Self-Portraits and Self-Caricatures

The earliest self-portraits are on illustrated postal cards sent to friends from, variously, Innsbruck, Vienna, Kranj, Munich and Ljubljana. Smrekar’s illustrations largely consisted of his commentary on everyday events. In 1903 he was diagnosed with a high degree of neurasthenia, which led to his scholarship to study law in Vienna being suspended. Smrekar withdrew his application to sit the state examination, sold all his law books and spent the proceeds on drink, and embarked on his career as an artist. On one postal card he depicts himself lying on a sickbed with a doctor examining him and writes that he is going to have himself “shut up in an institution for the nervously ill” because he is “seriously neurasthenic”. On another he draws himself with his head buried under his books while a celestial being, a personification of the state examination, scatters gold coins over him. (Fig. 1, 2)

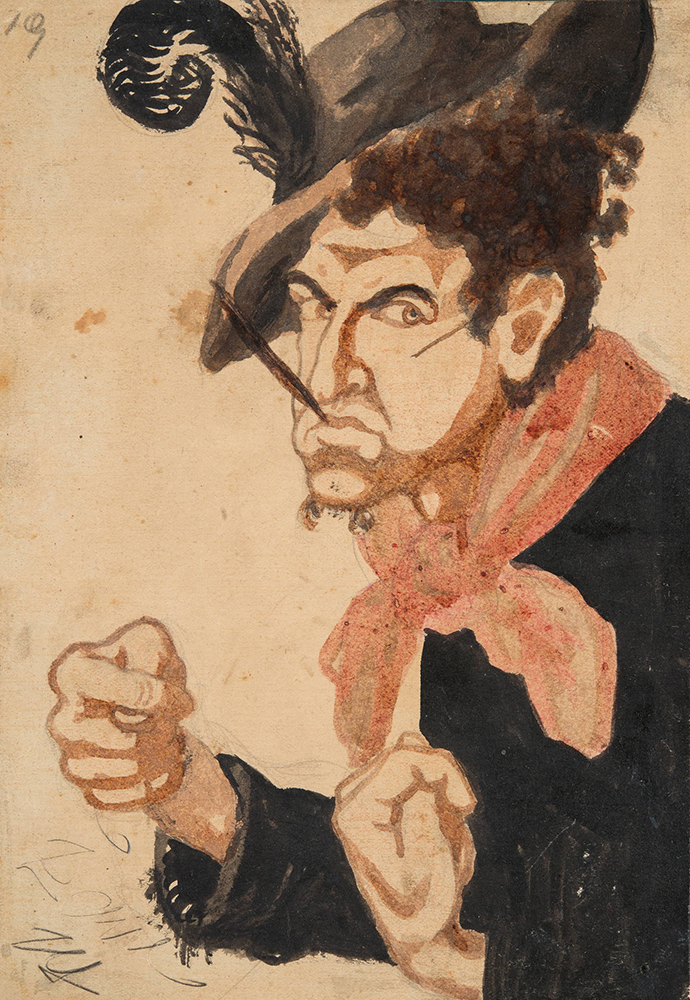

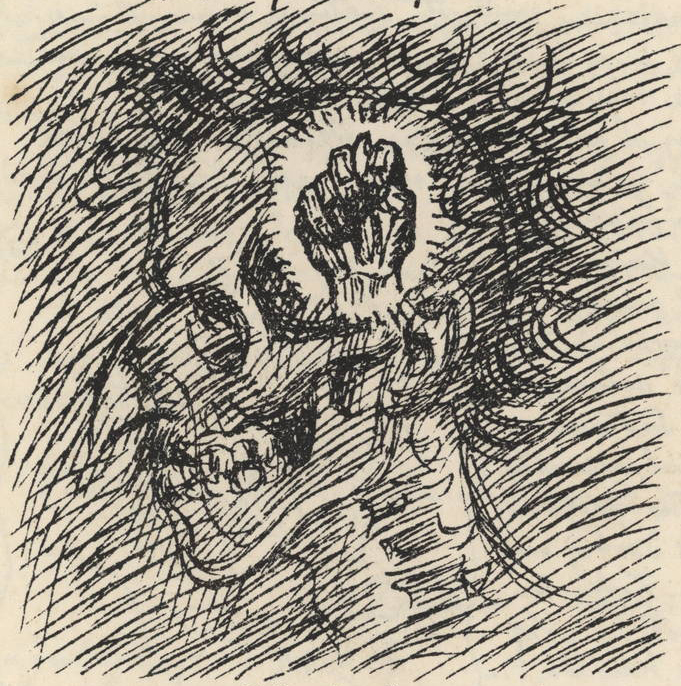

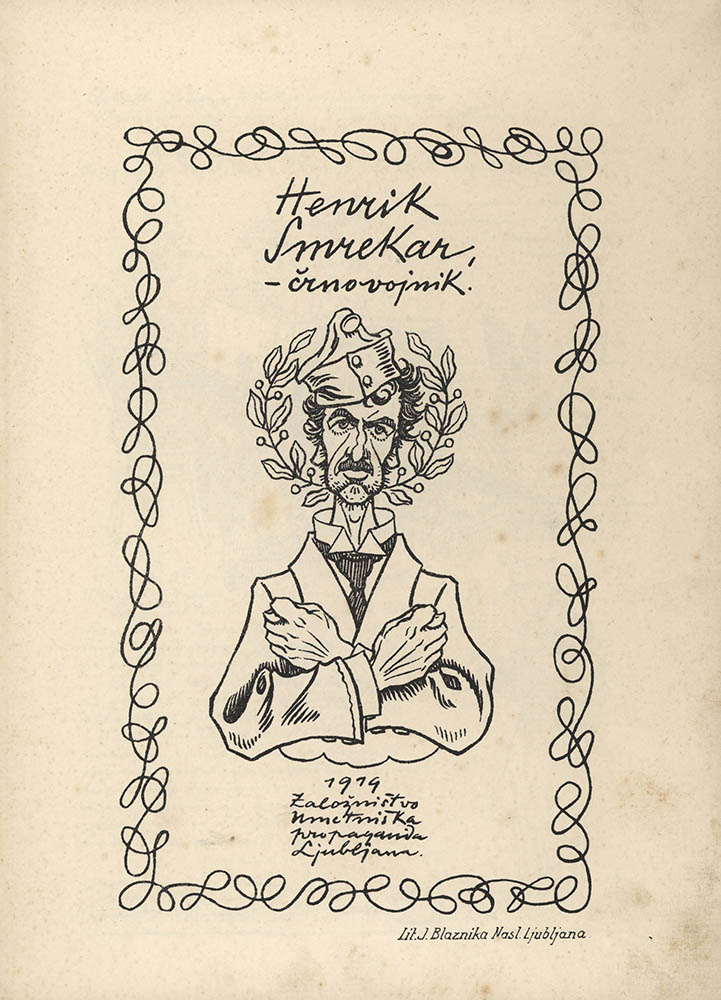

The young artists of the Vesna club played an important role in introducing the art of the Vienna Secession to Slovenia. In Vienna and Munich — which in the central European context were synonyms for artistically progressive cities, with their artistic atmosphere and bohemian lifestyle — they were exposed to modern trends. They followed new developments closely and attended exhibitions involving the participation of international artists, in this way encountering the latest directions in art. One of Smrekar’s first self-portraits is Žane, perhaps the most fashionable image in his entire oeuvre. It reflects his cynicism and his ability to adopt and adapt contemporary themes. He depicted himself in