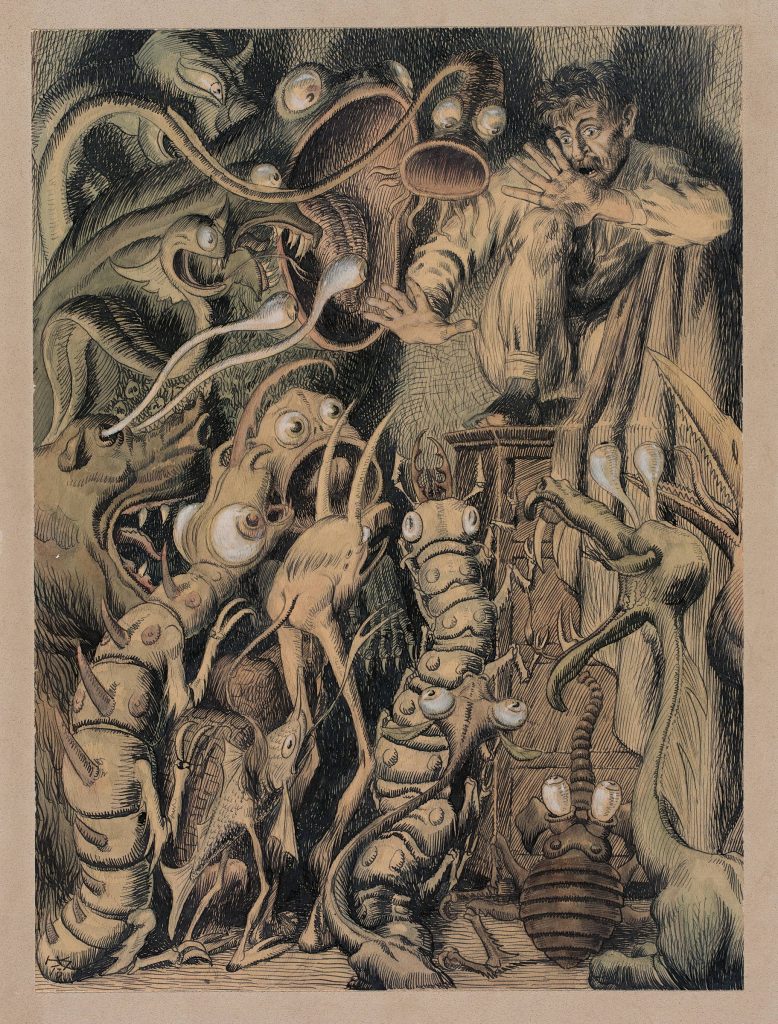

Delirium, (1913)

National Gallery of Slovenia

The origin of Delirium was recorded by the printmaker, writer and artist Elo Justin, who described Smrekar’s habit of immediately drawing the things that piqued his interest. Thus when the artist Ferdo Vesel introduced him to the fantastic illustrations of the Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch (1450–1516), he was instantly inspired to draw Delirium, also known as Fears. He drew a delirious man crouched in his underwear on top of a cupboard and trembling with the fear at the sight of a multitude of monstrous hybrids, including crosses of beetles, caterpillars, centipedes, fish, sea monsters, and so on. In short, all the creatures from Bosch’s pandemonium.

The members of the Vesna group admired the same artists: Gustav Klimt, Giovanni Segantini, Alfred Kubin, Arnold Böcklin, Richard Klingen, Franz von Stuck, etc. As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth, relations between the German and Slavic communities began to deteriorate. In order to distance themselves from German models and emancipate themselves in the field of the fine arts, they looked to Slavic artists — Russians, Poles and Czechs — as models instead. The latter were characterised by monumental nineteenth-century works featuring scenes from national history that drew attention to those values held to be fundamental for the maintenance of identity and consolidation of the nation. They shared with them the idea of awakening national awareness, of calling to mind everything homely and domestic, in order to feel connected with past centuries and so the people would not forget who they were and where they came from. The ideal of the members of the Vesna group was the Czech painter Joža Uprka (1861–1940), who painted scenes of peasant life in his home village in Southern Moravia.

The Vesna members also found a confirmation in national ideals with the Polish painters Władysław Jarocki (1879–1965) and Józef Pankiewicz (1866–1940), the Russian artist Konstantin Somov (1869–1939), the Spanish painter Ignacio Zuloaga (1870–1945), the Italian painter Giovanni Segantini (1858–1899) and the Austrian painter Albin Egger-Lienz (1868–1926).

