Stories told through multiple pictures are a characteristic element of Hinko Smrekar’s work. It is likely that he first encountered the format abroad, in satirical magazines. These featured extremely high quality illustrations for jokes, short stories and poems and, above all, caricatures and stories told through pictures, sometimes printed in colour.

Pioneer of Comic Strip

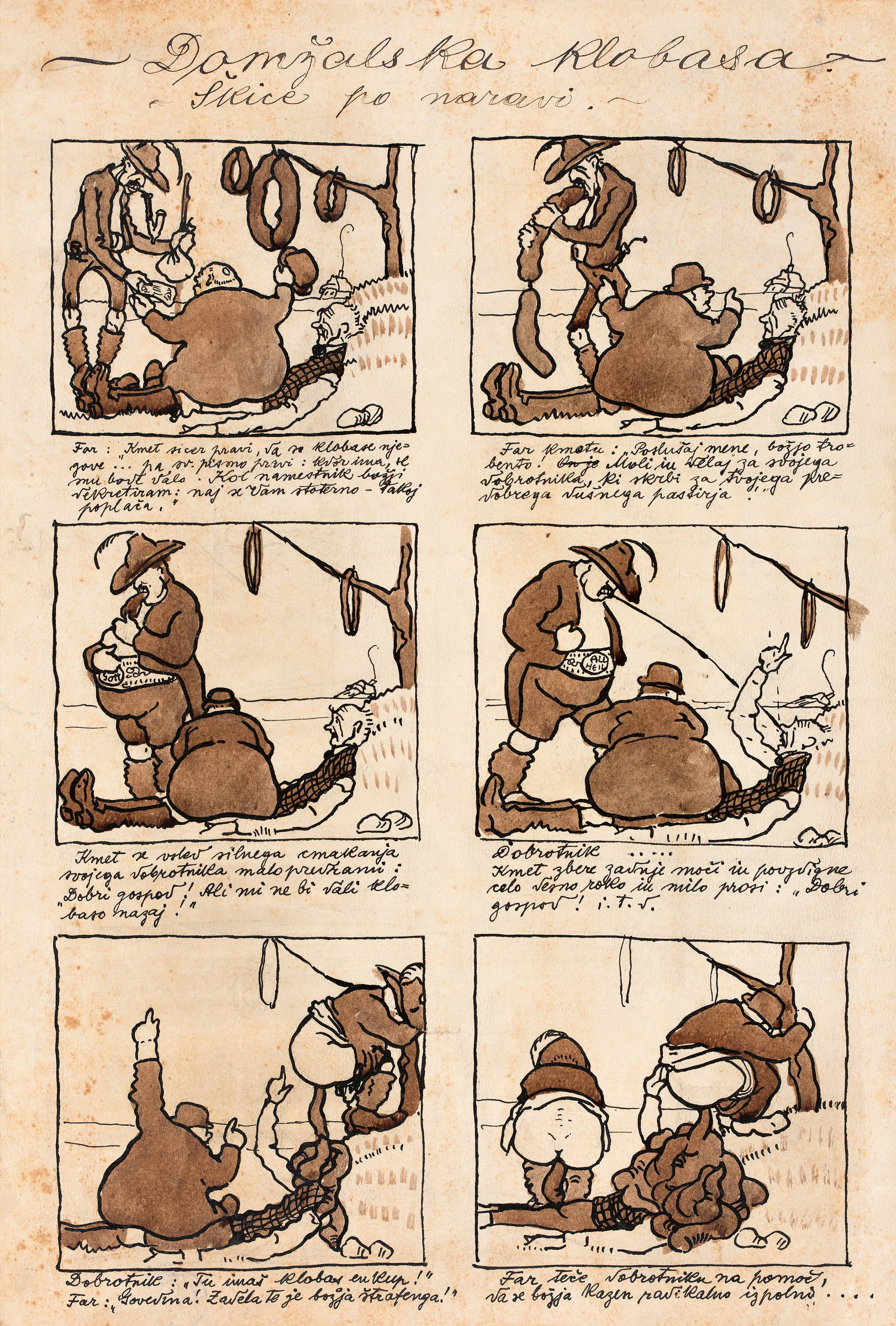

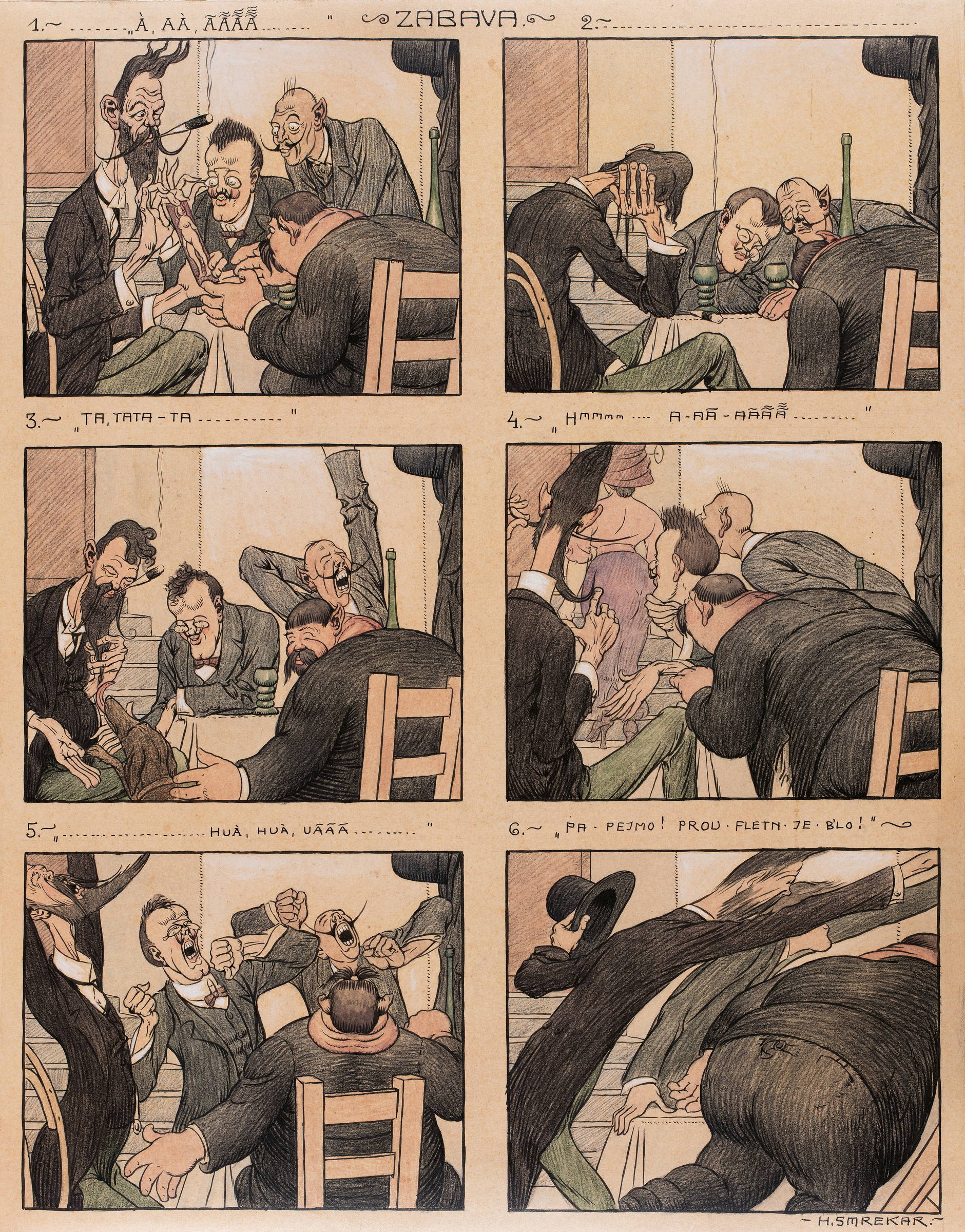

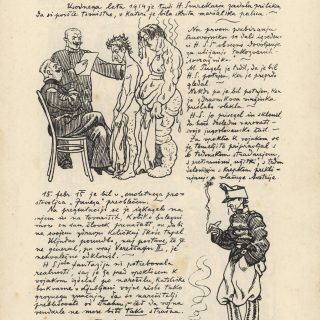

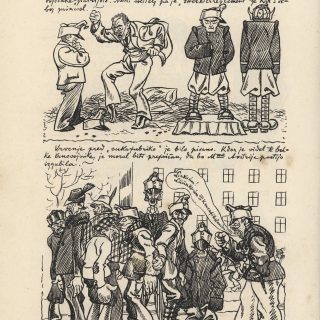

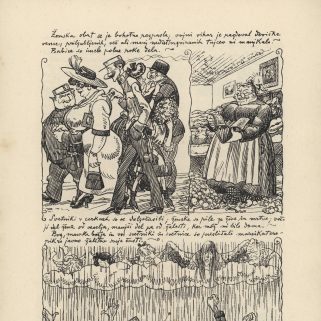

The earliest examples in Smrekar’s oeuvre of drawings following each other in the chronological sequence are the illustrated postcards he used to send to his friends. He would write a story on them and then illustrate it. (Figs 1, 2.) These are followed by illustrations for the satirical newspaper Osa (1906) and a few isolated examples in 1909 and in around 1911 such as Domžale Sausage. Sketches from Nature and The Party. Smrekar exhibited the latter several times, including years later at his first solo exhibition at the Obsersnel Gallery in Ljubljana in 1941. (Figs 3, 4.)