the style of Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters, a fashionable hat with a feather on his head, a red scarf round his neck and a Virginia cigar in his mouth, as he strikes a defiant pose and makes a vulgar gesture with his fists. The youthful rebelliousness evident in this pose is largely directed against the limitations of the bourgeois mentality. It finds an exact parallel in a later self-portrait, an “X-ray image” of his head drawn more than ten years later. Smrekar published the latter in 1919 in his illustrated (auto-)ironic autobiography Henrik Smrekar – črnovojnik (Henrik Smrekar – Landsturm Soldier), in which he describes the years 1915 and 1916, when he was interned in several different camps following an anonymous denunciation.

Satire had its predecessors in Slovenian art in the paintings that adorned the wooden end-panels of beehives, which were very familiar to Smrekar. He may have even created paintings for beehive panels on occasion, just as Gaspari did. A surviving photograph shows a drawing in which Smrekar has transformed the Old Wives’ Mill, a popular scene on beehive panels, into The Mill of Rejuvenation, in which he appears in person helping the women climb into the mill and to which he has added the caption “Married in 3 weeks!” (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5

The Mill of Rejuvenation, location unknown

He also used self-caricatures as signatures, most frequently in his illustrations for the satirical newspaper Osa (1905–1906), in which he appears in profile, with or without a cigarette, or even just as a nose in profile, and so on. In 1906 he drew himself for the first time as a hanged man, in this way expressing his criticism of the limitations of society. (Fig. 6, 7, 8, 9)

