Signatures

His early works, and also his signatures, are characterised by youthful mischievousness and enthusiasm. Full of idealism, he and his fellow artists – all of them then living in Vienna – decided that they would serve the nation and create genuinely national art. They used to send illustrated postcards to each other, the texts of which were written in slang and are frequently incomprehensible. Presumably they never imagined that these would be read by a wide audience and analysed by art historians.

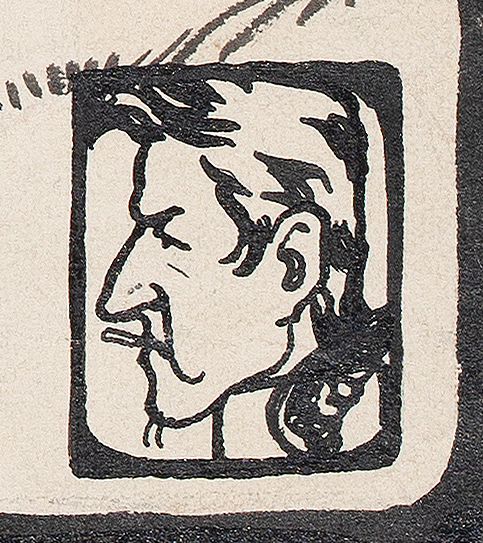

Fig. 1

Hinko Naparossa, illustrated postal card for Anton Mrak, 1902, detail, National Gallery of Slovenia

Fig. 2

Enrico v. Naparossa, from illustrated postal card for Anton Mrak, (1902), National Gallery of Slovenia

Fig. 3

Hinko Žouna, from illustrated postal card for Pavla Potočnik, 1903, private collection

Fig. 5

Svinko Sifla, from Pilherrimus Slut, (1903), private collection

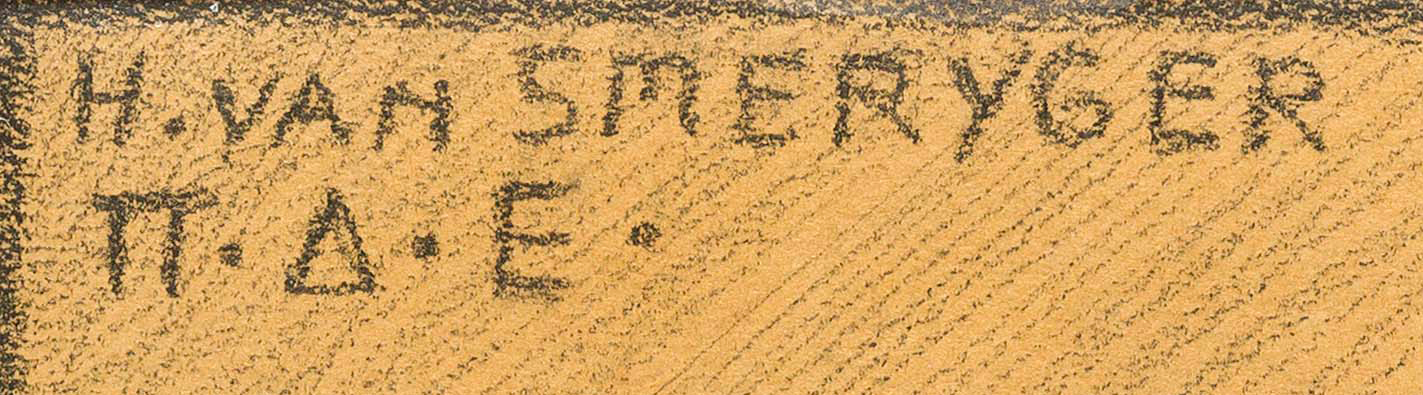

Several of Smrekar’s earliest signatures appear on these postcards, for example Hinko Naparossa, Enrico v. Naparossa, Hajnrich Žouna (a reference to the Slovene expression pije kot žolna, meaning “drinks like a woodpecker), Žane, Don Kihot, Gorgonzola. Many of these were presumably in-jokes, while the signature Michelet may relate to the figure of “Der deutsche Michel”, a naive and gullible individual standing as an allegory of the German nation. The oldest signatures also include Svinko Sifla, an allusion to syphilis and Smrekar’s life in Vienna, H. Van Smeryg(g)er, Tone Poper and, a more descriptive signature in the style favoured by the medieval masters, Hudobni Mihec or “Wicked Mike” (Smrekar was only eight years old at the time). (Figs 1–5)