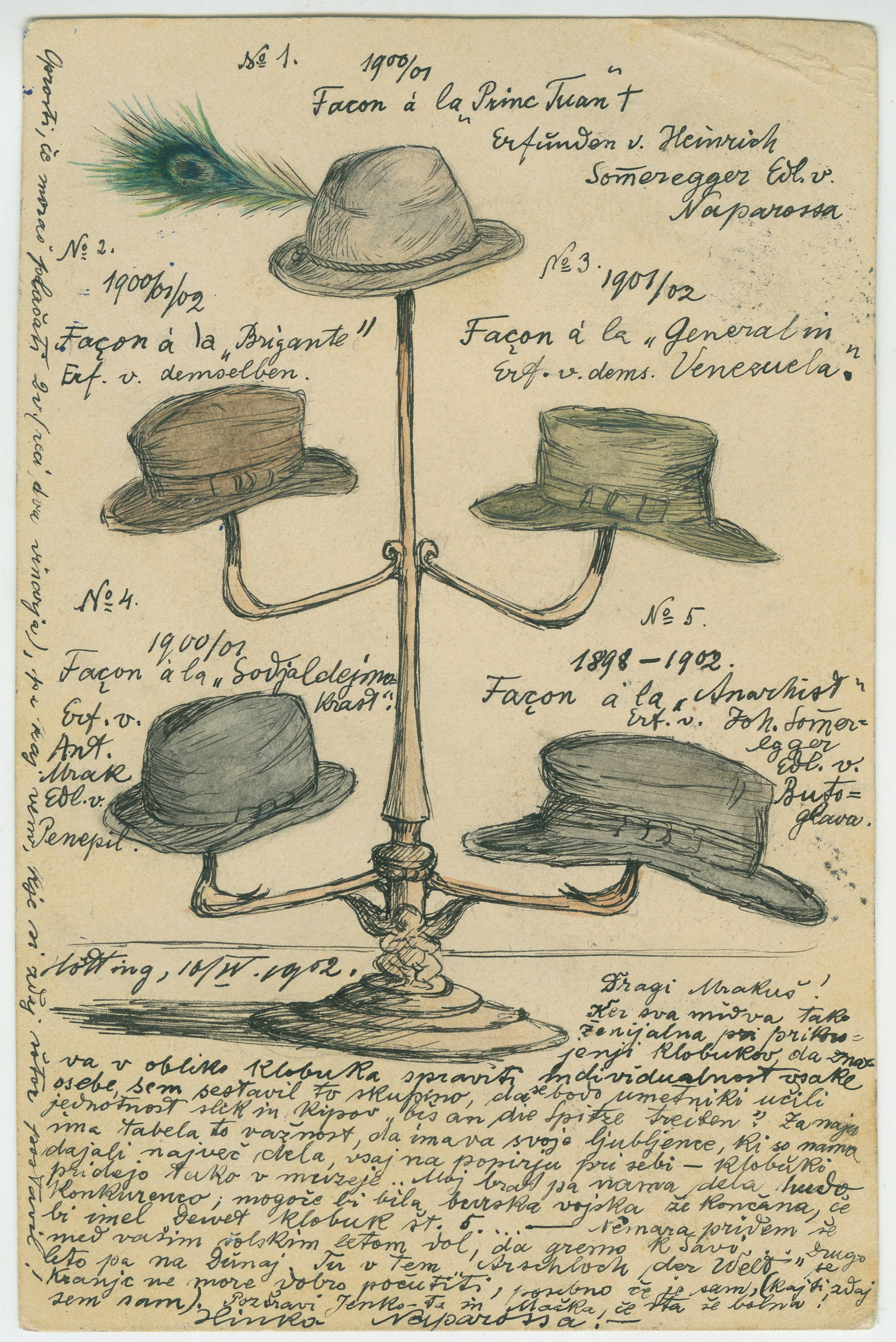

Fig. 1

Hat-Stand, illustrated postal card for Anton Mrak, 1902, National Gallery of Slovenia

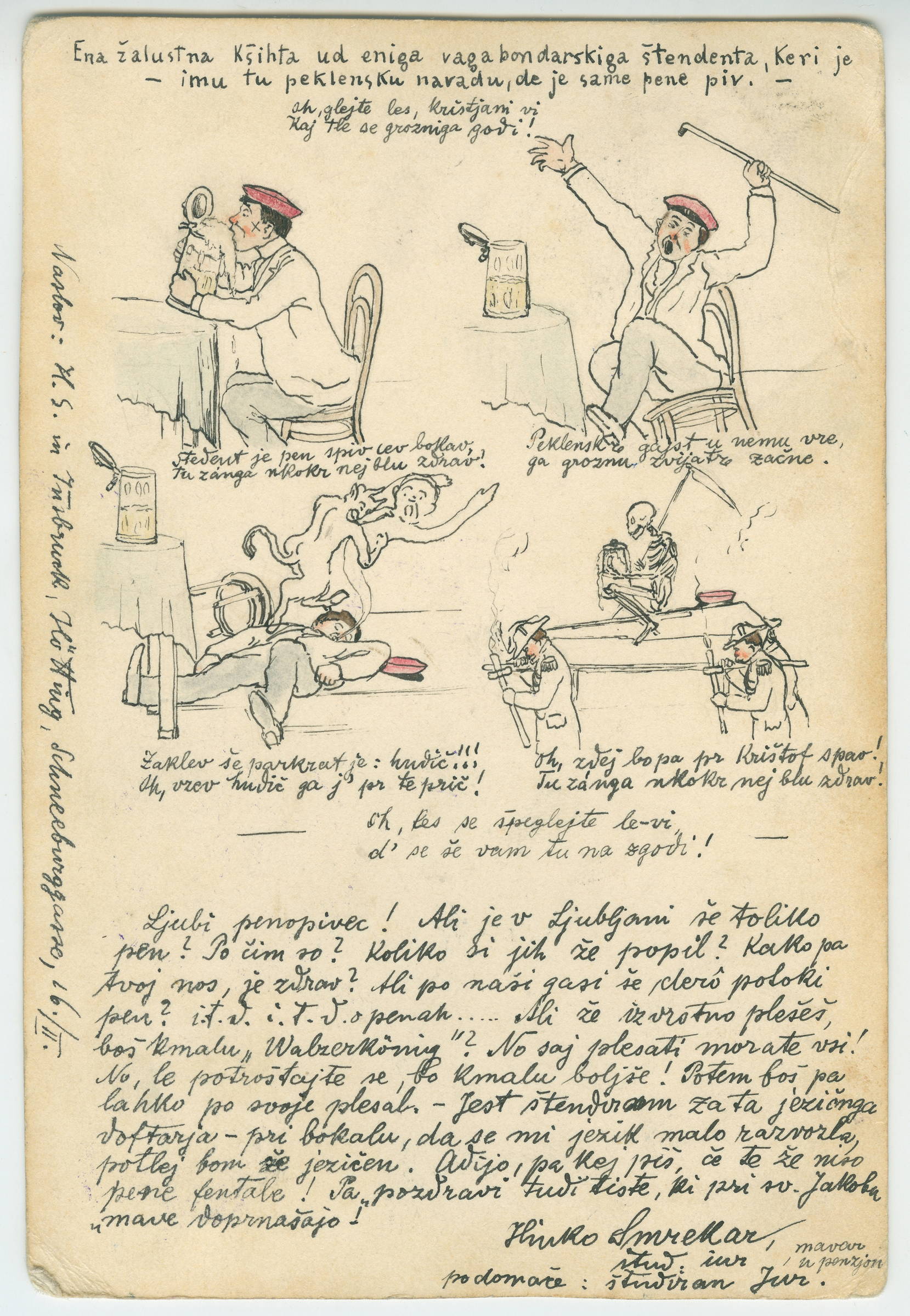

Fig. 2

Story of a Student who Drank Beer Foam, illustrated postal card for Anton Mrak, (1902), National Gallery of Slovenia

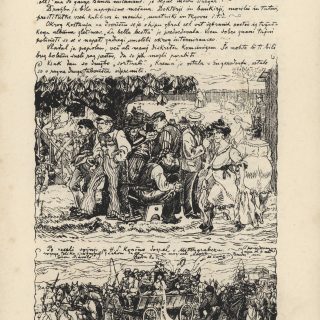

Fig. 3

The Domžale Sausage. Sketches from Nature, (c. 1911) , National Gallery of Slovenia