Smrekar’s surviving correspondence reveals that he was a great admirer of Adolph Menzel, one of the most important German artists of the nineteenth century, a copy of whose monograph he purchased in Vienna. Apparently he stood in front of the shop window trying to make up his mind: should he buy food for the day or the book? The book won, and remained a precious memory of his student years. One exception is the painter, printmaker and illustrator Hanuš Schwaiger (1854—1912), known above all for his illustrations of fairy tales, whom Smrekar mentions in a 1905 letter to Janko Rozman. He says that he and Gaspari were thinking of going to see him in Prague in the spring, because he was a very fine chap.

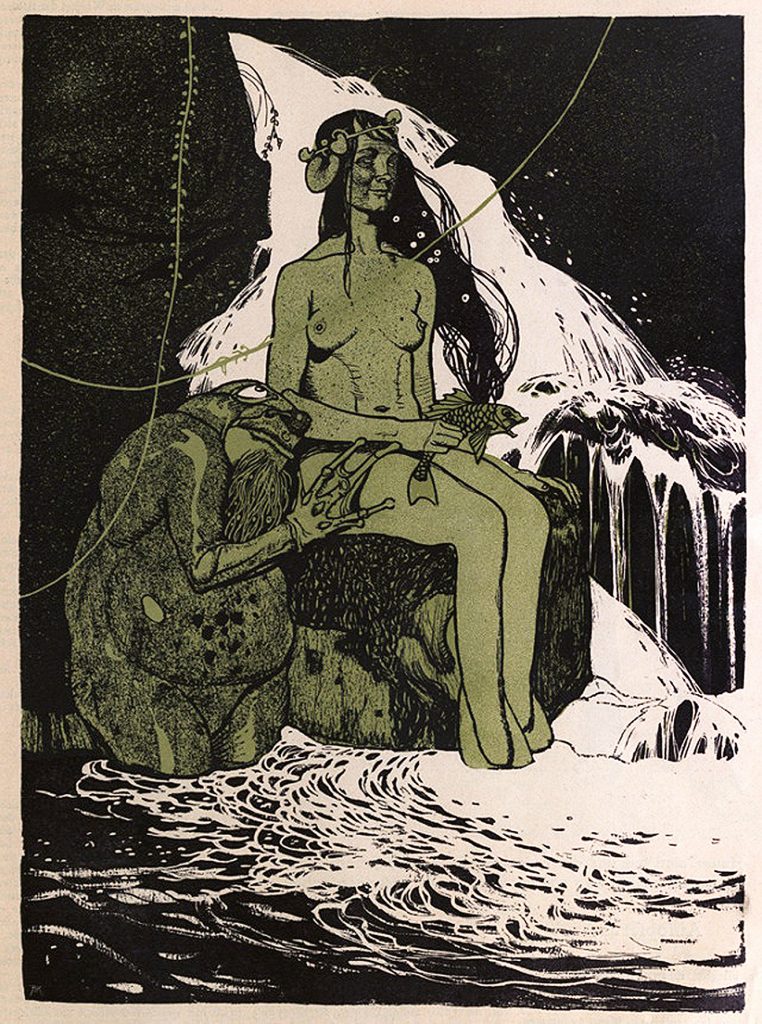

Water sprite, water man or vodnayoy is an aquatic spirit or demon resembling a naked old man with a froglike face, a green beard and long hair, his body covered with waterweed and mud, or with scales. Instead of hands he has webbed paws. He has a fish’s tail and glowing eyes. He derives from Slavic mythology and among the Slovenians, Czechs and Slovaks is known as the water man — a human figure with gills, webbed fingers and greenish skin and hair. His appearance is bizarre. He looks like a vagabond, in clothes that are too big for him and a straw hat with a ribbon on his head. He can sit for hours and hours by his pond, waiting. If anyone approaches him or swims in his vicinity, he is liable to pull them under the water and steal their soul. Identical creatures were drawn by Hanuš Schwaiger.

