Learn more about Smrekar and his mates by going through the (Slovenian) alphabet.

Smrekar's Alphabet

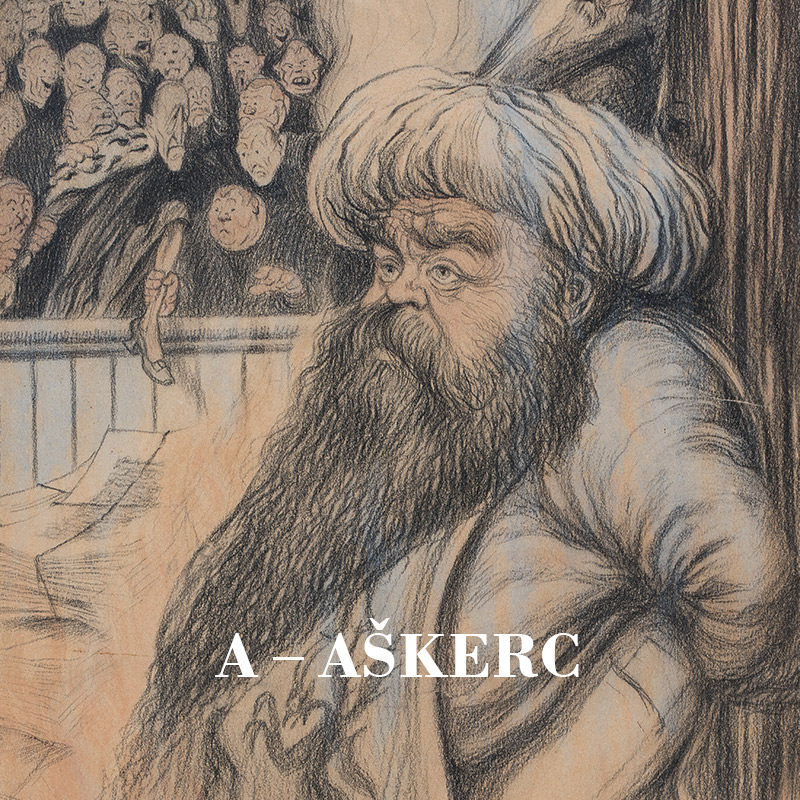

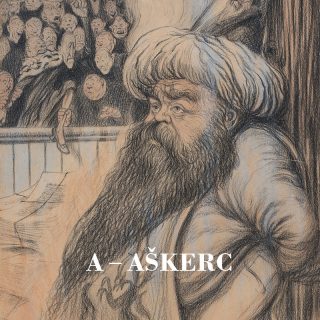

Anton Aškerc (1856−1912) was an epic poet, a Catholic priest and the first archivist at Ljubljana Town Hall. Smrekar produced two drawings of him as a heretic being burned at the stake. In 1905 Aškerc had published a historical epic poem about the Protestant reformer Primož Trubar, in which he presented him as a revolutionary. This provoked discontent among the clergy on the grounds that it was offensive to them. Aškerc is depicted at the stake wearing a turban-like head covering, the conical top of which is decorated with a portrait of Trubar with horns. On his feet Aškerc wears slippers with curling, pointed toes.