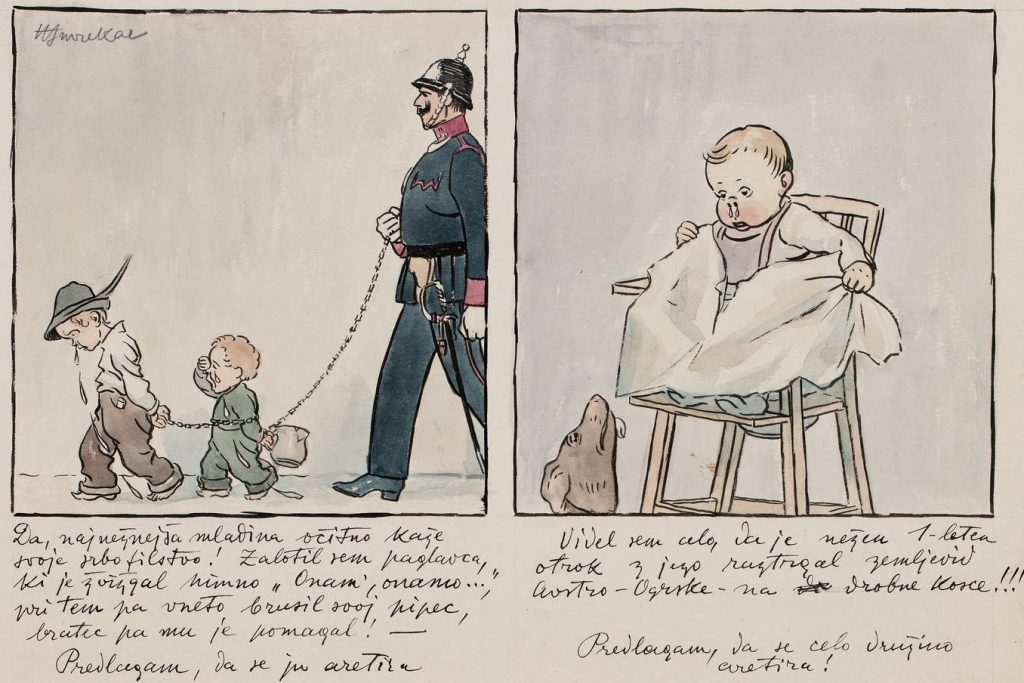

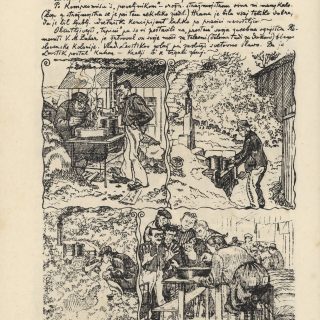

Fig. 4

A Party, (1911), National Gallery of Slovenia

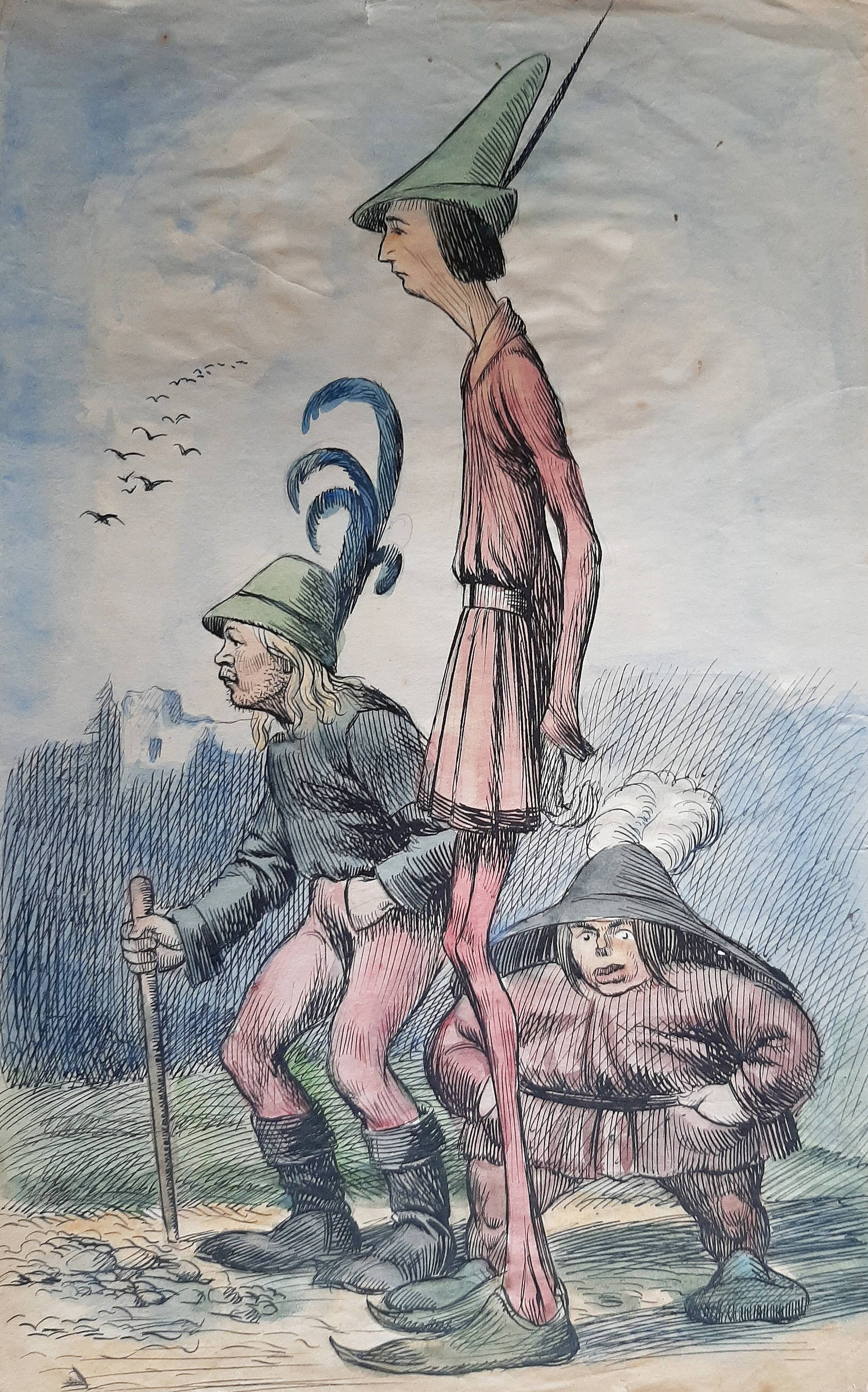

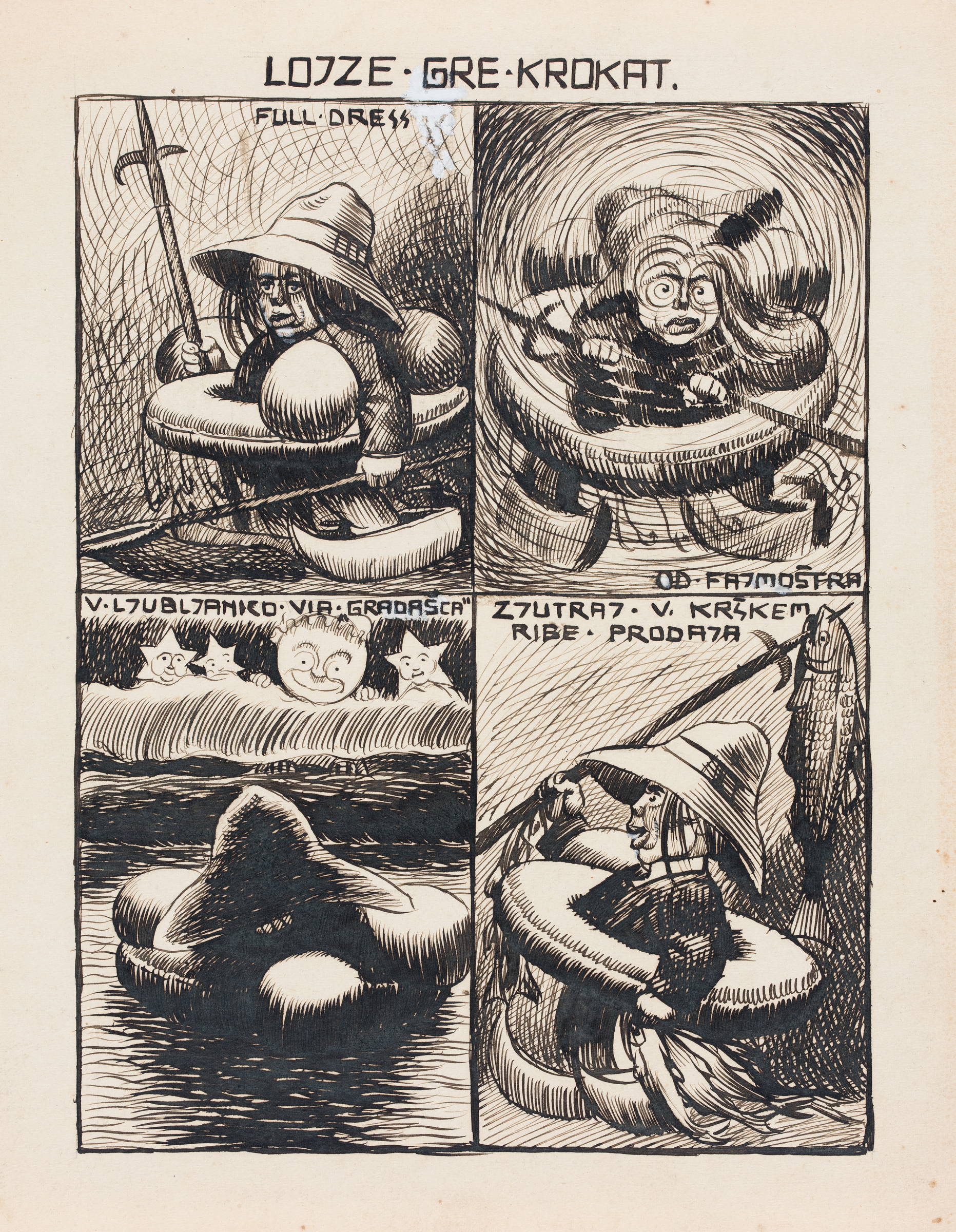

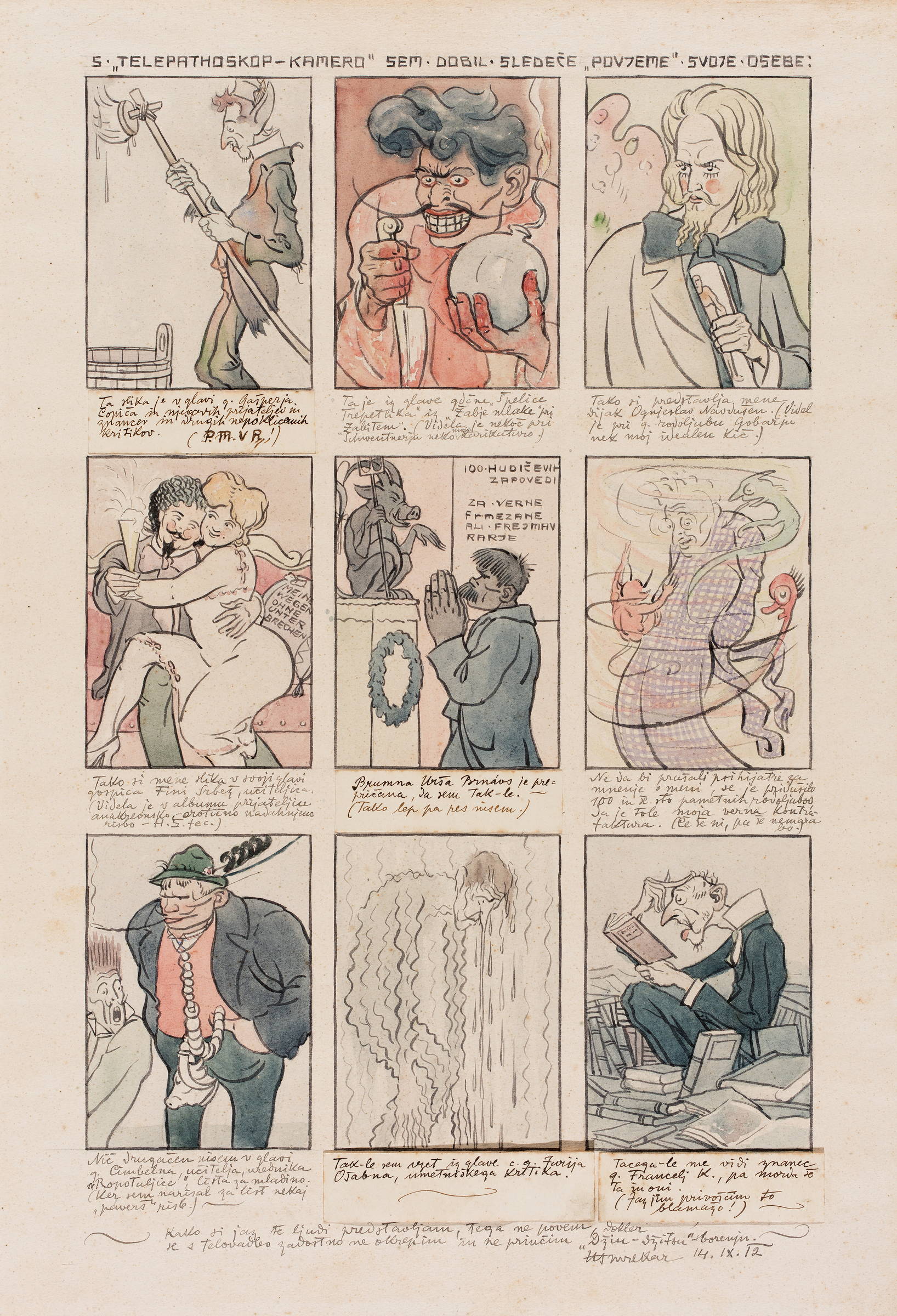

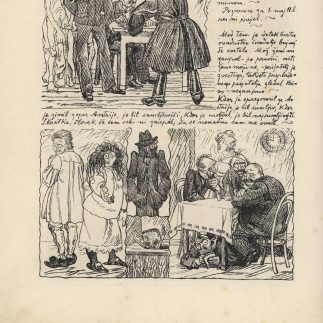

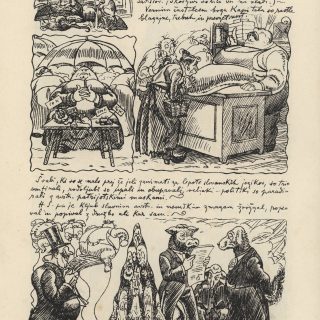

A great lover of fairy tales, Smrekar would occasionally portray one of his colleagues as a fairy-tale character. The sculptor Lojze Dolinar, who was short and tubby, was perfect for this world. We find him as Glutton, one of the heroes of the Slavic fairy tale The Mighty Four, and as the butt of the joke in Lojze’s Night Out. Smrekar caricatured himself in the same manner in the drawing Nine Self-Caricatures with Captions.(Figs 5, 6, 7.)

Fig. 5

Three Fairy-Tale Heroes, (1912), National and University Library of Slovenia, Manuscript Collection, Ljubljana