Torn between international artistic styles with their characteristic iconography and the national themes they had vowed to cultivate, the members of the Vesna group created a synthesis of the two. More than with fin-de-siecle decadence or symbolist spirituality, they associated the decorativeness of Art Nouveau to narrative storytelling and folk tradition, with elements taken from the everyday life of peasants, local folk tales, customs and traditions, folk songs and rustic crafts. We would look in vain for profound personal emotion or symbolic messages in the paintings of the Vesna group. They placed their lovers in a domestic environment and dressed them in traditional Slovenian costume, in order to bring a genuine Slovenian scene closer to us – something familiar to us, something beautiful and good. While typical Art Nouveau decoration was derived from the flowing and undulating lines of aquatic, tallstemmed and narrow-leaved plants or bellflowers, the Vesnans replaced it with stylised domestic flowers such as carnations, daffodils, lilies of the valley, snowdrops, tulips, ivy and meadow flowers. They did, however, retain the characteristic animals of Art Nouveau – swans, herons, snakes, peacocks – whose attractive forms suited the compositional rhythms of the period.. Trees played an important role in compositions. These included birches, poplars, oaks and, above all, willows, usually standing alone and pollarded, as well as old hornbeams and single forked trees alone in the landscape. Willows — and old hornbeams — are sometimes given anthropomorphic forms and change into demonic faces such as created by man, his fear and visionary imagination.

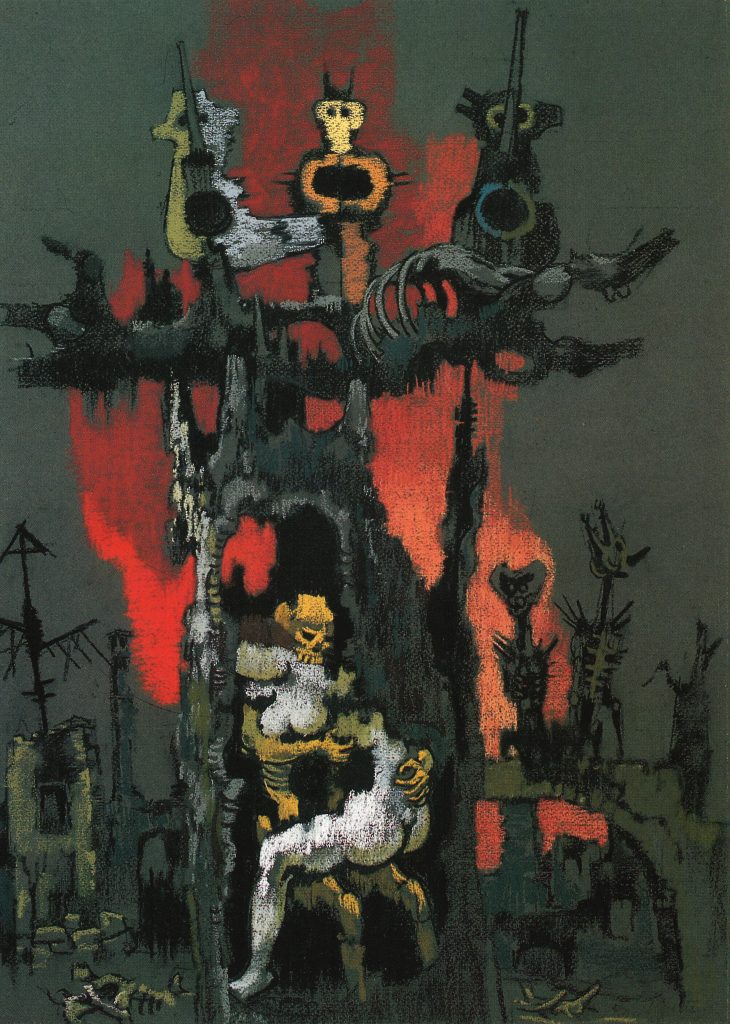

Within Slovenian art this process was intensified to the most gruesome level by the painter France Mihelič (1907–1998), a teacher at the Academy in Ljubljana after the Second World War.

Maksim Gaspari

The Slovenian Couple, 1907

National Gallery of Slovenia

The high point of sight leading the viewer’s gaze past the figures in the foreground towards the landscape extending in the background is a Romantic technique, while isolated trees in a landscape, views through blossoming branches or isolated figures below trees are compositional solutions familiar from Japanese woodblock printing. We find such compositions throughout the oeuvres of the members of the Vesna group, including in their later works, and if we compare the images of the remaining members they are touchingly similar. In the early works of the Vesnans it is, in fact, difficult to distinguish individual stylistic characteristics, something that points to their solid collective starting points. They were so united in terms of both content and form that it is sometimes difficult to determine the authorship of individual works. Although the group only existed from 1903 to 1906 and only held one group exhibition, even today these signs bind them together as a collective and a whole, in which each member occupies his own place in the mutual concord. Some members retained the characteristic features of the group right to the end of their artistic careers. Maksim Gaspari lived to the age of 97, while Gvidon Birolla returned to the same artistic starting points after several decades running the family business.