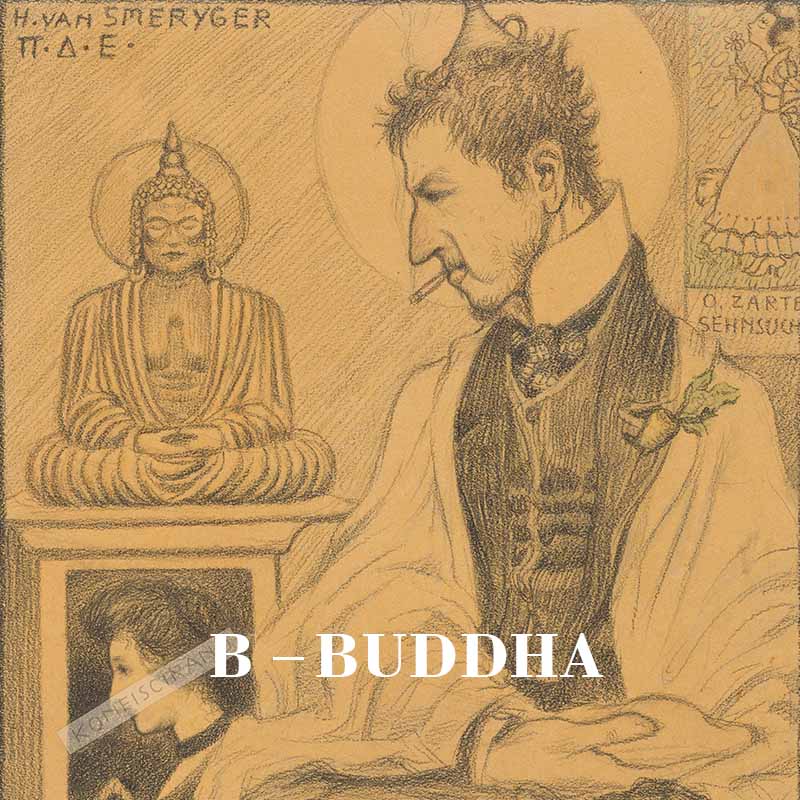

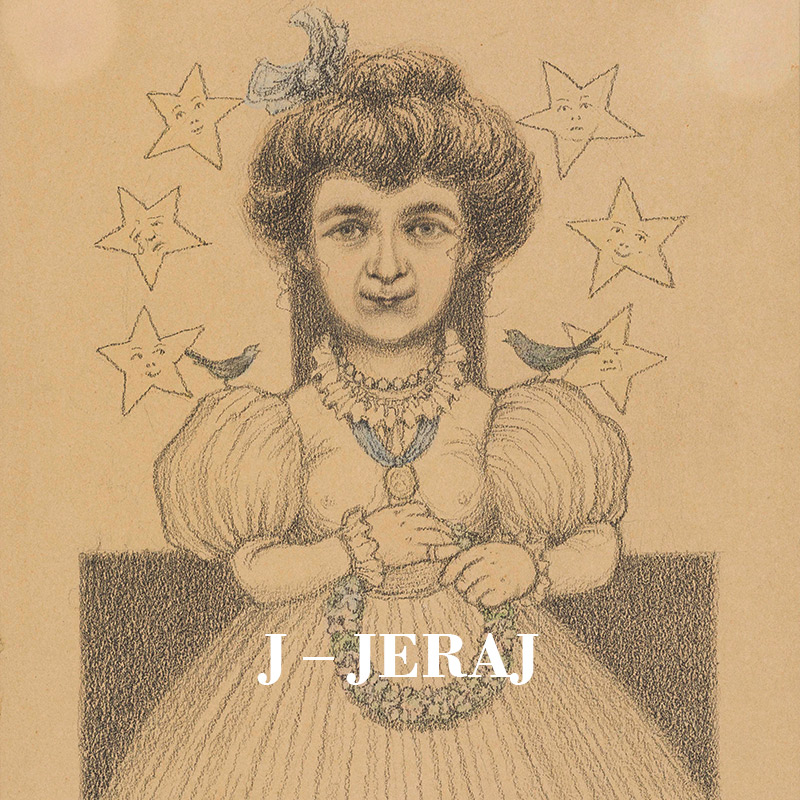

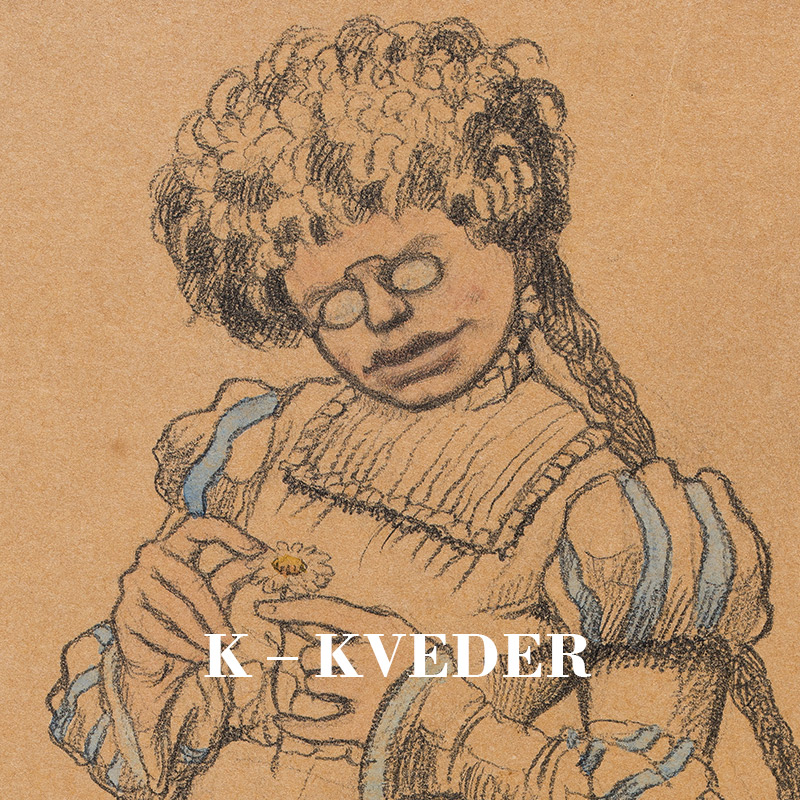

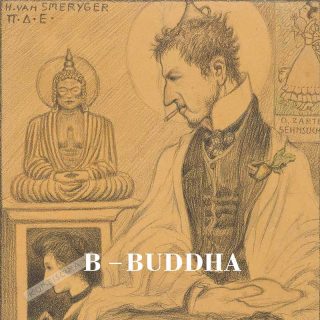

Smrekar depicted himself in a Buddha pose with a saint’s halo. He wears an inverted funnel on his head and has a cigarette in his mouth. A mandrake root – a medicinal plant – is placed in his buttonhole as a symbol of unrequited love. He is looking towards a statue of Buddha on a pedestal, on which a woman is depicted in profile. This is thought to be a portrait of the well-known Slovene poet Vida Jeraj, with whom Smrekar was once in love. On the wall behind him is a poster showing a young woman, another of Smrekar’s lost loves: the Slovene writer Zofka Kveder.

