Between 1924 and 1933 Smrekar wrote several polemical texts revealing his thoughts and views, which then found realisation in drawings. It is above all in his views of the broader social and political situation that we can find the basis for his cycle.

Mirror of the World

Smrekar's Apocalyptic Vision

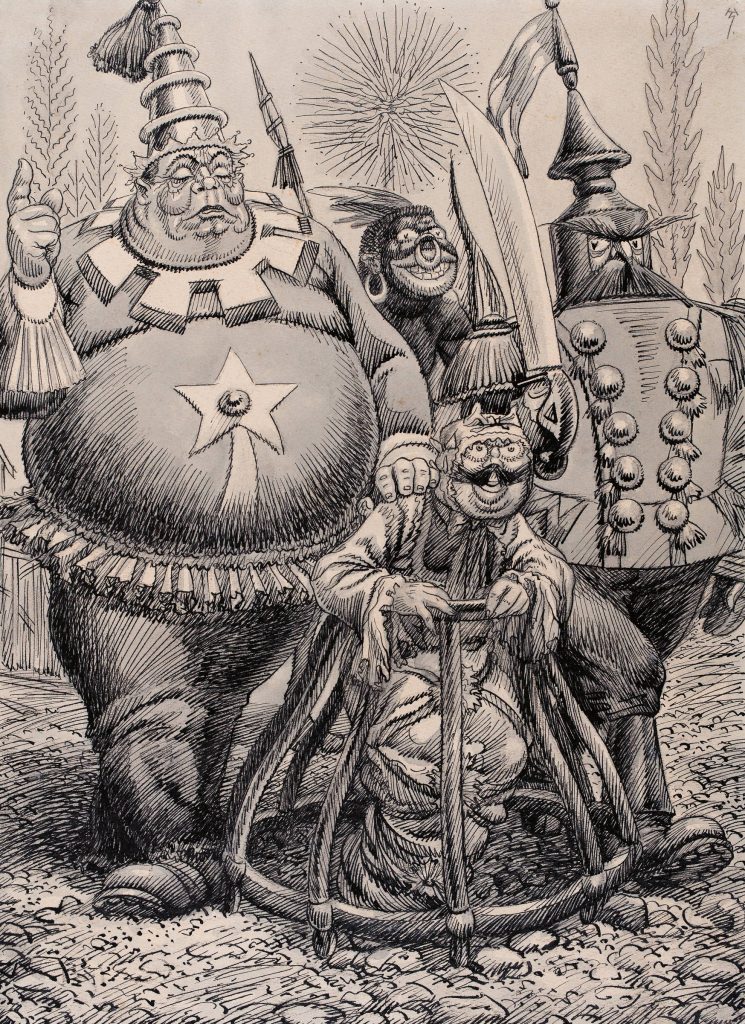

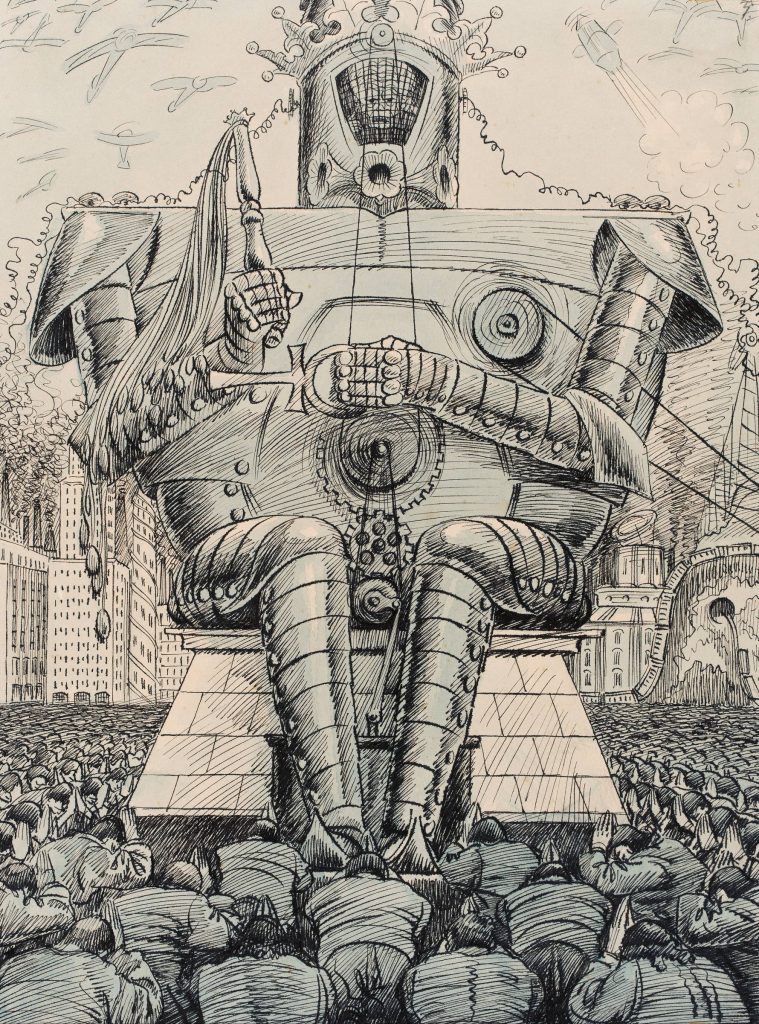

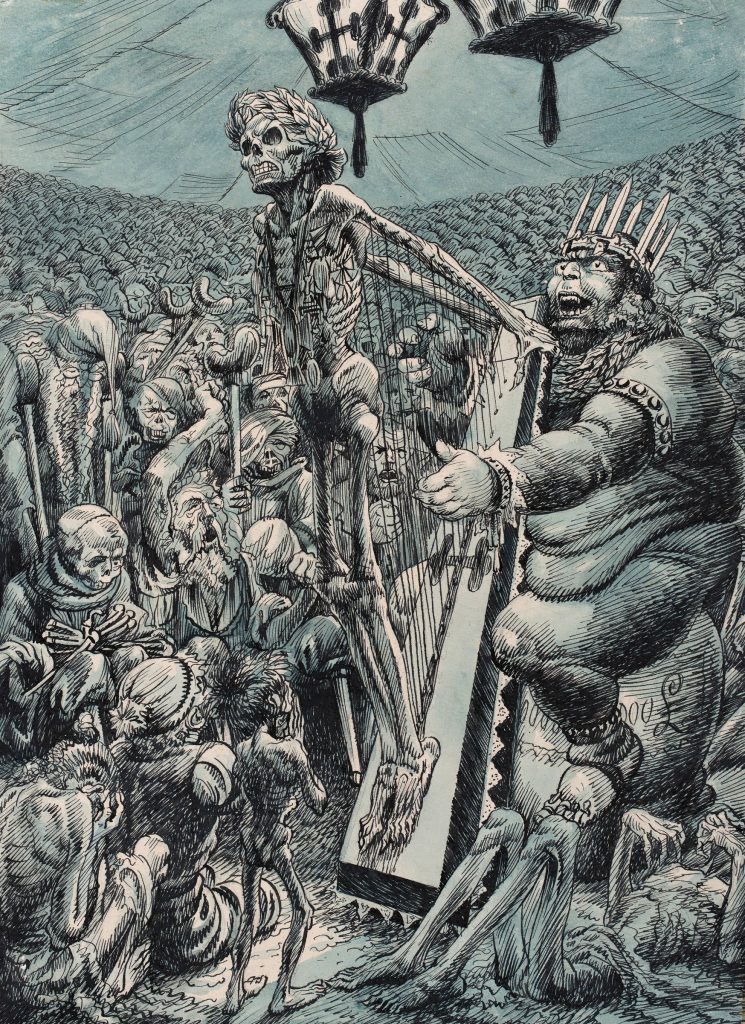

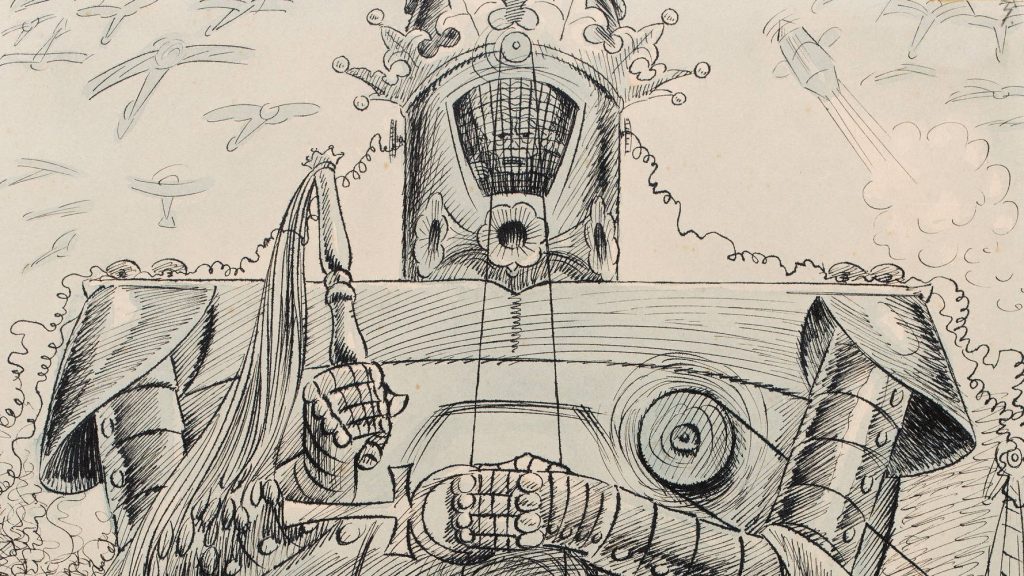

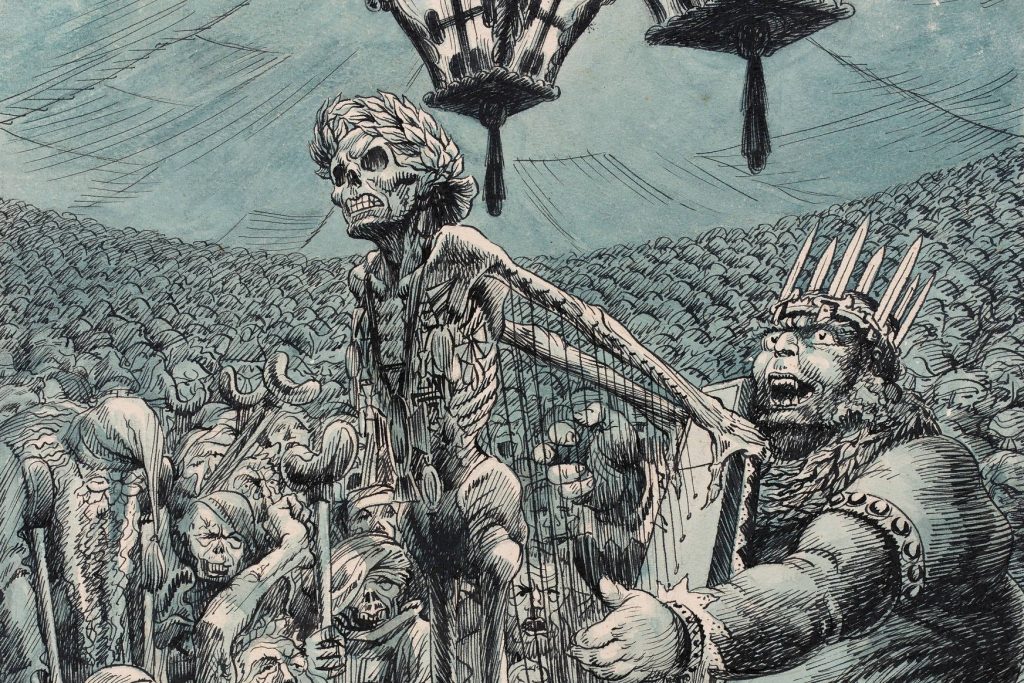

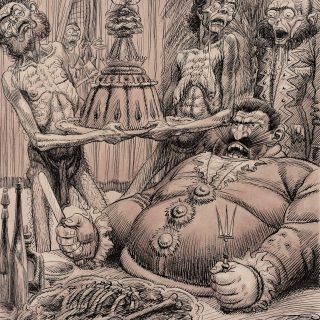

The world will never, ever be ‘saved’ because it will be ruled until its end by three beastly sisters: Stupidity, Malice, Envy. The ruler of the world will be whoever manages to harness them to his triumphal chariot.