The latter print, as well as several others by Smrekar, show an interest in the Symbolist repertoire of Félicien Rops (1833—1898), the Belgian painter, printmaker, illustrator and caricaturist whose female figures were depicted as manipulators, schemers and bringers of misfortune. It was around 1915 that Smrekar began to work more intensively with prints, collaborating with Matej Sternen, who had several of Rops’s monographs in his library, and whose erotic, sometimes pornographic prints of female nudes and semi-nudes drew on Rops’s work.

When Smrekar left the safety of myths, fairy tales and folk legends, his mode of expression became critical, combative and merciless. He held up a mirror to society and called attention to cruel reality, pointed out society’s errors and delusions and predicted events to come with the vision of an apocalyptic seer. It must have been burdensome for him to see everything around him so disfigured and distorted. He himself said: “Lucky are the people who amuse themselves and laugh at freaks! You cannot measure the sorrow of a man who sees myriads of caricatures around the world, a man who wants to see a ‘human being’, yet sees instead a ‘disfigured’ animal, who wants to see the kingdom of God, yet knows only the rule of the lords’ lackeys, and has learned that there will be no end to caricatures!”

Social and political satire and caricature reached their highest point with Smrekar. He elevated them to an artistic genre in their own right and they stand out as the most characteristic works in his impressive oeuvre. In Smrekar’s case, however, everything he saw and felt, everything that moved and shocked him, was given form, and is often barely comprehensible. As a result, he was able to elicit laughter from the viewers of his works, who frequently — though wrongly — described him as a humorist. He himself firmly rejected this label, writing instead that he had come to know man as “a sad caricature that contrasts starkly with ideal theories and is for the most part a creature of loathsome habit” and that it was thus no wonder that he had become “so much a caricaturist and an almost absolute cynic, like all despairing, sceptical idealists.” (Smrekar 1931)

Understandably, then, Smrekar’s models must be sought in those artists who addressed the same subjects, who used their art as a weapon against authority and, consequently, in those artists who shared Smrekar’s fate.

Smrekar earned his designation “PV”, which stood for politisch verdachtig (politically suspect), on his police file by following the example of Hans Holbein the Younger, who included veiled allusions to various important political figures of the day in his cycle of woodcuts The Dance of Death, and for giving the torturer in his depiction of the martyrdom of St Catherine for 25 November (her feast day) the features of the Emperor of Austria, Franz Joseph I.

In the post-war period, Smrekar contributed drawings to various brochures published by the Slovenian Social Democratic Party for May Day celebrations. Several of these illustrations are explicitly anti-capitalist and anti-militarist. The drawings have not survived, but some of them are known from postcards published, for example King Capital, a fat man in a clown suit seated on a throne and growing fat at the expense of the starving masses; a variant of this drawing with the same title – King Capital – depicts a mountain-sized figure, tied to the ground by his hands, with masses of workers pressing against him, so that the overstuffed capitalist throws up coins. The two drawings may be linked to Smrekar’s statement that “the devout worshippers of capital saw an increase in their coffers, their bellies and their pride.” They are identical in terms of idea and content to Gargantua (1831), a lithograph by the French artist Honoré Daumier (1808–1878) that shows the corpulent figure of the French king Louis Philippe seated on a throne while a series of ill-nourished labourers carry sacks of coins up a ramp into his mouth.

The Mirror of the World cycle (1932–1933) is the powerful culmination of the last act of Smrekar’s oeuvre, although not its final epilogue. In a series of complex compositions packed with detail he transformed the whole of the visible world and created the hell and heaven he carried within himself. The result was a set of almost unintelligible drawings characterised by a confused blend of the iconography of past millennia, in an expression of despair, hopelessness, chaos, degeneracy and abuse at every level. When the art historian Stane Mikuž was attempting to penetrate Smrekar’s artistic essence, he wrote, among other things, that his mentality was like “a veritable witch’s cauldron”. He likened him to the Belgian artist Félicien Rops, who once said to a friend: “Sometimes it seems to me that I am a mythological creature that has been impregnated by the devil; a thousand misshapen creatures live their evil lives inside me and somehow, with goodness or with force, I must expel this thing from myself.” (Mikuž 1952)