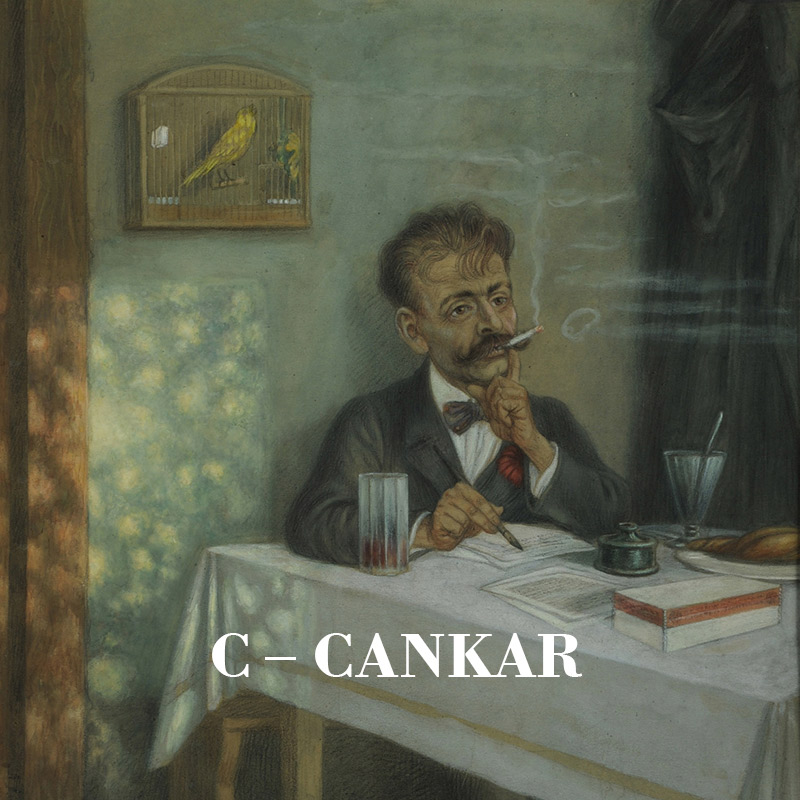

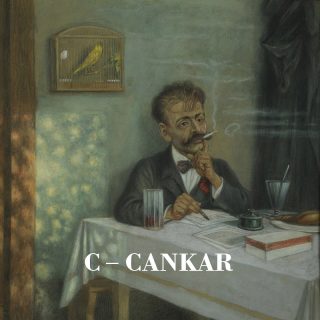

The writer, essayist, dramatist and poet Ivan Cankar (1876–1918) was a strong influence on the young Smrekar. It was under his influence that Smrekar began to develop a sharp, critical tone, which he then developed further in his caricatures. Smrekar did not only find a personal friend in Cankar, above all he saw him as a kindred spirit. The two socially engaged and combative artists were uncompromising in their search for truth. The essence of their works is not so much satire as a profound confession and a calling to account of society. On Cankar’s death, Smrekar wrote: “Since Ivan Cankar’s death I feel as though I am only half alive.”