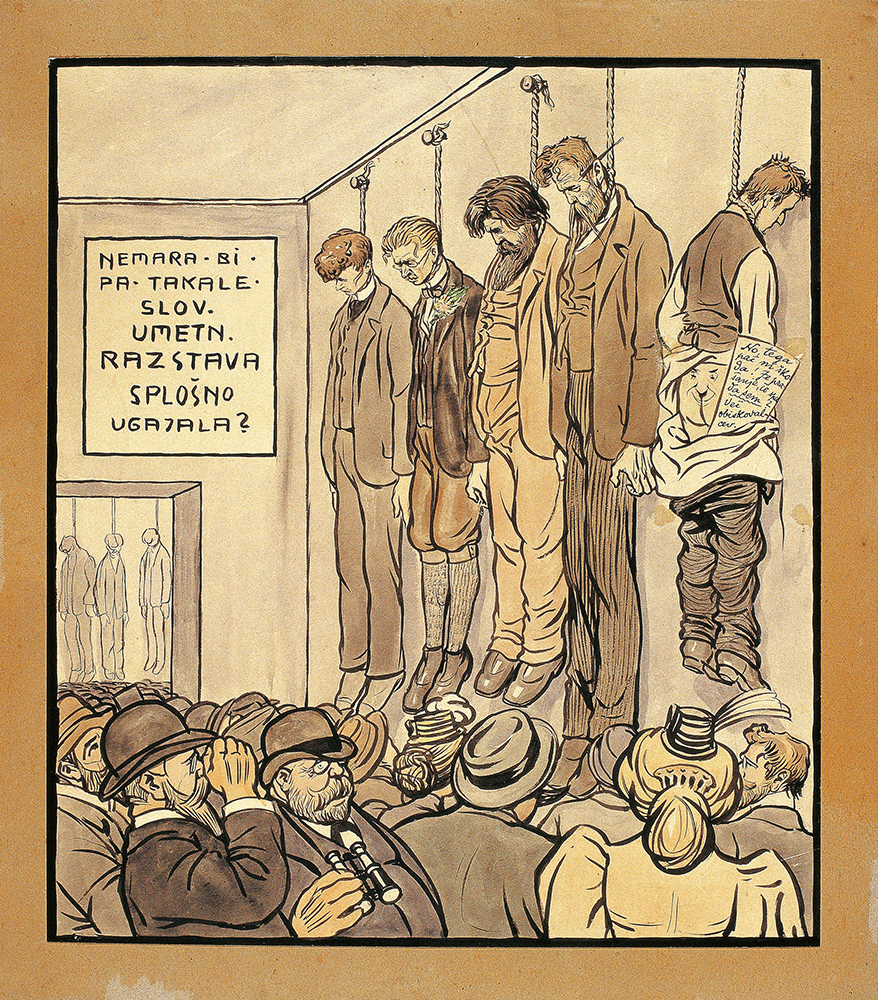

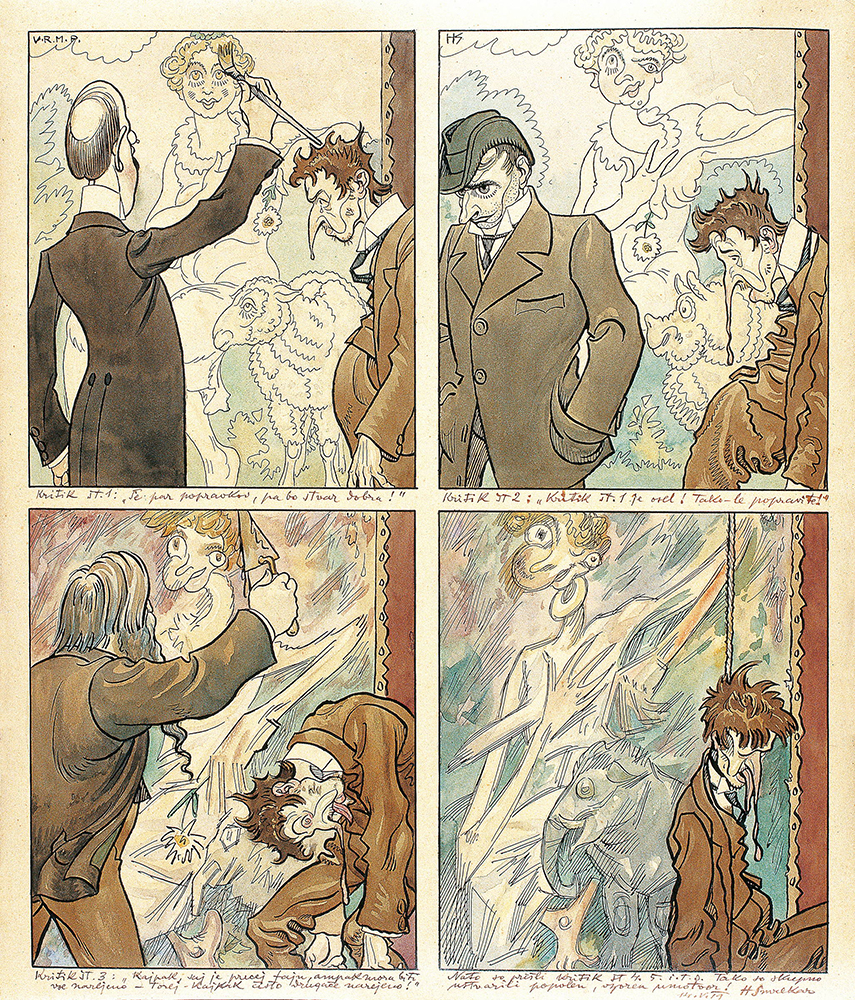

Smrekar’s criticism of provincial society’s attitude towards art, when Ljubljana was asking itself whether or not it was worth going to exhibitions of “young” artists, undoubtedly reached its peak in the satirical drawing The Slovenian Art Exhibition (c. 1910, cat. no. 230). The event is set in Jakopič’s Pavilion, with an exhibit consisting of a row of hanged artists. From left to right: the sculptor Svitoslav Peruzzi, the painters Maksim Gaspari, Rihard Jakopič, Ivan Grohar, and finally Smrekar himself. Next to them a large notice reads: “Perhaps such a Slovenian art exhibition would be generally popular?” Smrekar hangs with his back to the viewing public, his trousers pulled down to reveal his naked posterior — on which an impish face is drawn. A sheet of paper tucked into his trousers bears the message: “Well, there’s no harm in that! What’s it doing here? More visitors.” Smrekar addressed the superficial and often unjustified criticism of his works in Caricature of Four Critics (1919, cat. no. 736), in which critics are seen taking it in turns to make corrections and adjustments to one of his works. As they do so, they change the appearance both of the work and of Smrekar himself, until nothing of either remains. Smrekar was fond of saying that politics and art criticism were two occupations for which one did not need any proof of ability. (Fig. 11)