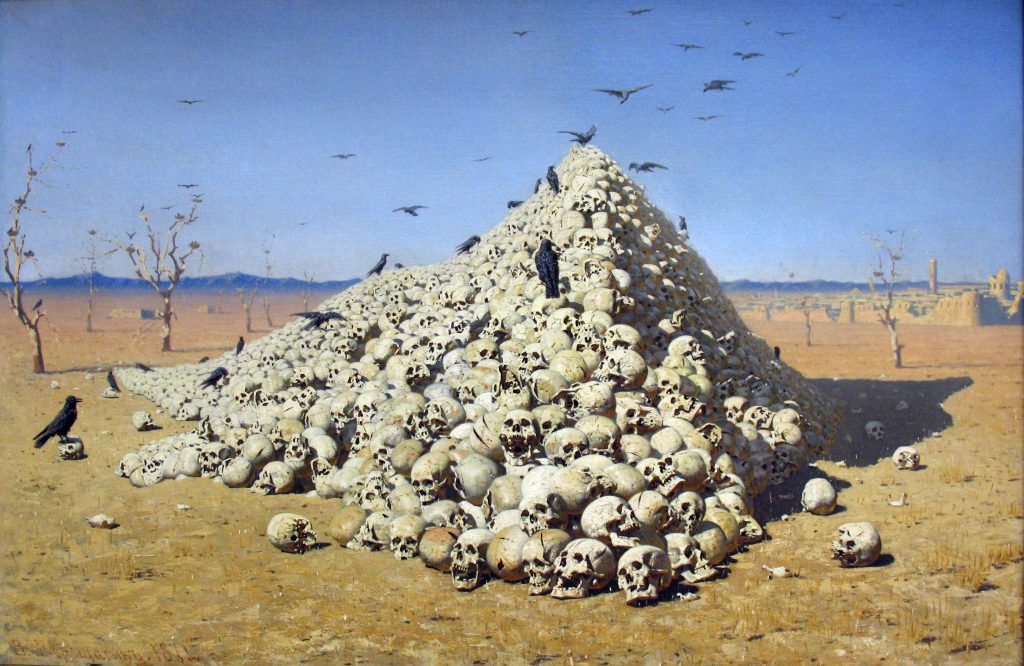

Smrekar borrowed from Egyptian and other ancient iconography in the cycle and the manner in which he filled the space and interwove the figures in the drawings are reminiscent of the scenes of hell, fallen angels or dances of death from paintings in past centuries. His rich drawing and fertile imagination link him to artists such as Gustave Doré or the Czech painter Maximilian Pirner (1854–1924), while the apocalyptic visions and invisible terrors connect him to Alfred Kubin. In terms of content, parallels can be sought with artists who tackled more convincing but also tragic topics, such as the Spanish painter Francisco Goya in his cycle of prints entitled The Follies (1816–1824) and, in particular, in The Horrors of War (1810–1814), where he declared his aversion to political violence and all his loathing and disgust at such actions, when all thoughts of reason, freedom and humanity were forgotten; or with the realistic battlefield scenes by the Russian painter Vasily Vereshchagin (1842–1904), who believed it to be necessary to paint the horror, fear and disastrous consequences of fighting in order to deter humanity from bloody wars.