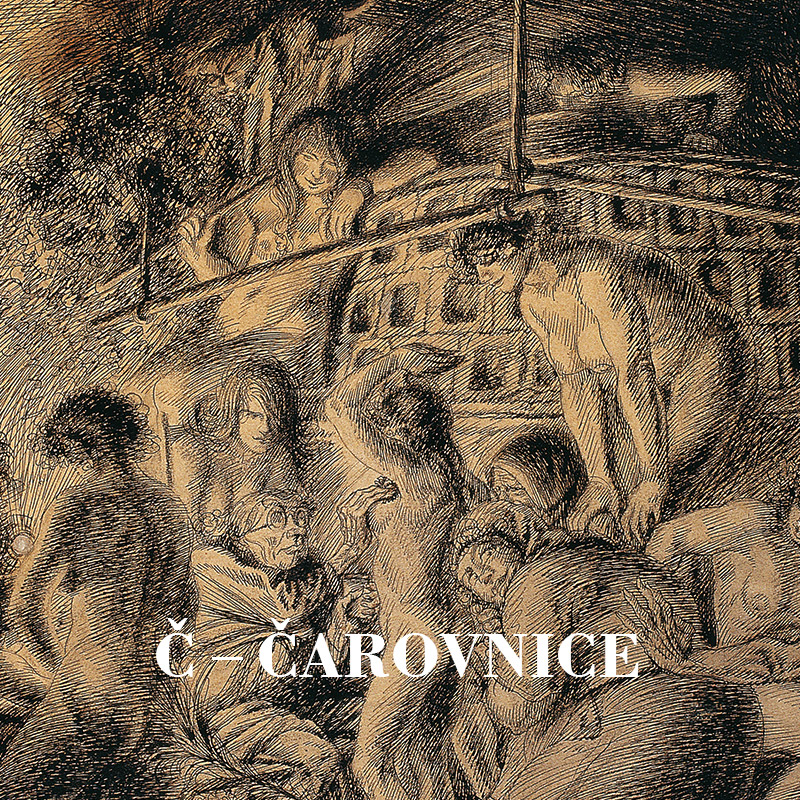

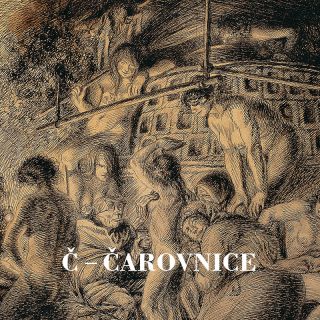

Witches were a frequent subject in Smrekar’s oeuvre. In terms of content, his works featuring witches and witchcraft drew on various folk tales, while in the formal sense they sometimes followed the art of the symbolists. The drawing Witches Preparing for Klek is thought to be Smrekar’s earliest work to show witches. It shows a group of witches getting ready to ride to Mount Klek. The older witches help the younger ones with their preparations. The devil stands discreetly by the door, waiting patiently for them. One of the young witches apparently closely resembles a well-known demi-mondaine from the Šiška district.

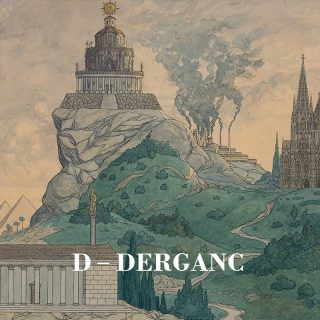

Dr Franc Derganc (1877–1939) was a surgeon and the owner of a private hospital in Ljubljana. Smrekar produced five drawings for him on themes suggested by Derganc himself. They are drawn in the spirit of classical antiquity and their ethical content is defined by the addition of Latin medical sayings. The Latin translation of Hippocrates’ aphorism “Vita brevis ars longa” (Life is short, art is long) appears on a drawing illustrating the development of art. Along the bottom of the drawing, three medallions linked by a garland contain portraits of Asclepius, Paracelsus and Derganc.