Fig. 6

Lojze Goes Pub-Crawling, (1912), private collection

Fig. 7

Nine Self-Caricatures with Captions, 1912, National Gallery of Slovenia

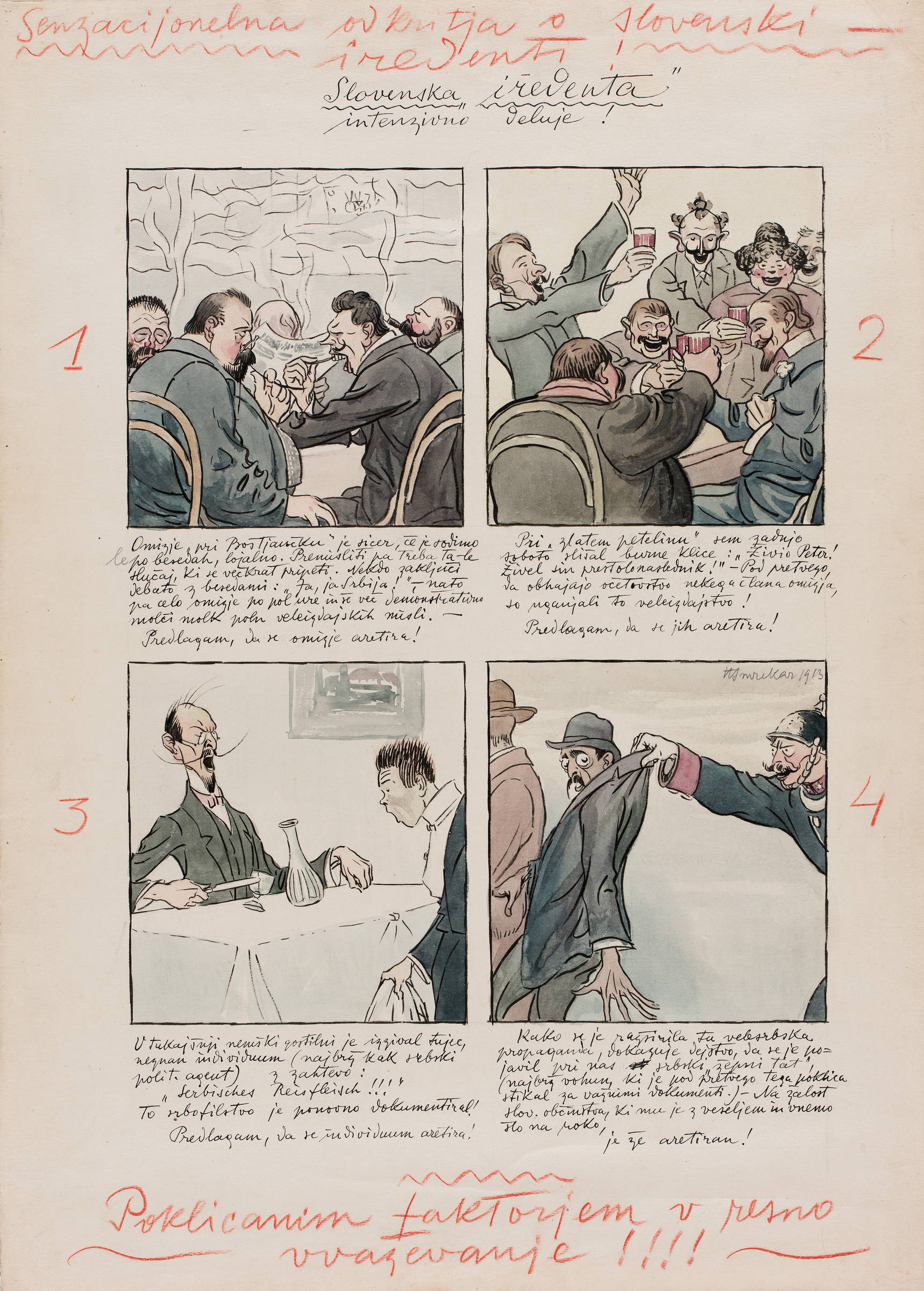

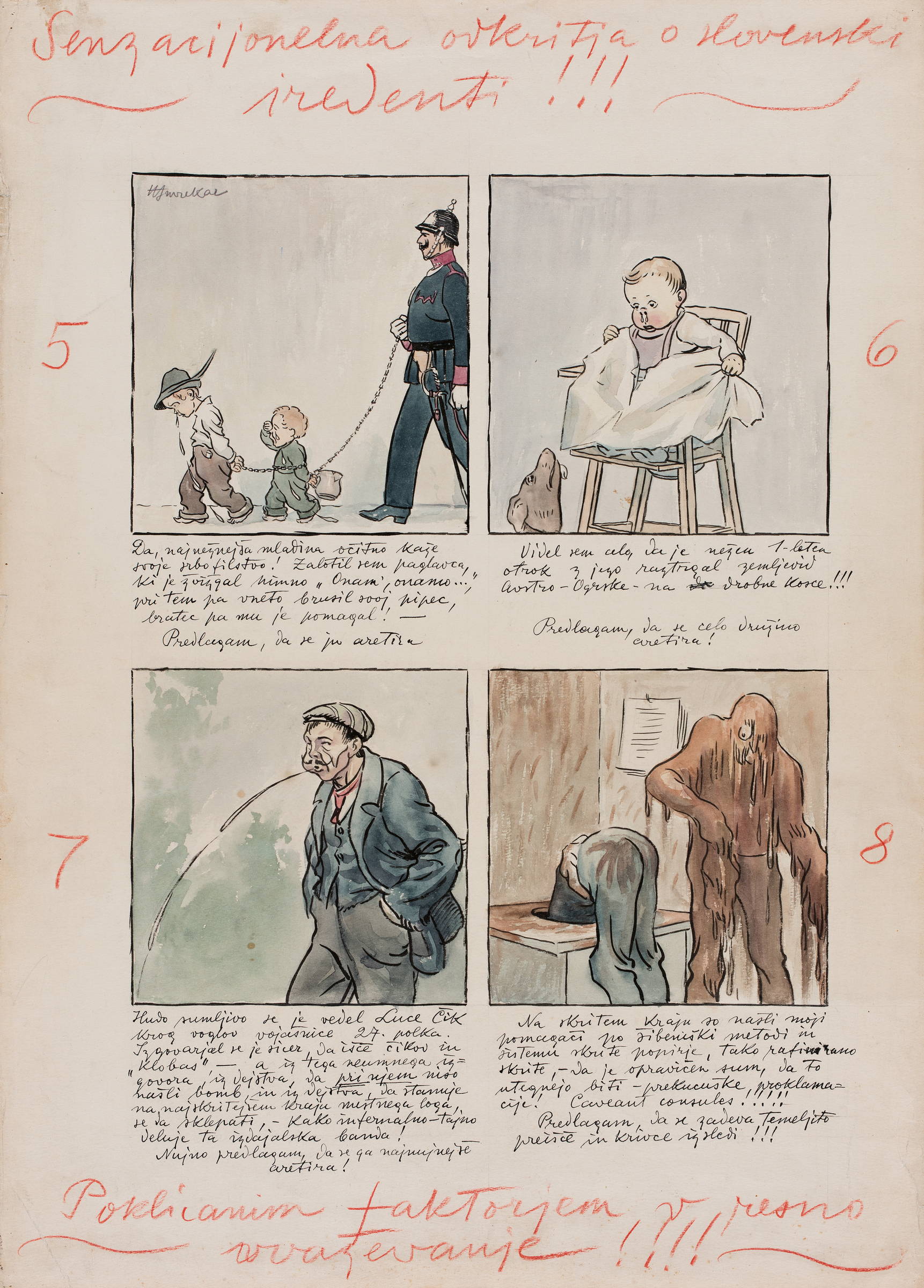

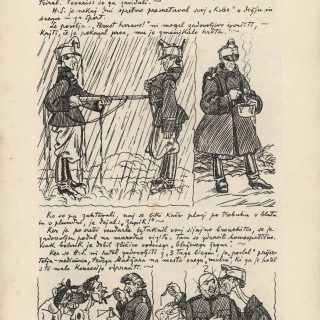

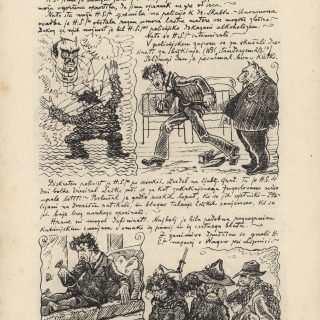

In 1913 he displayed two satirical works entitled Sensational Discoveries of Slovenian Irredentism (cat. nos. 417, 418) in Lavoslav Schwentner’s window, subtitling them “for the consideration of the responsible agents”. Eight panels show different “traitors”, such as a baby tearing a map of Austria-Hungary or a man in a tavern yawning “Ah, Serbia”. The drawings were removed the day after they were displayed. (Fig. 8, 9.)

Fig. 8

Sensational Discoveries of Slovenian Irredentism I, 1913, National Gallery of Slovenia

Fig. 9

Sensational Discoveries of Slovenian Irredentism II, (1913), National Gallery of Slovenia