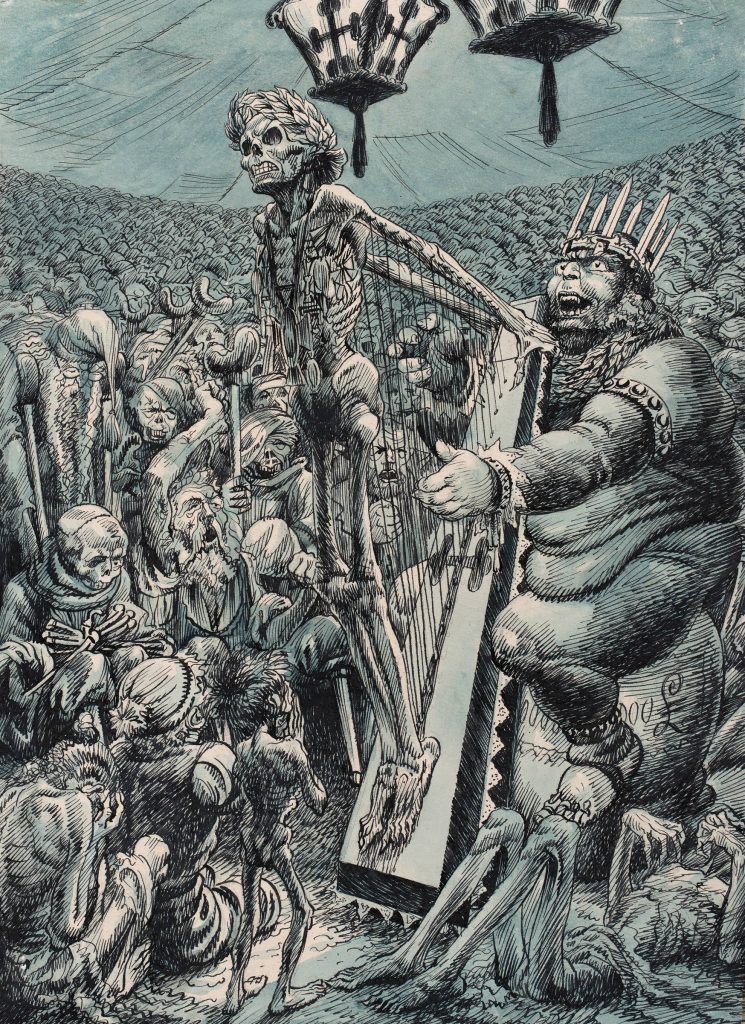

Hinko Smrekar

The Harp of Death, from the cycle Mirror of the World XIV, (1932‒1933)

National Gallery of Slovenia

The nightmarish scene is set inside a great circus tent, where in the dim light of two lanterns, in the midst of an endless multitude of living corpses, the fat figure of a man — a capitalist — sits on a sack of money, a crown of daggers on his head. He is playing a harp made from a coffin and a skeleton, the latter hung with medals and crowned with a laurel wreath, and singing a hymn to his own profit.

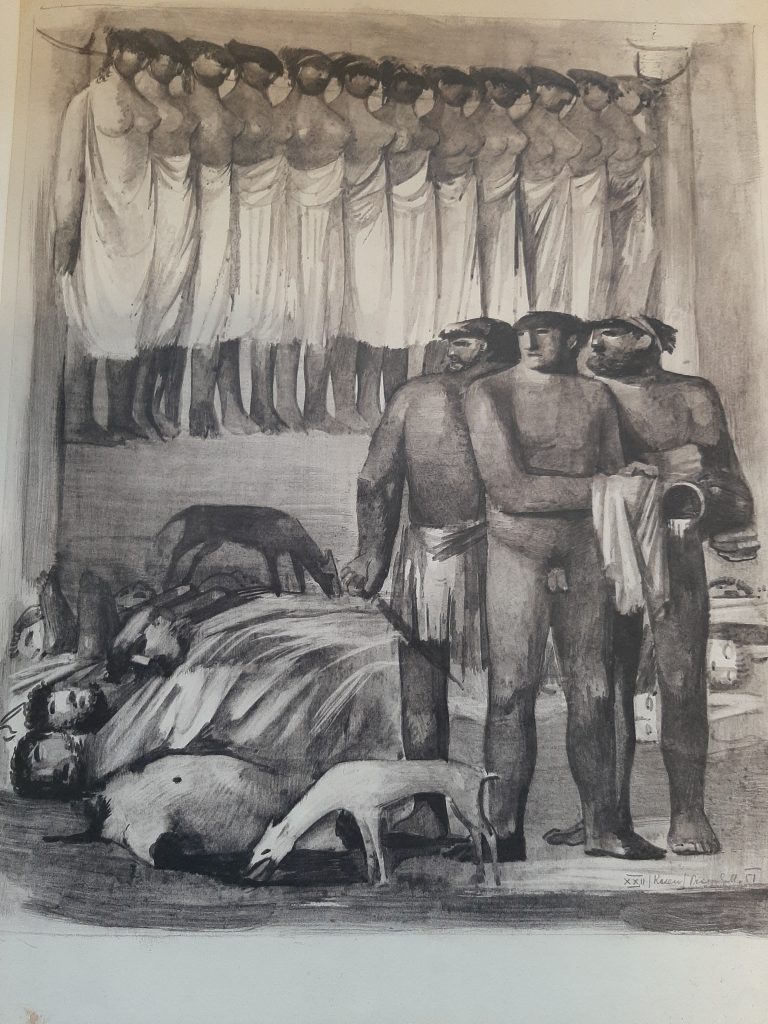

Marij Pregelj

Telemachus follows Odysseus’ orders and punishes the slaves and the shepherd Melanthius, illustration for Homer’s Odyssey (XXII, 461‒477), 1951

The drawing Dictator’s Avenue (cat. no. 1195) is a prophetic one and shows, instead of an avenue of trees leading to the castle at the top of the hill, an avenue of hanged men — like those that would shortly begin to appear throughout the world during the Second World War. A similar subject was used by Marij Pregelj (1913–1967) as a criticism of war in an illustration for Homer’s Odyssey, where he drew the slave girls who had lain with the suitors, killed on Odysseus’ orders, as hanged women. By 1951, the year these illustrations were drawn, Odysseus has lost his paradise, been wrested from Homer’s verses and become a hero of our age. “He has come in a multitude of myriad destinies, in a century of homeless, of refugees, of the many who perished even as they fled, of the countless thousands who fell victim to massacres and prisons before they could cross the barbed wire of boundaries placed everywhere.” So wrote the classical philologist Jože Kastelic with regard to these illustrations.