Hinko Smrekar

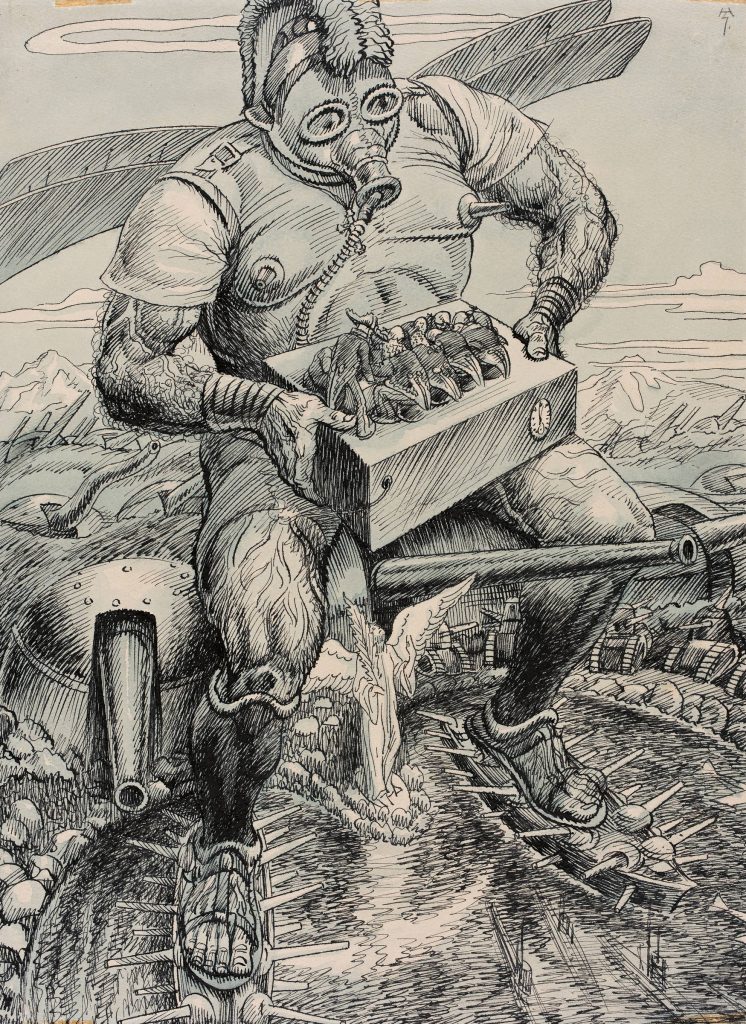

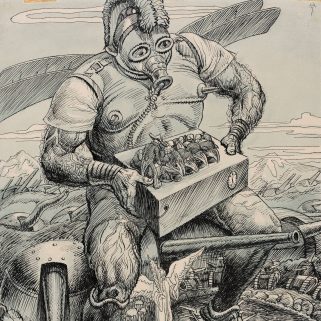

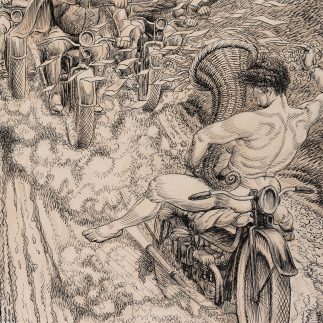

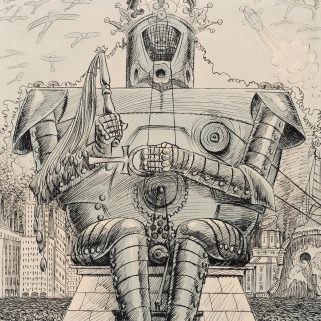

a time of general corruption, rampant charlatanism, confused theories, sensational programmes, the natural germ of deadly rationalism, a time of the spirit of the destructive dictatorship of the machine and the mechanical