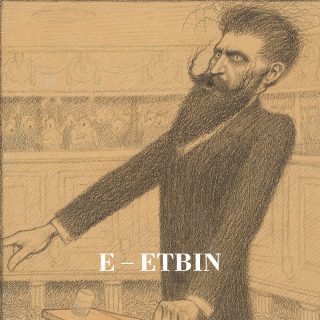

The socialist politician and writer Etbin Kristan (1867–1953) was a “renowned orator who was capable of inflaming crowds but was also very popular as a speaker among cultured intellectuals”. This is how he was remembered by Maksim Gaspari. Smrekar chose to draw him in his oratorical fervour. In Masquerade of Slovene Literati, Kristan is portrayed as a “red” or a sans-culotte with a Phrygian cap of liberty on his head and a bloody axe in his left hand.

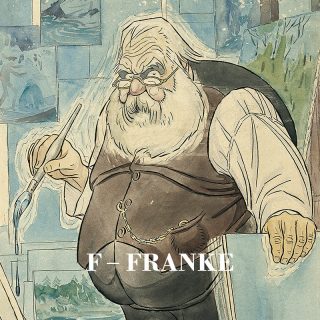

The painter Ivan Franke (1841–1926) taught drawing in Kranj and Ljubljana and was also involved in conservation. He served as the president of the Slovene Art Society and wrote widely on Slovenia’s artistic and historical monuments. He also wrote extensively on fishing. He was the originator of the artificial breeding of trout species in Slovenia and the author of a draft “Fishing Law for Carniola”. He also organised several artificial fish hatcheries in Slovenia. This is the reason why Smrekar depicted him as Triton in Masquerade of Slovene Artists. The caricature A Cold Tone (Grounding Canvases) is also associated with water.

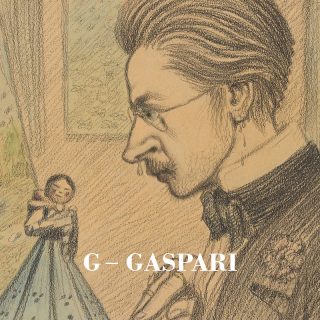

The painter Maksim Gaspari (1883–1980) was a founder member of the Vesna art club in Vienna in 1903. Gaspari and Smrekar were linked by a solid friendship dating from their Viennese years. They regularly visited Munich during the Oktoberfest and had numerous adventures there, which Gaspari recorded in his Memories of Hinko Smrekar. Smrekar drew Gaspari several times, frequently with little hearts. In 1907 he placed him in front of a canvas on which his characteristic landscape with a little hill and a church is already visible. He is about to complete the figure of a young woman in national dress.