Fig. 10

The Slovenian Art Exhibition, (c. 1910), National Gallery of Slovenia

Fig. 11

Caricature of Four Critics, (1919), National Gallery of Slovenia

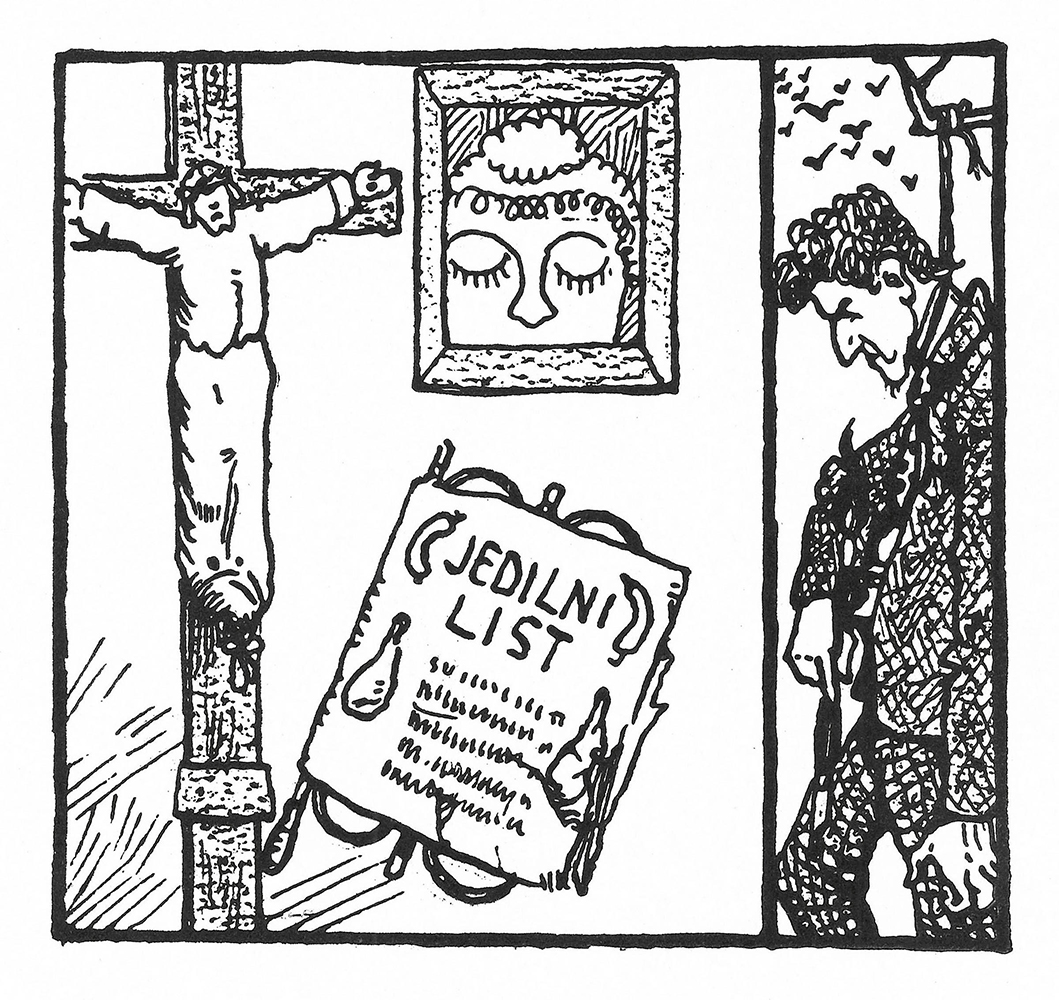

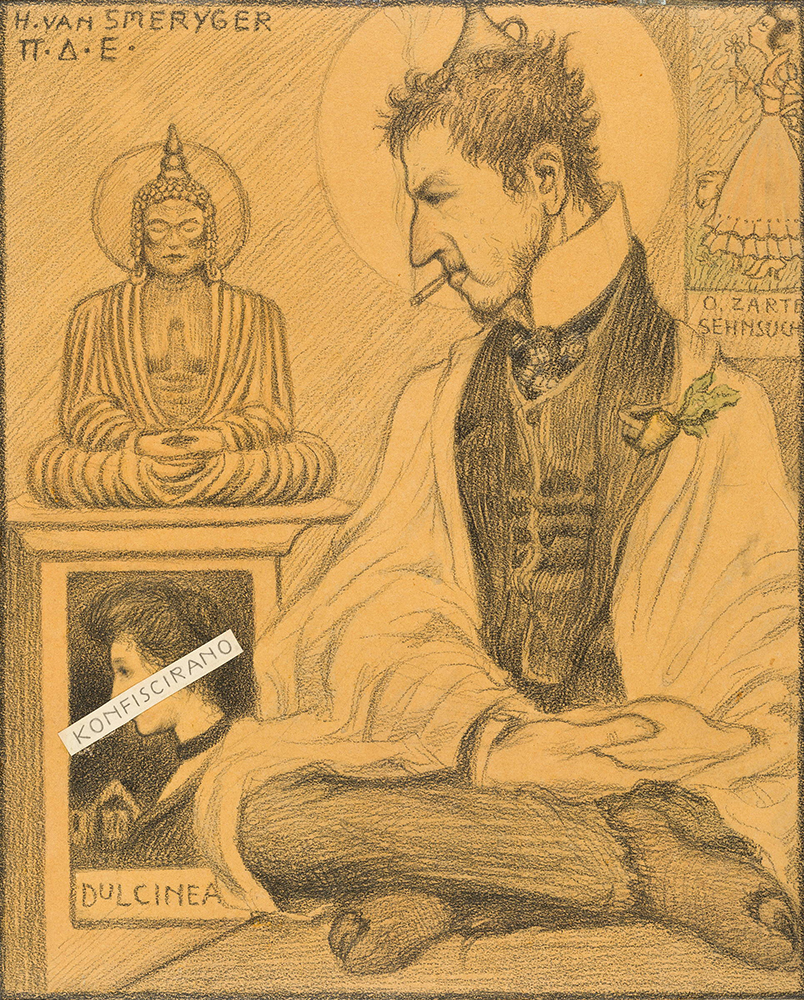

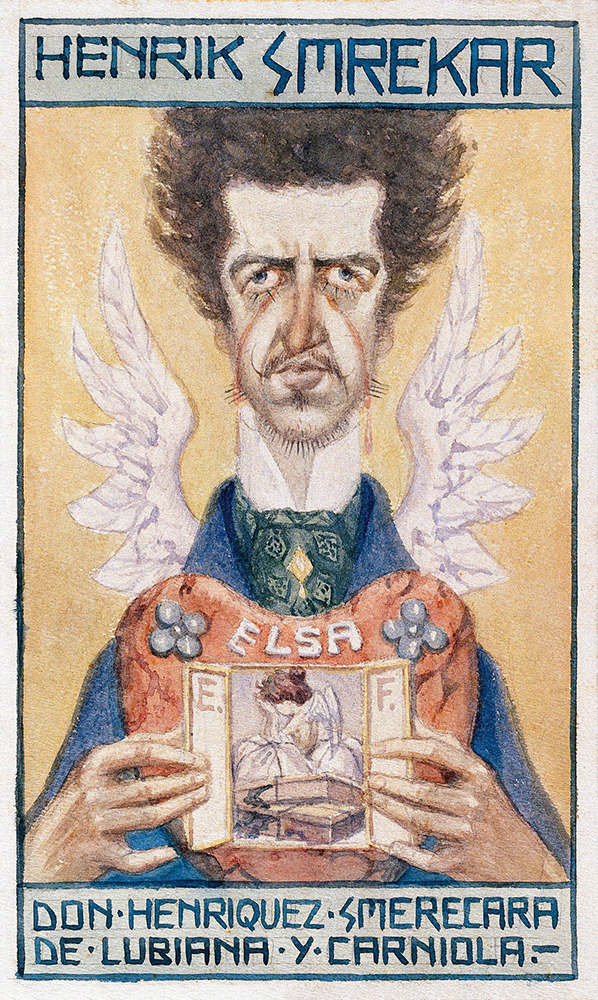

Next come images in all imaginable guises: mischievous in a fashionable lady’s gown, with a bottle in his hand and a coil of excrement on his head – another of his signatures; as Buddha with a halo round his head, a cigarette in his mouth and portraits of two of his lost loves in the background; rueful with angel’s wings and a large gingerbread heart inscribed with the name Elsa – such hearts were given as wedding gifts or as a stand-in for the tender words exchanged by sweethearts; or in a monk’s cowl shedding tears of blood – or cviček wine – out of grief for his fellow citizens. (Fig. 12, 13, 14, 15)

In 1908 the artist produced a serious and carefully wrought self-portrait in a style he would not return to until thirty years later. In it, Smrekar depicts himself in a blue artist’s smock, already visibly weary of the struggles of life. (Fig. 16, 17)

Self-Portrait Playing Cards (1913, cat. no. 406) is one of many popular tavern scenes in which a desperate wife accompanied by her children and her apparently toothless mother implores her husband to come home after he has gambled away all his money. (Fig. 18)