Hinko Smrekar on the period between both wars

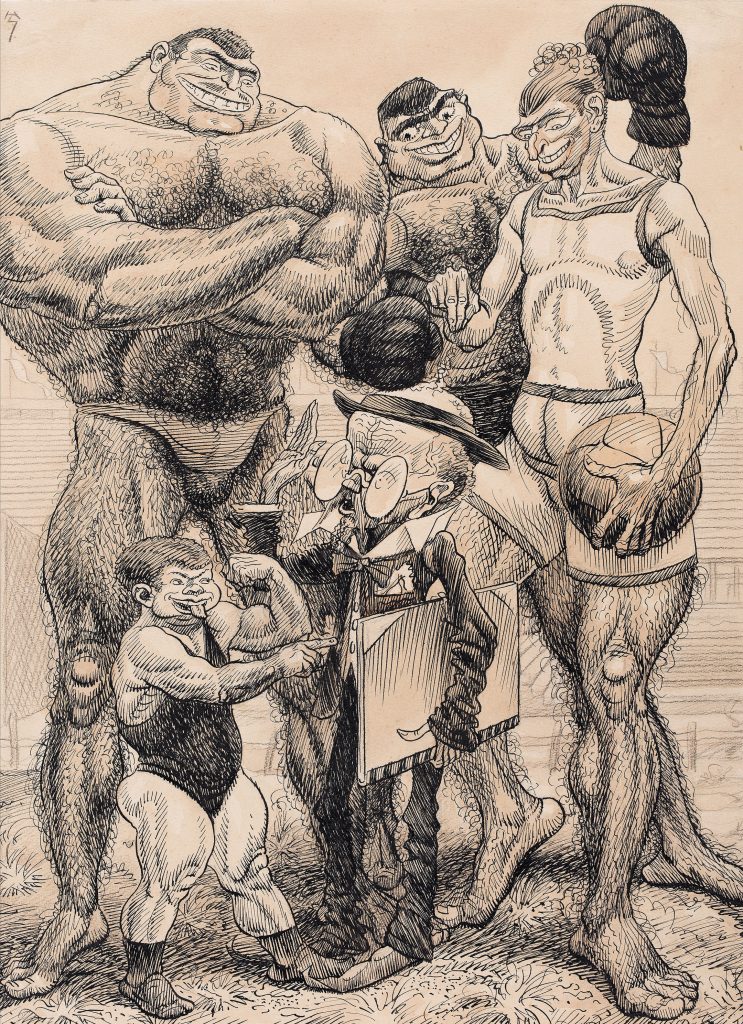