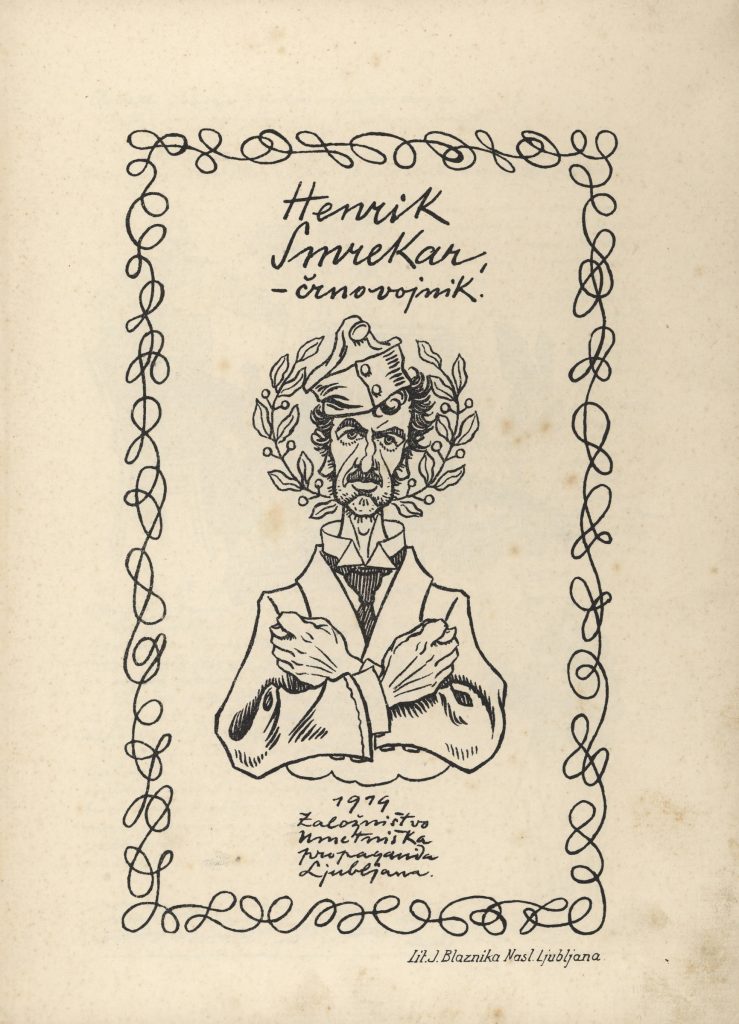

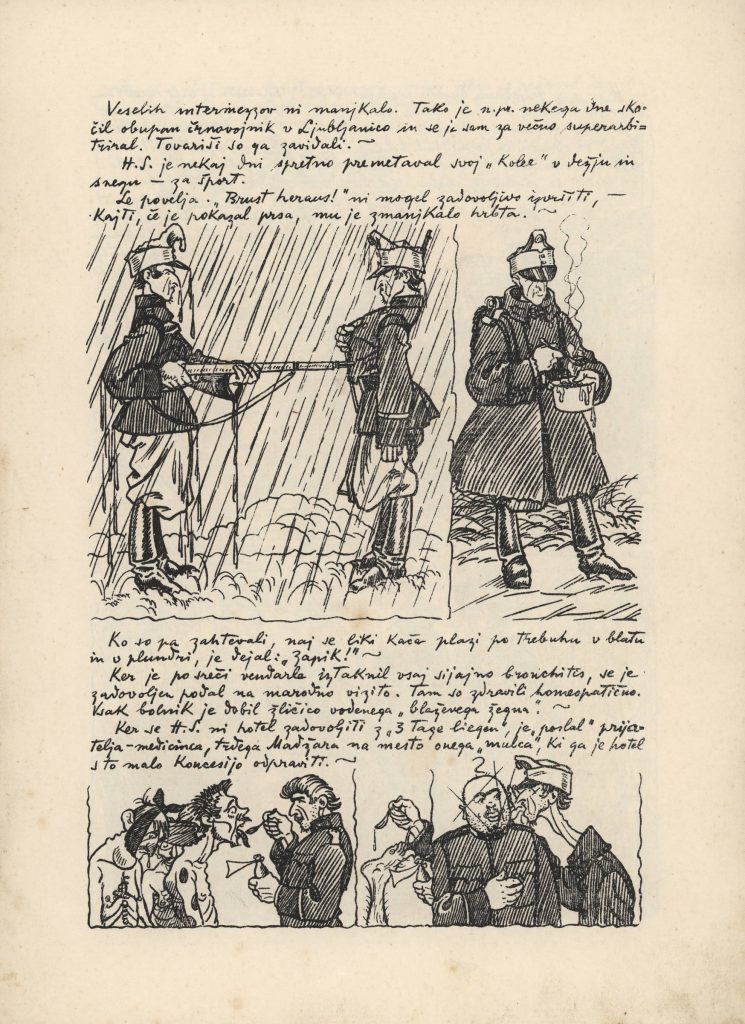

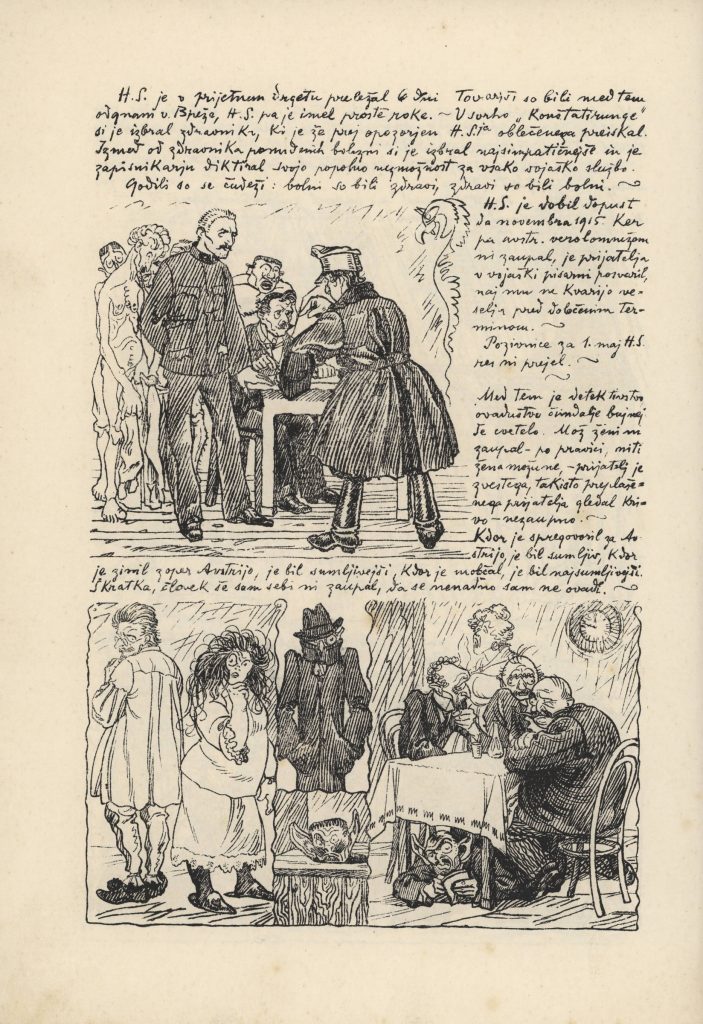

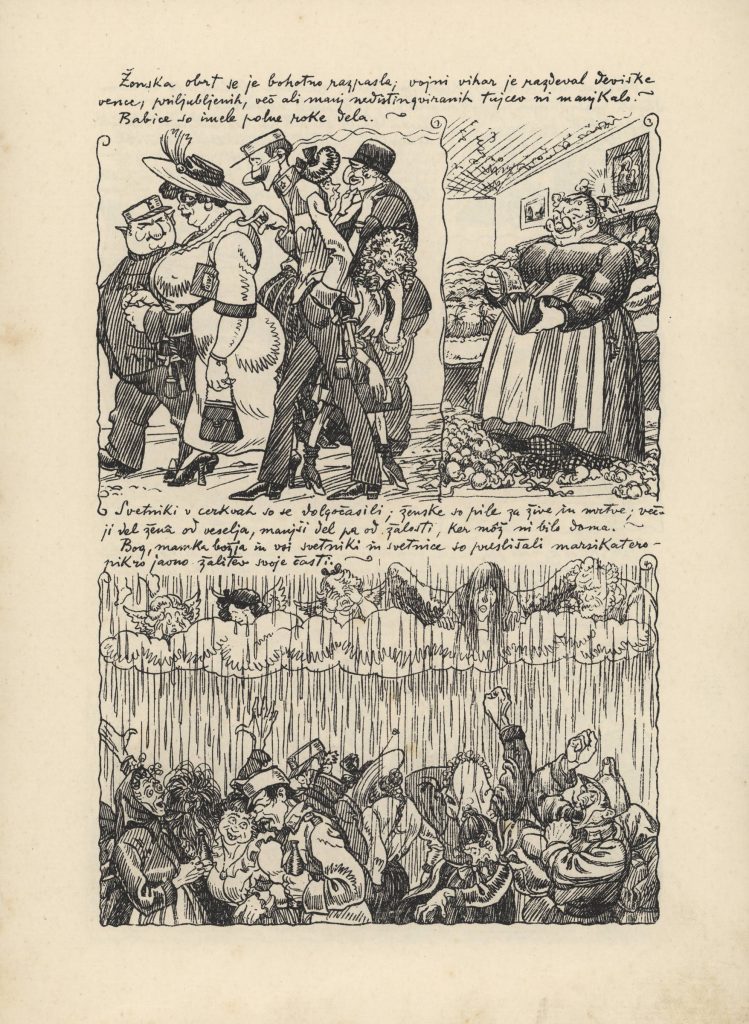

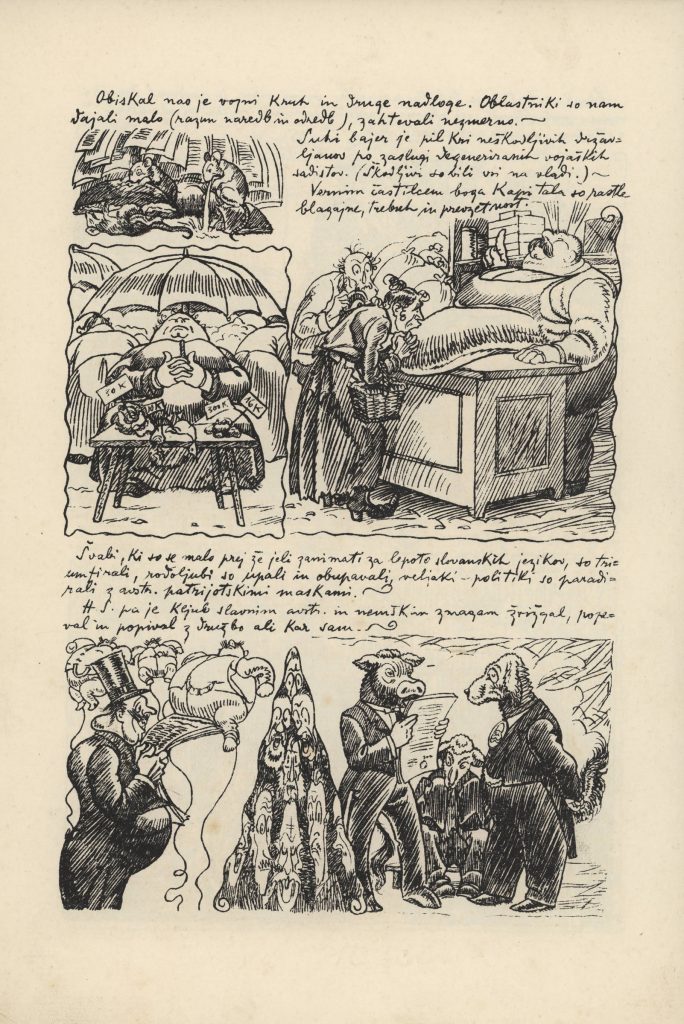

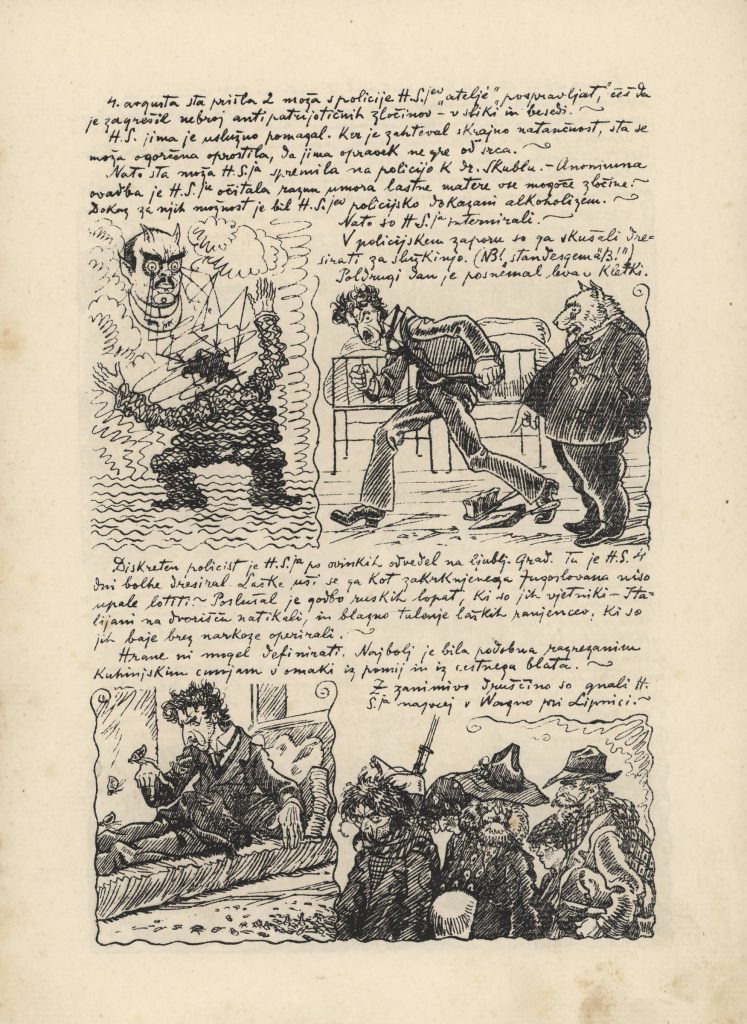

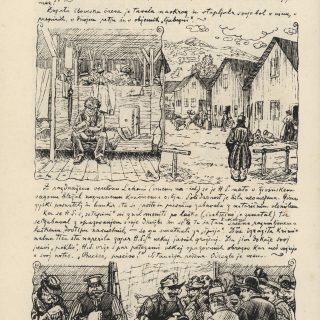

Henrik Smrekar – the Landsturm Soldier

The year 1915 was without a doubt a turning point in Smrekar’s life. This was the year he was arrested following an anonymous denunciation and taken off to various prisons and camps. An insight into this period of Smrekar’s life is provided