Smrekar did not stop working during the occupation. The images he drew were ones that no newspaper would dare to publish, so instead he exhibited them on a noticeboard outside his house. The figures thus exposed to public ridicule ranged from Prince Paul of Yugoslavia to Neville Chamberlain, Mussolini, Hitler, Emilio Grazioli, Marko Natlačen, members of the clergy and others. Few of these drawings have survived and it is believed that his neighbours removed them from his house and destroyed them after learning of Smrekar’s arrest so they could not be used as additional evidence against him. Some are drawn in sketch-like fashion, while others are more carefully drawn and in large formats. It is believed that these drawings are what sealed his fate.

Hinko Smrekar

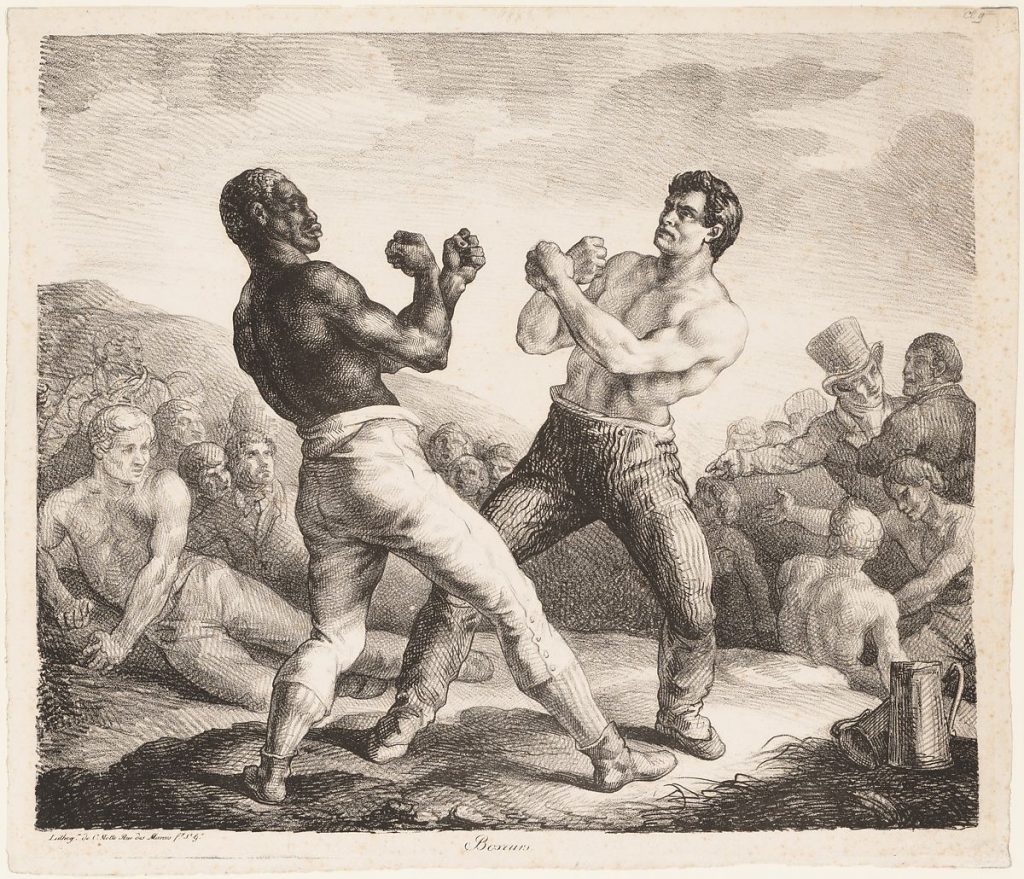

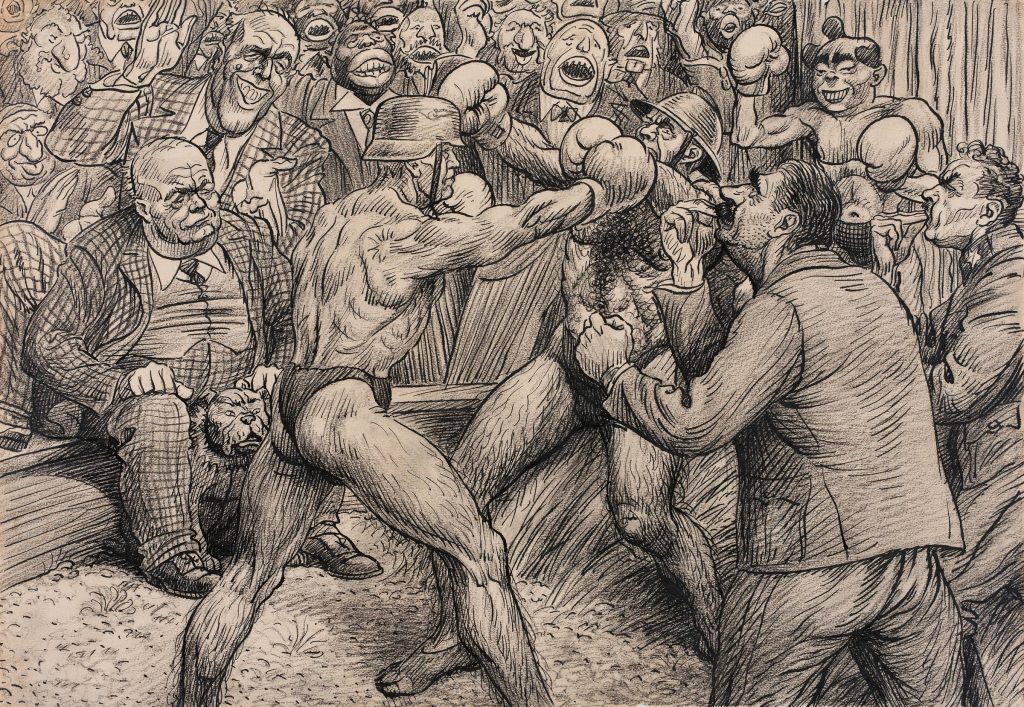

Boxing, (c. 1941)

National Gallery of Slovenia

Smrekar often illustrated political events by setting the scene in a boxing ring. Boxing was a very popular sport from the early 19th century onward, especially in England, from where it spread across Europe. The market was flooded with cheap prints of boxing scenes, which among others inspired Théodore Géricault’s lithograph Boxers in which he was mainly concerned with a technical challenge. Smrekar’s Boxe en masse (1940, cat. no. 1661) depicts a fight between the Allies and Axis powers. Churchill and Hitler have clashed in the ring, a laughing Roosevelt is the referee of the match, Stalin waits for his turn in the audience, and Pope Pius XII prays in front of the ring.