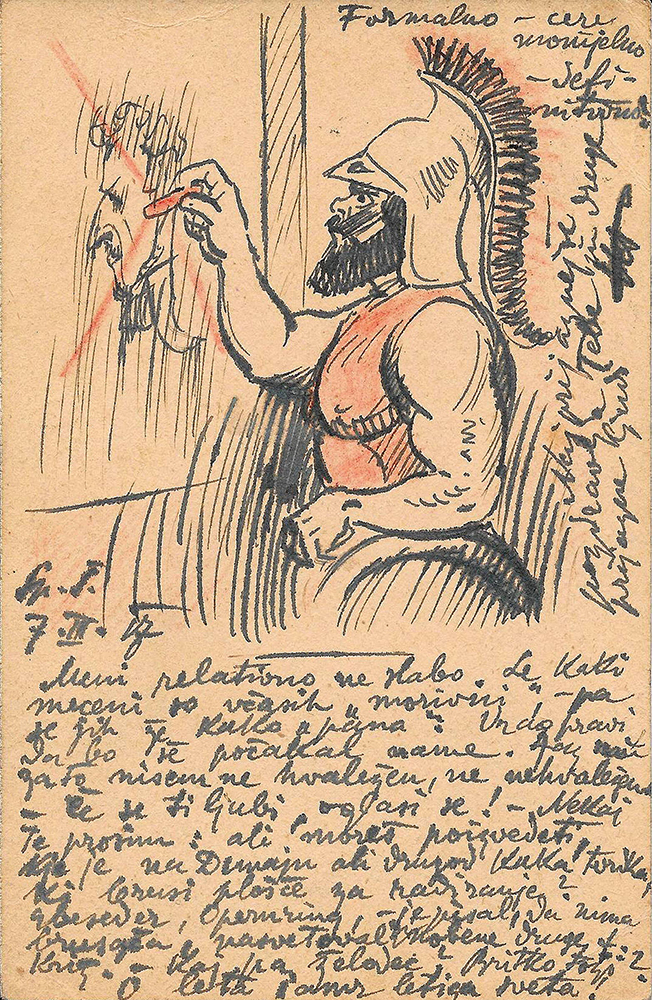

The illustrated autobiography Henrik Smrekar – črnovojnik dates from the time of Smrekar’s arrest and internment and was completed in 1917, but not published until after the war (in 1919). It is considered the prototype of the Slovenian comic book. Smrekar celebrated his return home from internment camps in his illustrated postal cards, one of which shows Mars, the god of war, throwing him out of the army by kicking him in the buttocks, while in another Mars crosses out his portrait on a poster on the wall. (Fig. 19, 20)

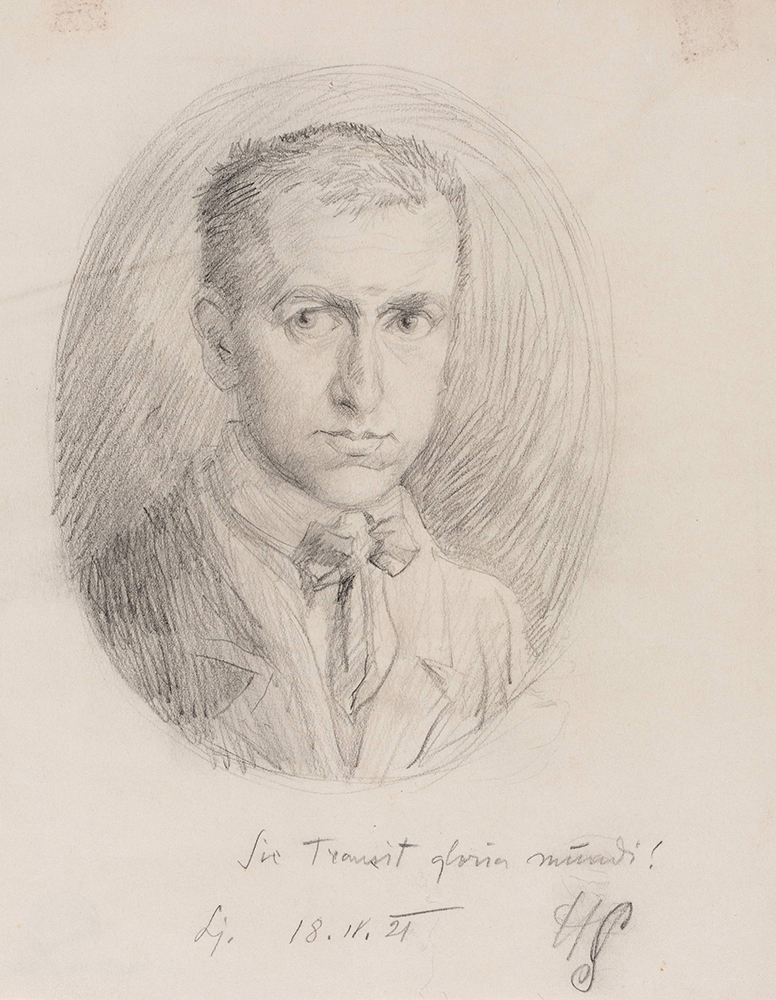

In 1920 and 1921 Smrekar underwent treatment in several health resorts, including Laßnitzhöhe near Graz and Bled in Slovenia. In the latter he stayed at the establishment of Swiss naturopath Arnold Rikli. Despite a creative lull lasting several years, a self-portrait with the inscription Sic transit gloria mundi (Thus passes the glory of the world) and an illustrated postcard showing him strolling along the shore of Lake Bled in fashionable attire survive from this period. (Fig. 21)