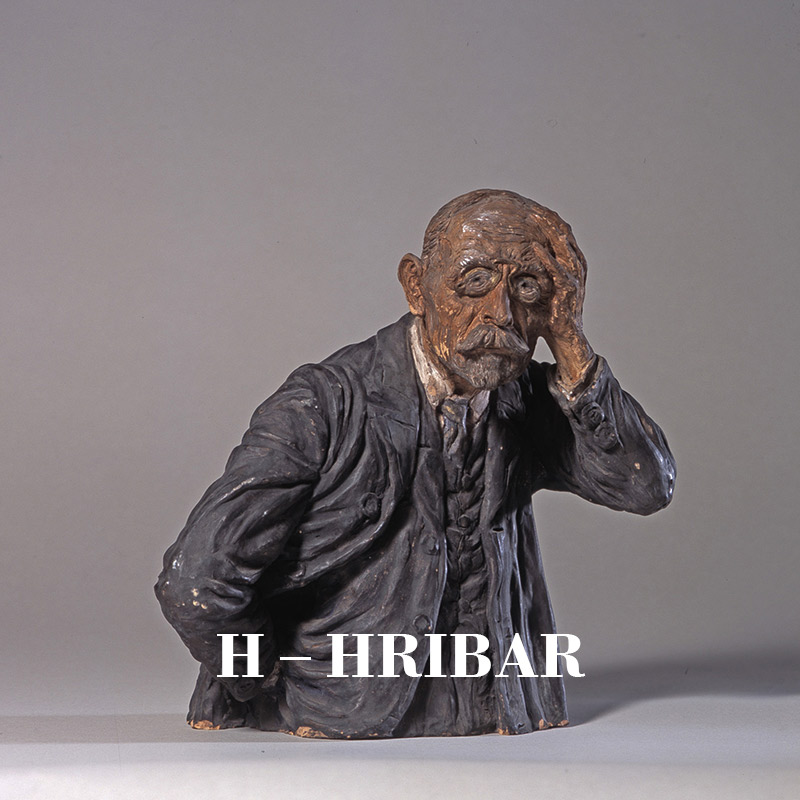

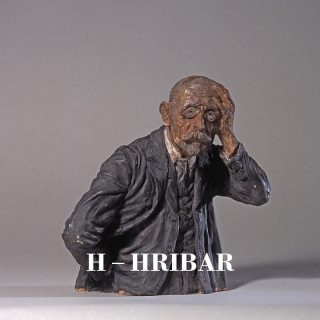

The banker, politician, diplomat and journalist Ivan Hribar (1851–1941) served as mayor of Ljubljana between 1896 and 1910 and was responsible for rebuilding the city following the great earthquake of 1895. Smrekar depicted him several times, most frequently in caricatures in which he appears along with his political colleague Ivan Tavčar. The two men were the leading figures of the National Progressive Party before the First World War. In the last year of Hribar’s life, Smrekar produced a figurine that captures the great patriot and enthusiastic representative of Neo-Slavism in a moment of reflection.

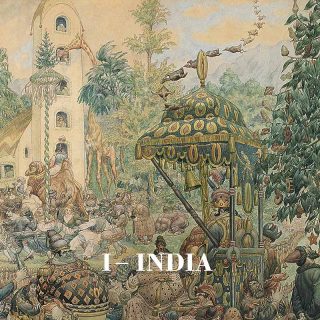

Cockaigne, also known as the Land of Milk and Honey or India Coromandia in Slovenian, is the promised land where all can enter but Evil. Smrekar’s first depiction of this subject dates from 1917, but the version from two years later is even more ambitious. The picture shows a lawn in front of a church that is filled with all manner of phenomena, creatures and curiosities, all serving to distract the attention of Evil. The fat man in the foreground is a conventional personification of Capital. In Smrekar’s own words: “The devout worshippers of capital saw an increase in their coffers, their bellies and their pride.”

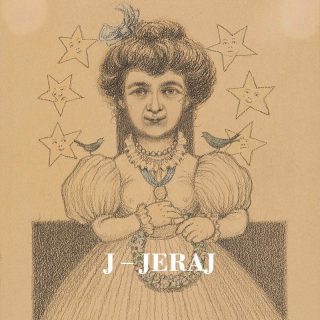

Vida Jeraj (1875–1932) was a Slovene modernist poet who hosted literary salons at her home in Vienna and in the village of Zasip near Bled in north-west Slovenia. Known for her unconventional and bohemian behaviour and style of dress, she is one of two loves of Smrekar’s mentioned by Gaspari in his Memories of Hinko Smrekar. Smrekar depicted the confident, thoughtful, independent young woman as a fashionably attired dwarf, with a series of accessories whose true meaning remains unknown to us. She is surrounded by a halo of six stars with facial expressions that indicate different moods. A pair of chirping birds perch on her shoulders and she holds a wreath in her hands.

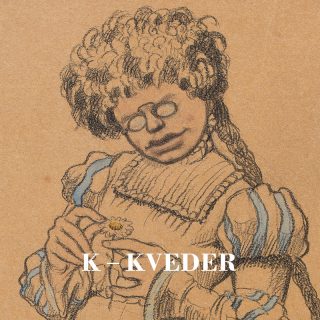

The writer and journalist Zofka Kveder (1878–1926) was a tireless promoter of Slovene literature in the powerful and influential cultural milieu of Prague. It was thanks to her that Cankar’s comedy For the Welfare of the Nation was given its premiere performance in Prague in 1905, after censorship had prevented its staging in Slovenia. She was a spirited harbinger of women’s emancipation and one of Smrekar’s unrequited loves. In this drawing from around 1907 she appears as an independent, elegant lady holding a daisy, from which she is plucking the petals.