by the satirical yet poignant illustrated autobiography Henrik Smrekar – črnovojnik (Henrik Smrekar, Landsturm soldier), which he had already written and drawn in 1917, but which was not published until after the war (1919). It is considered the prototype of the Slovene comic strip.

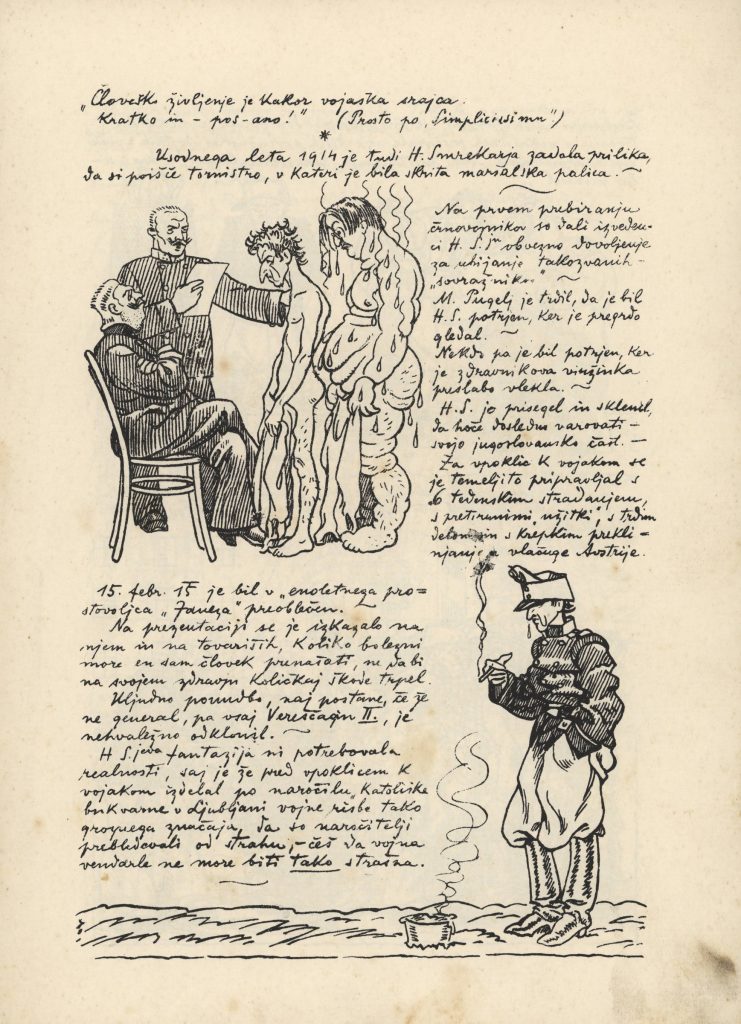

Forming the basis for the autobiography were the events of early 1915, when Smrekar was called up to the reserves but avoided having to join his unit by convincing the military assessment board to place him on leave until November of that year.