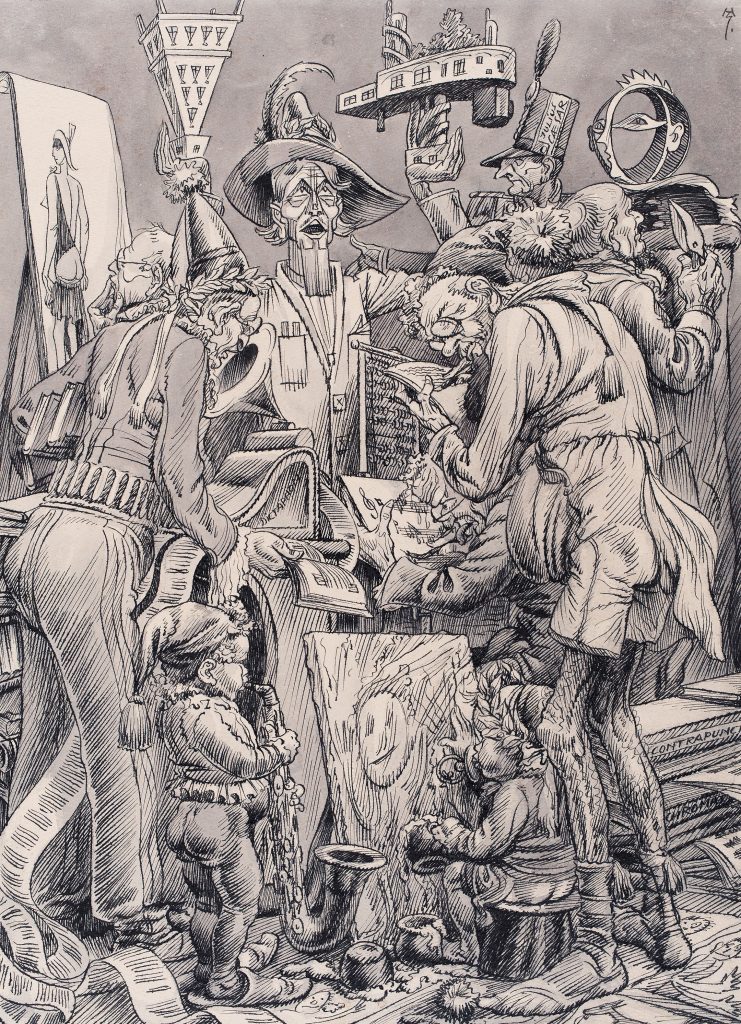

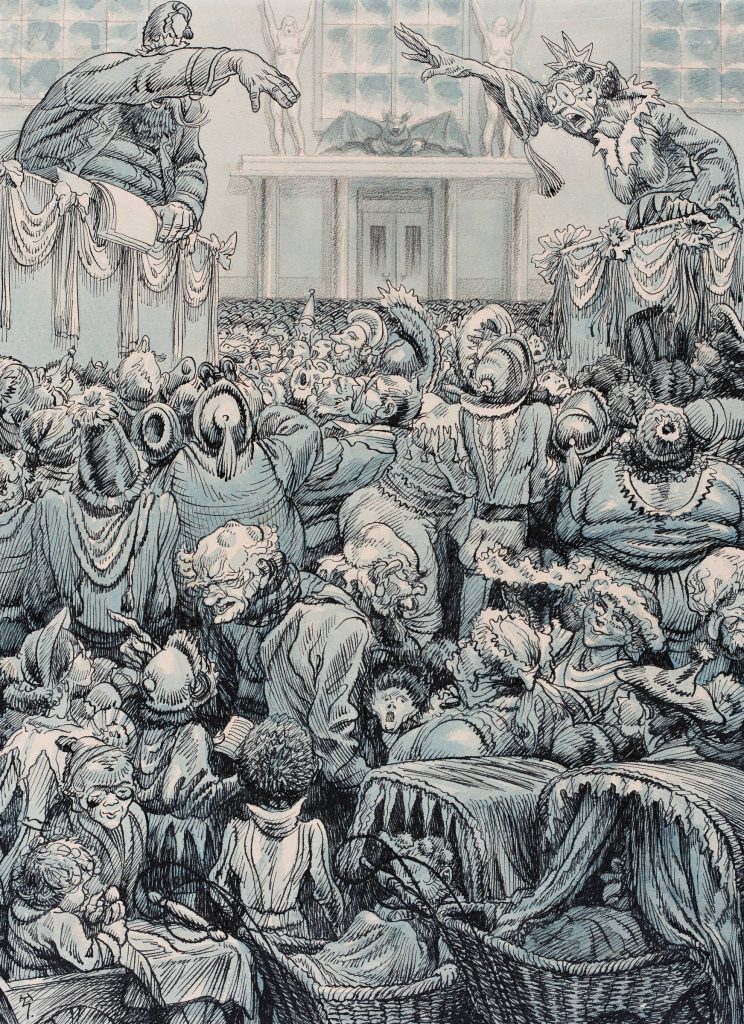