On 30 September 1942 Smrekar was arrested near his home in Ljubljana by an Italian patrol, who found on his person a copy of Radio Vestnik (Radio Gazette), a clandestine publication of the Liberation Front. At his last interrogation, Smrekar remained what he had always been as a man and an artist. He said to his executioners: ‘I declare that I do not wish to live under a regime as filthy as Fascism. I demand that you shoot me!’” He was thus executed, without due process, on Thursday 1 October 1942, five minutes before half past five in the afternoon, in Gramozna jama (Gravel Pit) in Ljubljana, where the occupying forces had shot at least 185 civilians during the war. The day after his execution, his grave was covered with flowers.

Select Bibiliography

Henrik Smrekar, Ad acta H. S. ca. »Slov. Narod«, Dan, 1/281, 8. 10. 1912, p. [3]

Dni mojih lepša polovica / Avtobiografija I.) del. od l. 1883‒1903 / Napisal in narisal / H. S., 10. 3. 1927, transcript (National Gallery of Slovenia, Fond D, NG D 145-1)

Hinko Smrekar, Jaz Hinko Smrekar, po božji milosti excentric-clown slovenskega naroda, Naša knjiga, 10, Zemun, 1931

Saša Šantel, Hinko Smrekar – petdesetletnik, Jutro, 14/161, 13. 7. 1933, p. 3–4

E[lko] Justin, Hinko Smrekar in njegove podobe. Odlomek iz zapiskov o pokojnem umetniku in njegovem ustvarjanju, Tovariš, 4/41, 8. 10. 1948, p. 970‒972, 982

Stane Mikuž, Po razstavi Hinka Smrekarja, Ljudska pravica, 13/46, 15. 11. 1952, p. 10

France Stele, Slikar Maksim Gaspari petdesetletnik, Slovenec, 61/23a, 28. 1. 1933, p 3–4

Jure Mikuž, Jože Kastelic v: Homer, Odiseja, Ljubljana 1991 (folder with reproductions)

Robert Simonišek, Slovenska secesija, Ljubljana 2011

Author: dr. Alenka Simončič, 2022