The ensuing anonymous denunciation, sent to the imperial and royal military command in Graz, had a fateful effect on Smrekar. In early August 1915 he wrote to his mother: “Dear Mother! Serious charges have been brought against me. I have been detained in prison — I will be interned as a ‘dangerous person’. So my freedom has been taken from me, there is nothing worse, but do not fear, do not be afraid.” Since the denunciation is important for understanding the state of society at that time, we reproduce it here in its entirety:

“The academy-trained painter Heinrich Smrekar, currently residing at Spodnja Šiška no. 136, who reported for the assessment of his fitness for military service and who served for a few weeks in the spring, managed skilfully to avoid it, claiming that he was suffering from various illnesses, until he was sent on leave until November.

Before the respectable and courageous officers and the military officer corps Smrekar, an ardent admirer of Serbs and Russians, made the following statements in Slovenian: All our officers, from First General down to the last Lieutenant, are fools and are unworthy of even being starved with a diet of bread and water. The stupidity of military doctors, especially Staff Doctor Geduldiger in Ljubljana, is such that they hear the grass growing and have no idea about anything, otherwise they would not have sent me on leave. In order to avoid service, I swallowed chalk and drank a lot of black coffee, which caused me to appear very unwell, so I was declared ill and unfit for military service by these monkeys from the regiment. In a certain company, Smrekar repeatedly said that Carniola, Croatia, Bosnia, Dalmatia and the like would soon become Serbian territory, and that a real government would be established as soon as these lands were free of the Austrian-German barbarians and joined their Slavic brothers.

Furthermore, he often sings and whistles Serbian songs, the Marseillaise and similar inimical nonsense, he rejoiced at our defeats in Belgrade and Przemyśl, he praises on every occasion Russian and Serbian victories, and much else, too much to record here.

Every night, he wanders around until 3 am, patronising the inns and cafés sympathetic to the Serbs, especially the Café Evropa in Ljubljana, also known as Café Beograd, and returns home late at night completely drunk and causing disorder.

Smrekar also made many derogatory statements about the war bonds and ridiculed various persons, asking whether they might not have some money to squander, since Austria was about to break up.

At the patriotic rally of the metalworkers, he shouted and roared that people are stupid to give anything at all so that the war, which Austria had unjustly started, could continue.

He is also friends with Milan Zimmerman, the first reservist of the 20th Military Police Battalion, and much more dangerous than the latter. There are many witnesses who could confirm these claims, but unfortunately they are all Serbophiles, Russophiles and Slovenian liberals, who would not testify against him. There are also others who fear giving a statement, or are not able to for business or similar reasons, because it would be disastrous for them.

We regret that this criminal cannot be brought to justice on the basis of solid evidence. We ask you to give this scoundrel a thorough medical examination, for if he can drink and stay up all night, there must be a job for him in the army. Your Excellence, we assure you that he is not at all ill but perfectly healthy.

I apologise for writing anonymously, but I am not able to do otherwise for various reasons.

An Austrian patriot, formerly an obedient, disciplined soldier, admirer of our beautiful dynasty, our exceptionally brave military corps, and our loyal federal brethren.

Long live Austria and Germany!”