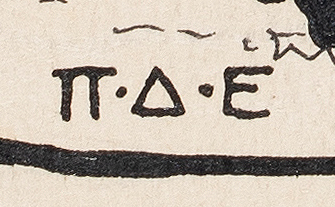

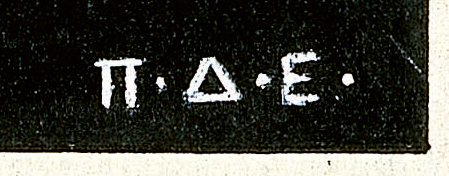

In 1905 and 1906 Smrekar and his colleagues Maksim Gaspari, Gvidon Birolla and Fran Tratnik collaborated with the satirical newspaper Osa (The Wasp). Smrekar had the idea that instead of signing himself with his name he could use a self-portrait – in profile, with or without a cigarette, or even with a woman’s breasts and the enigmatic inscription Π. Δ. Σ. (pi ‒ delta ‒ epsilon), the precise meaning of which remains unknown. One of the plates for Osa in the National Gallery collection has a secondary inscription explaining that the letters stand for Pante Dreke Estin, which could be translated as “Everything is Shit”. This explanation may not be so very far-fetched, given that Smrekar was fond of drawing excrement alongside his signatures. On one occasion he even drew it on his head. Pleased with the success of his first solo exhibition in Ljubljana, he added it to his public expression of thanks. It is also hidden in the wealth of details on the poster advertising another solo exhibition a year later. (Figs 6–11)

Fig. 6

St Nicholas to Slovenians, (1905), detail, private collection

Fig. 7

Voting Reform or the Radical Operations by Doctor Gautsch, (1906), detail, private collection

Fig. 8

A Platonic Party, (1906), detail, private collection

Fig. 9

Sebastian on a Pilgrimage, 1906, detail, location unknown

Fig. 10

Blind Man's Buff, 1906, detail, private collection

Fig. 11

Public Acknowledgment, 1940, detail, National and University Library, Pictorial Collection, Ljubljana

A signature with the same three Greek letters in the Latin translation P. D. E. can also be seen in his self-portrait as Buddha from 1908. The original title of this self-caricature was apparently The Wretchedness of Unrequited Love. Smrekar depicted himself in a Buddha pose with a saint’s halo. He wears an inverted funnel on his head and has a cigarette in his mouth. A mandrake root – popularly believed to have healing properties and an unusual and mysterious power – is placed in his buttonhole, in this case as a symbol of unrequited love. (Fig. 12)

Smrekar used the same signature on the cover of Ivan Cankar’s Tales from St Florian Valley, a work that turns a critical eye on society’s morals and was published the same year. Cankar wished Smrekar to contribute several illustrations for this book, but Schwentner only requested a cover. Smrekar responded to this parsimoniousness by limiting himself to a drawing of two large bats, with several smaller ones in the background rising up above the broken crosses of a graveyard. This signature was clearly also evidence of some anxiety or negative emotions, and Smrekar apparently later admitted that these letters were a sign of his extreme nihilism at the time – and that their meaning remained obscure even to Cankar until the book was published. Smrekar later told the author that with these letters he had wanted to “give vent to the fear that he was drowning in excrement and that it would soon cover him.” (Fig. 13)

Fig. 12

Self-Portrait as Buddha, (1908), detail, Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana

Fig. 13

Draft of front cover page for the book Tales from St Florian Valley, (1908), detail, National Gallery of Slovenia