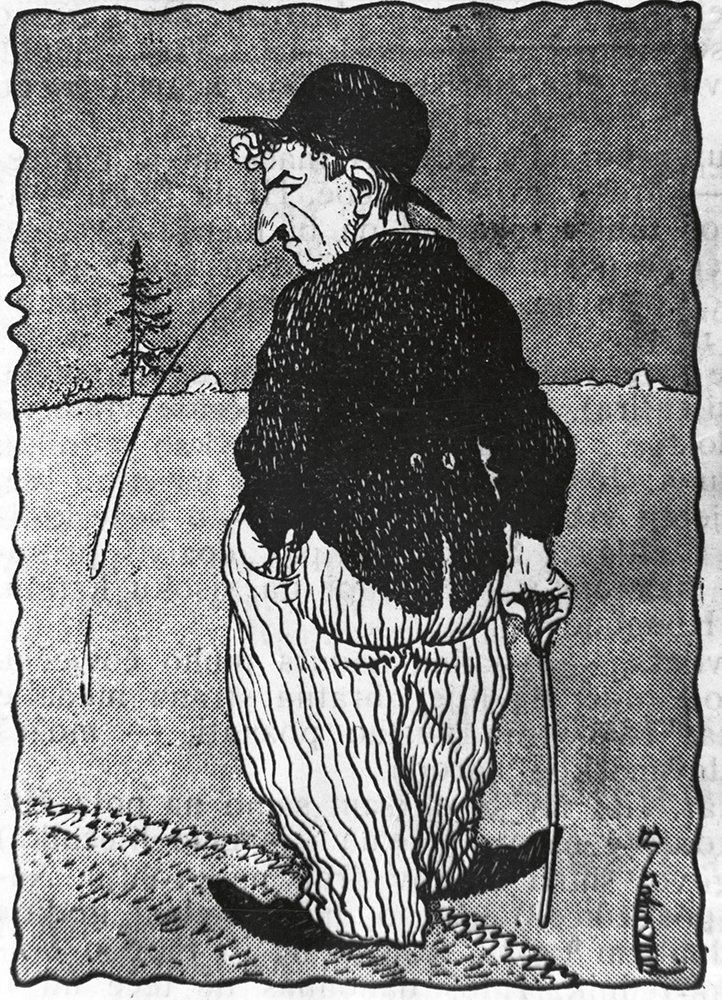

Despite his medical and financial difficulties, he worked with incredible enthusiasm and passion. He took every job that was offered him and collaborated with the widest range of publications. He produced several hundred political and social satires and caricatures, in which he frequently included himself as one of the characters, such as those for the Zagreb satirical newspaper Koprive (Nettles) (1927–1932), in one of which his powerful sneeze is enough to blow the clothes of young ladies, while in another he can be seen demonstrating cooling devices for use during summer heatwaves. (Figs 22, 23) The most noteworthy of the caricatures is the unfortunately lost Self-Caricature as Charlie Chaplin (1931, cat. no. 1136), which accompanied Smrekar’s autobiography in the magazine Naša knjiga, published in Novi Sad. This article is the source of two often cited quotes by Smrekar: “I, Hinko Smrekar, by the grace of God the eccentric-clown of the Slovenian nation…” and “Since Ivan Cankar’s death I feel as though I am only half alive.” (Fig. 24) He also depicted himself as member of a jury in a beauty competition. Another individual to commit his memories of Smrekar to paper was the writer, dramatist and essayist Vladimir Bartol (1903—1967: “He was of medium build, with fine, slender limbs and a slightly protruding, sagging belly of the kind frequently seen in maturer individuals of asthenic constitution. (Fig. 25)

In 1936 Smrekar also illustrated his autobiography Moje romantične noči (My Romantic Nights), which was published in Jutro and from which we can learn more about his love “affairs”. (Figs 26, 27)