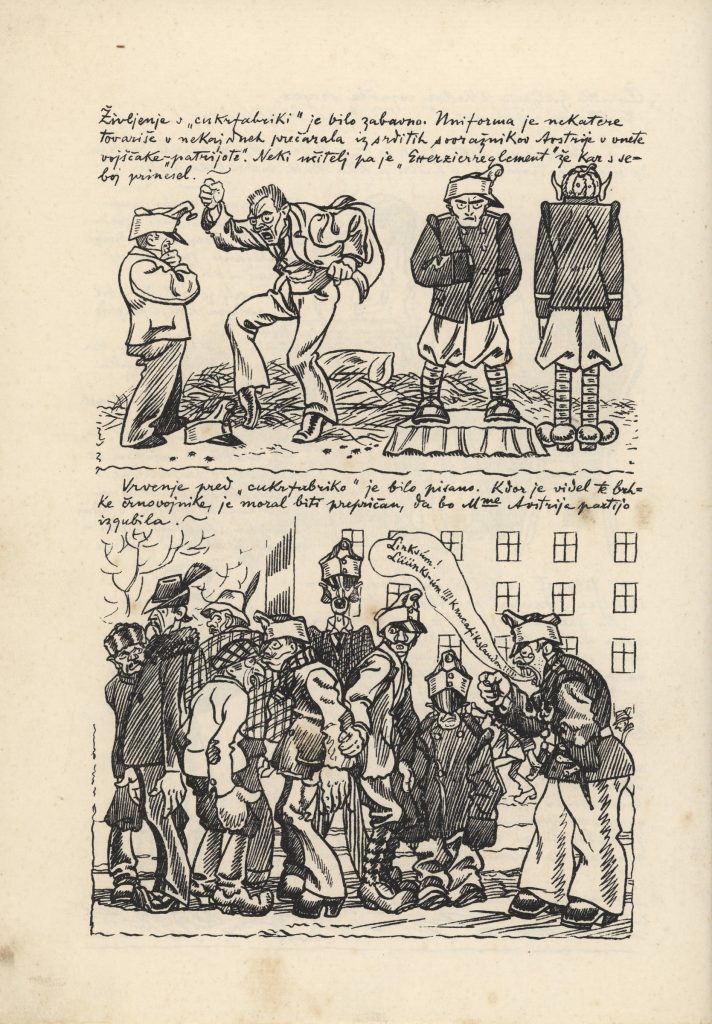

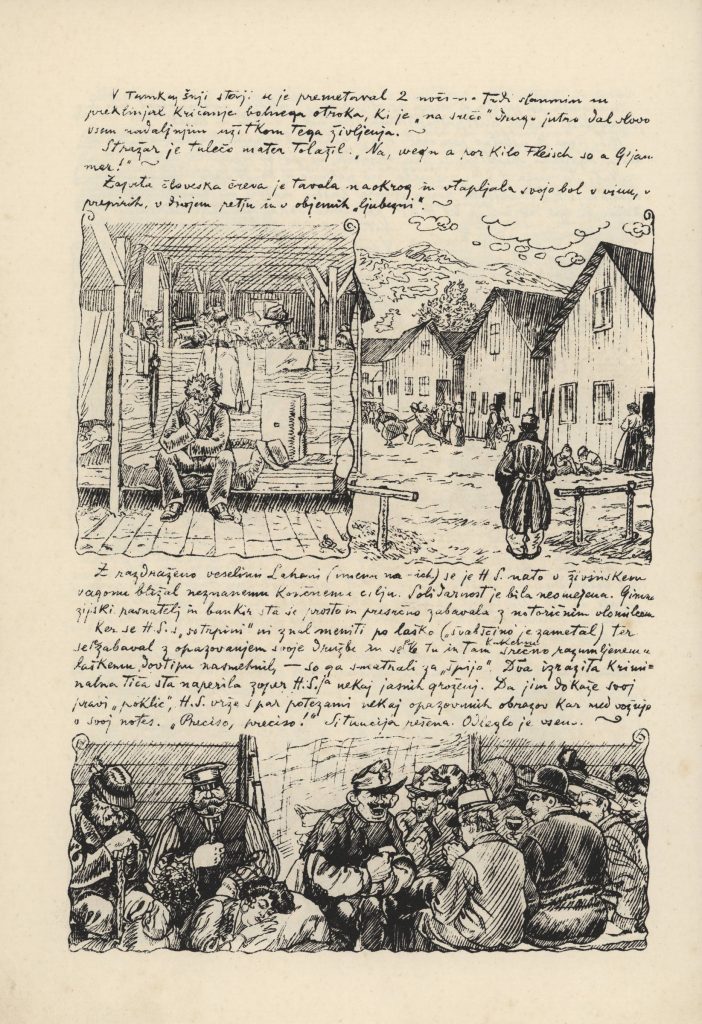

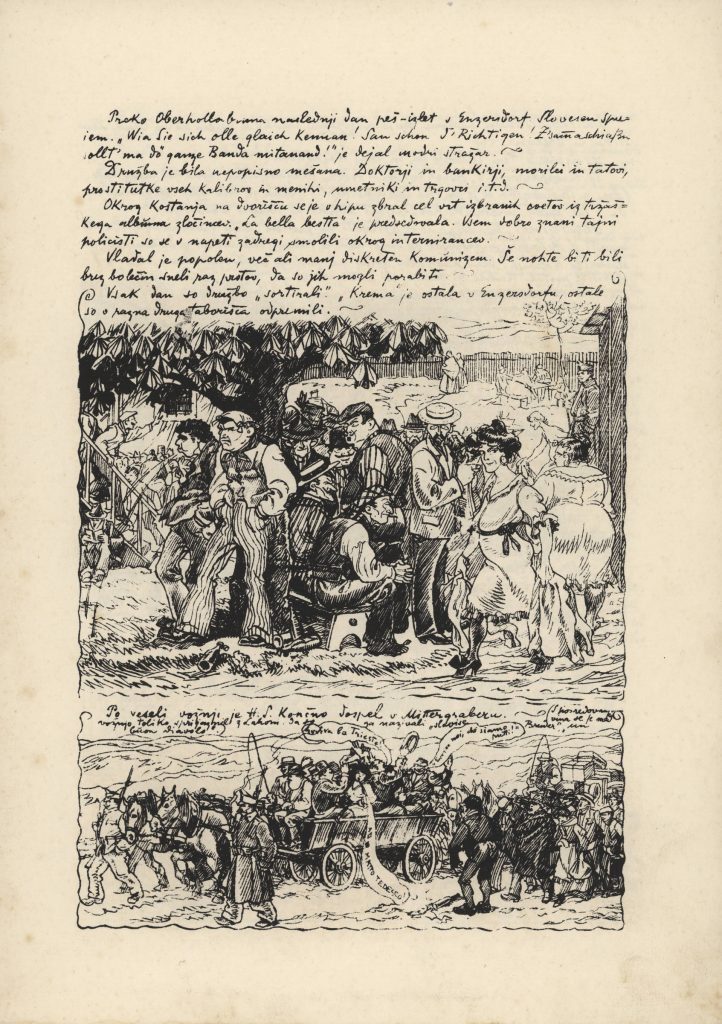

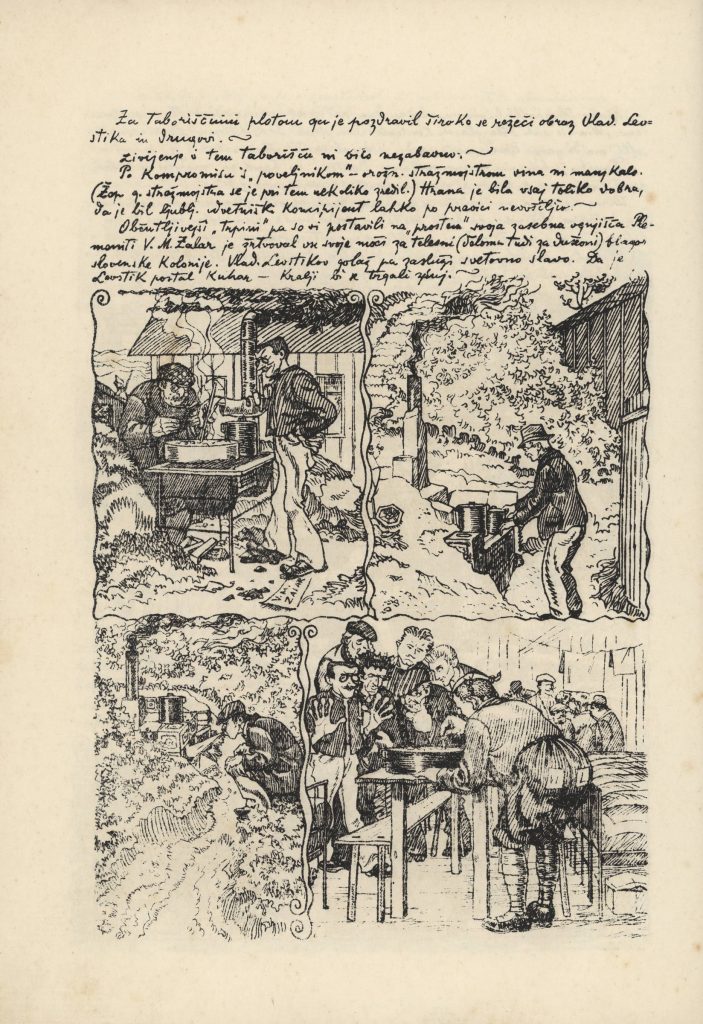

Smrekar was initially held in the police cells at the court and then transferred to the prison in Ljubljana Castle. A few days after that he was taken to a camp at Wagna near Leibnitz, and then to Enzersdorf in Lower Austria and the internment camp for politically suspect citizens in Mittergrabern. Smrekar met several of his friends there: writers Vladimir Levstik and Ivan Lah, editor of Slovenski narod Rasto Pustoslemšek (1915), writer Viktor M. Zalar (aka. Amba) and folk poet from Vipava Fran Žgur. Smrekar remained in Mittergrabern for just over a month and then received his call-up papers for a second time, whereupon he was taken to Judenburg in Upper Styria for his medical. Judenburg was where the replacement battalions of the Imperial-Royal 17th Infantry Regiment, nicknamed the Kranjski Janezi (Carniolan Johns), were stationed at the time. According to Smrekar, they stored him in the barracks like a great treasure, a hundred eyes watching out for anything that might happen to him. Since he was found to be unfit for military service, he was transferred the following day to a sanatorium in Scheifling, not far from Judenburg. Medical examinations found him to be anaemic and of a generally weak constitutionand he was referred to the mental illness observation unit at Garrison Hospital No. 7 in Graz for further examination on account of his nerves. The examinations and interrogations were a torture to him and lasted a full five weeks. They evidently had a lasting effect on him, as can be seen from surviving correspondence, and until the end of his life he would often add the number of the hospital, No. 7, to his signature on drawings.

On 15 April 1916 he was finally discharged as entirely unfit for military service and issued with a certificate to that effect by the replacement battalion command of the Imperial-Royal 17th Infantry Regiment.

Smrekar’s autobiography Henrik Smrekar ‒ črnovojnik presents the First World War in an entirely new light and may thus be compared to the novel The Good Soldier Švejk by the Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek, which has taken its place in the history of world literature.

Jaroslav Hašek (1883–1923), a well-known bohemian, was born the same year as Smrekar and possessed a similarly perceptive, shrewd and witty mind. Both men filled the pages of police reports in their lifetime because of drunkenness, breaches of the peace and affronts to the police and authorities. In both cases, their humour was born out of a hard life. Both stood up to authority and showed the absurdity, futility and madness of war. Rather than covering events on the frontline, they commented on the uncertainty, the senseless denunciations, the interrogations and appearances before various boards and panels, the efforts to establish an individual’s physical and mental fitness for military service. Both Smrekar and Švejk are accused of malingering and, on another occasion, proclaimed to be imbeciles. The authorities never know quite what to do with them. Whereas Švejk reveals the absurdity of the situation by following orders with hair-splitting precision, Smrekar is far less obedient and bombards everyone around him, including his doctors, with humorous drawings. As he notes in his autobiography, he illustrated his own medical report, or the report on his military and “political” career, with sketches and submitted the sketches to his doctors as an appendix to the document, on the grounds that he was the person best informed about himself. This apparently caused the corporal in the hospital office to exclaim: “Thanks to this man, the doctors have been unable to work all morning! Something like this wouldn’t occur to a normal man!”

Every authority knows that nothing destroys its power more thoroughly than laughter. And a caricaturist with the power of suggestion has the ability to direct this order-subverting force against a precise target.

Smrekar overcame the tragedy of the Great War with humour, yet even so he ended Črnovojnik with a moving thought that forcefully condemns the mass sacrifice and senseless deaths. Although the work is a personal testimony, it is written in the third person singular:

“Unconfined, he thought about the tragic carnival of the World War. He compared human beings and animals. The wolf kills when it is hungry, but human beings stage the wildest mutual butcheries, while proclaiming ludicrously lofty slogans, because they are overfed. . . . What is truth? What is up, what is down? Is up down, or is down up? . . . Is culture merely the fruit of ‘higher degenerates’, of the mentally ill? (C. Lombroso!) . . . Is the ’sun’ the sun, or merely deceptive stage lighting? . . . Is Christ the agent of Satan or is Satan the agent of Christ? . . . Is not ‘moral insanity’ a sign of perfect health, are not the ethically incurably infected, in fact, defective? . . . Is the duel between Ormuzd and Ahriman eternal? . . . Is entertaining tragicomedy an end and a goal unto itself? . . . Should the compromise between Satan and Christ prevail?”

Connoisseurs of comic strips and their history agree that Smrekar’s Črnovojnik can be characterised as a proto-comic strip and that it is more than the usual illustrated story or picture book. For Slovenes, it also represents an important insight into one of the supreme workshops of the critical spirit in the country’s cultural history.

In places, Smrekar puts the text in speech bubbles. Everything is written out in his own hand, as is the practice today among the world’s leading exponents of the autobiographical comic strip: “And so we can say without hesitation that you are holding a version of one of the first long-form personal, autobiographical proto-comic strips. If not indeed the very first. On the planet.”(Valetnič 2021, p. 71)

Select bibliography:

Manuscript and transcription of Hinko Smrekar’s complaint in typescript in German, translated by Abis, d. o. o. (NUK, Manuscript Collection, Legacy of Fran Vesel, Hinko Smrekar, Ms 1761)

Hinko Smrekar, Henrik Smrekar − črnovojnik, Ljubljana 1919.

Jaroslav Hašek, Prigode dobrega vojaka Švejka v svetovni vojni, Murska Sobota 1982.

Boris A. Novak, Temni smeh na karnevalu krvavečega mesa, in: Henrik Smrekar, Črnovojnik, Ljubljana 1993.

Zdenko Vrdlovec, Svoboda »presežne pokornosti«,

accesible at: https://www.dnevnik.si/1042684608/magazin/aktualno/svoboda-presezne-pokornosti.

Hinko Smrekar: Črnovojnik in protostripi na Slovenskem (ed. Damir Globočnik, Žiga Valetič), Šmarje – Sap, Brezovica pri Ljubljani 2021.

Author: dr. Alenka Simončič, 2022