For the 1913 social satire Bazaar for the Benefit of Actors Abandoned by the Province of Carniola he took advantage of the similarity of his surname to the word smreka, meaning spruce, and instead of a signature placed a little drawing of a spruce tree in the bottom left-hand corner, adding the letter R to give “Smrekar”. This work was a comment on the combination of circumstances that had led to the closure of Ljubljana’s Provincial Theatre as a result of a lack of support from the Carniolan Provincial Council. The drawing depicts the translator and art critic Fran Kobal, who in 1912 was a member of the theatre management, as a vendor/publicist under a large market umbrella. Hanging from the umbrella like lottery prizes are Smrekar (far right), Gaspari as a pedlar with the bag containing the numbers (centre) and Ante Gaber (left). The sculptor Lojze Dolinar hangs from the stall itself. The scene alludes to the charity lottery organised by the General Women’s Society for the benefit of needy artists, at which the prizes consisted of works by Slovene painters and sculptors. The same signature was used by Smrekar’s fellow artist Elo Justin a month after Smrekar’s death in 1942. Justin published a veiled obituary in Jutro in the form of a rebus showing a felled spruce tree (smreka) lying under a coffin, with the words “The End” and the letter “R” next to it. (Fig. 14)

Fig. 14

Bazaar for the Benefit of Slovenian Actors Abandoned by the Province of Carniola, 1913, detail, National Gallery of Slovenia

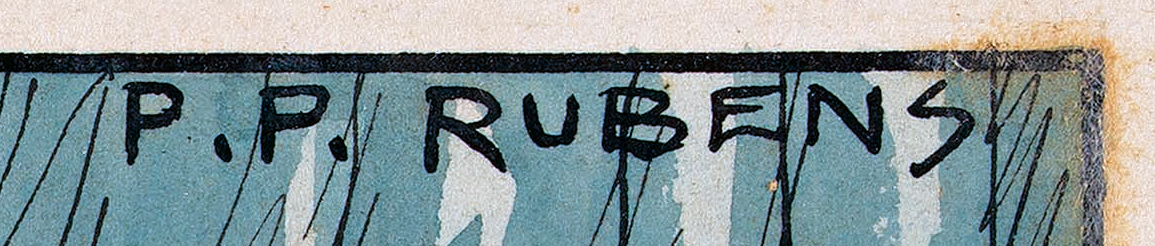

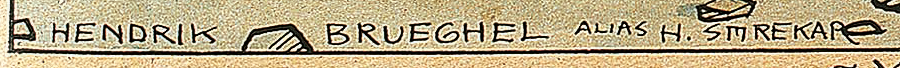

Between 1918 and 1927 Smrekar liked to append the abbreviations V. R. M. P. or V. U. M. P. to his signature (perhaps standing for something vulgar along the lines of “up yours”) and signed himself with famous names from the history of art, such as P. P. RUBENS, or with the surname BRUEGHEL alongside the first name HENDRIK, or with one-off names such as AREH SMREKAR, ENRICO SMRECARETTI, GIOVANNI SENZAPARA, ENRÍCO PIZZICAGNOLA, ŽANE BRUNDA, JAKA KRULC, Aleš Sirota or RAMON DE SÍSCARA. After 1927 he mainly signed himself with the initials HS or, with his full surname, as HSmrekar. (Figs 15‒20)

Fig. 15

Miss Fini Poderžaj in Her Wartime Family, (1919), detail, National Gallery of Slovenia

Fig. 16

Wartime Wooers of 1918, 1918, detail, National Gallery of Slovenia

Fig. 17

Nikola & Stipica or an Old Fox in Trouble, 1926, detail, National and University Library, Manuscript Collection, Ljubljana

Fig. 18

Yugoslavia and Guest, (1926), detail, private collection

Fig. 19

Mussolini, 1926,detail, location unknown

Fig. 20

Albanian Broth, 1927, detail, location unknown

Author: dr. Alenka Simončič, 2022