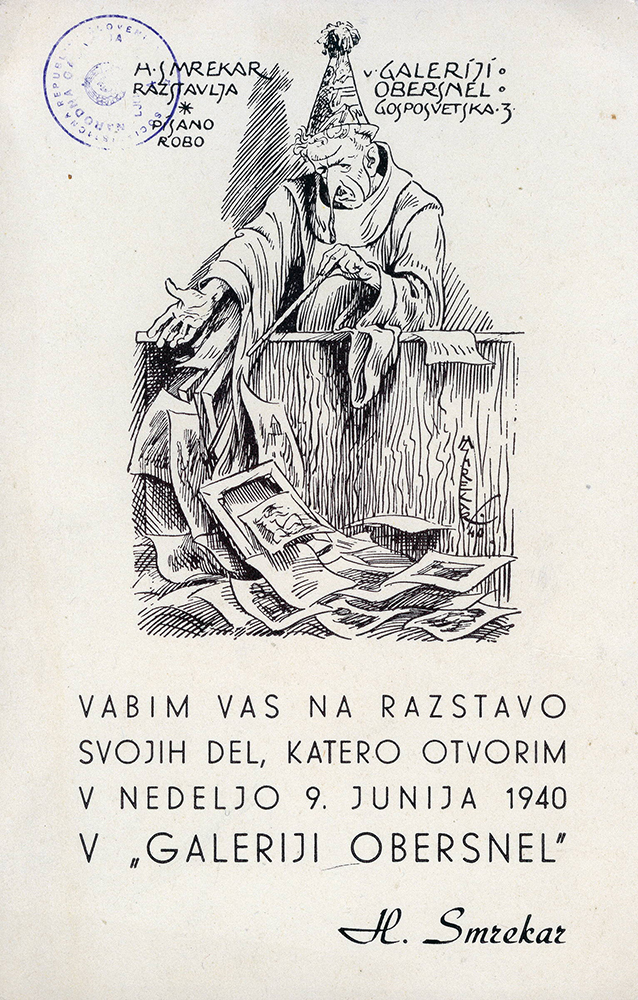

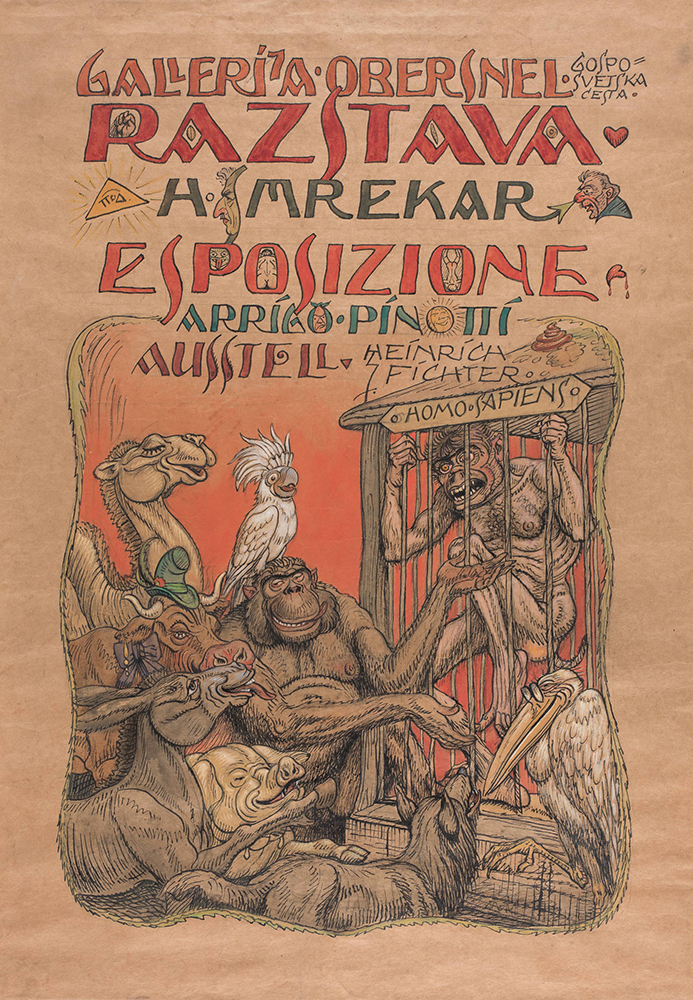

He also included self-portraits in notices and flyers, such as the one for his first solo exhibition at the Obersnel Gallery (1940), in which he describes himself as “exhibiting colourful wares”, or the poster for another exhibition at the same gallery a year later, in which his likeness is hidden among the lettering. (Figs 28, 29)

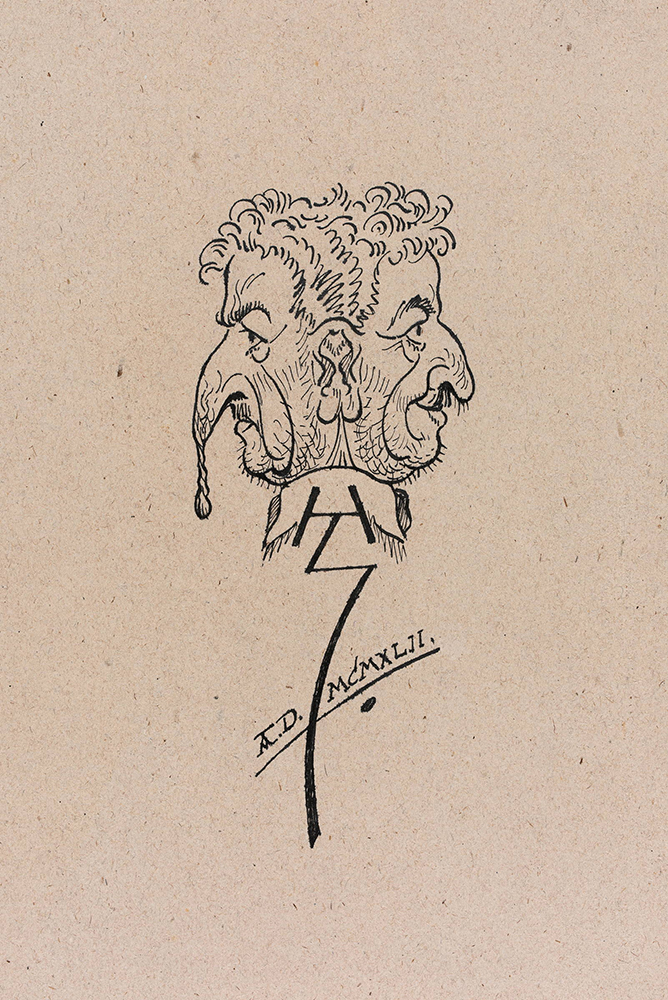

In a self-caricature from 1942 he drew himself with a Janus head, his two faces showing the two sides of his character: the face of a melancholic with a long, drooping nose and the face of a mischievous prankster. The drooping nose with a drop at its end had been a trademark of Smrekar’s ever since 1905, when Ivan Cankar published the short story Povest o dolgem nosu (Tale of a long nose), in which he described or, rather, caricatured Smrekar. The adoption of the Roman god Janus sums up Smrekar’s entire approach to his work, in which he constantly remained true to himself and convinced of the rightness of his actions, regardless of the consequences. The way in which he drew attention through his work to the mistakes and delusions of society connects him to an ancient idea akin to the spirit of Janus, which states that before every action one must look back at the past in order to predict its consequences in the future. (Fig. 30)

Author: dr. Alenka Simončič, 2022