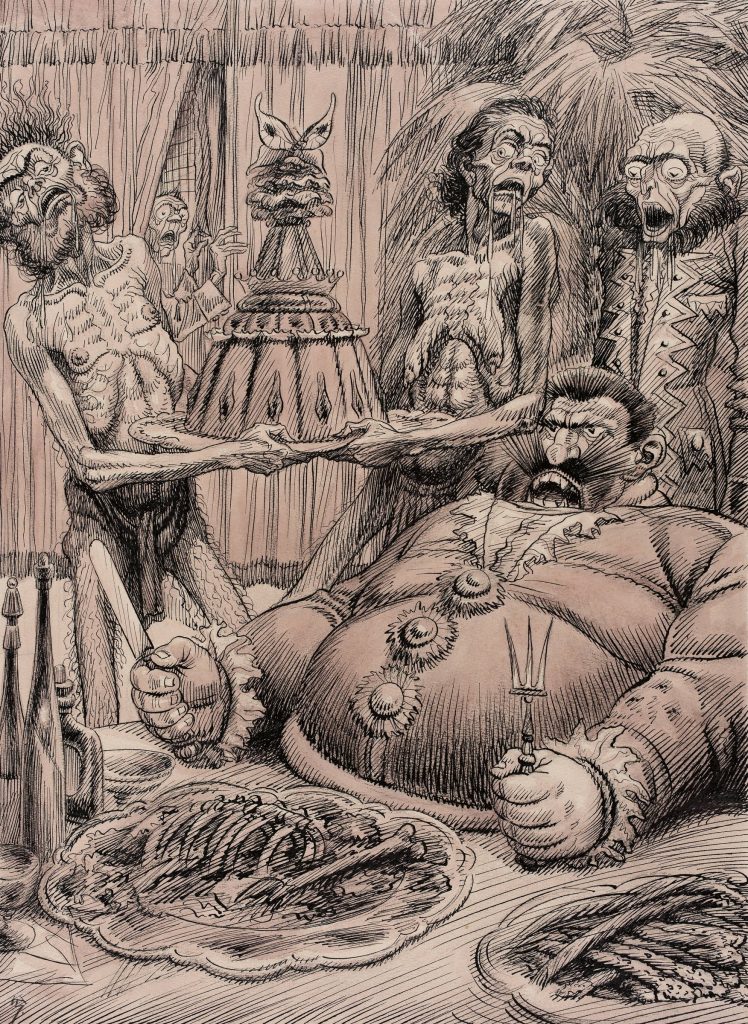

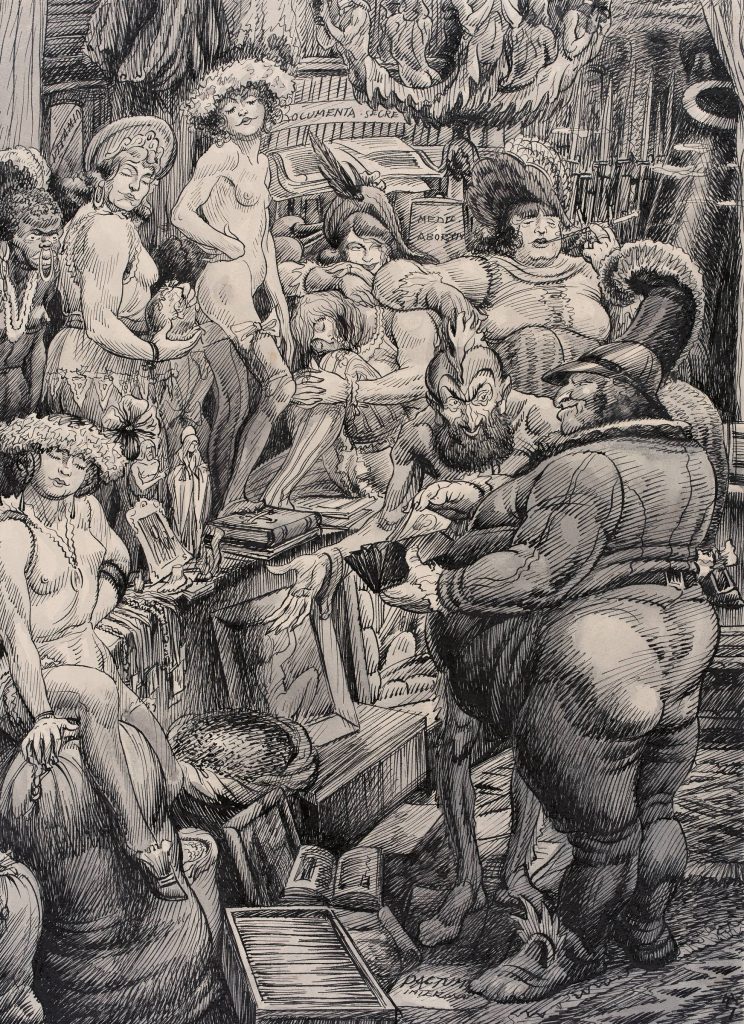

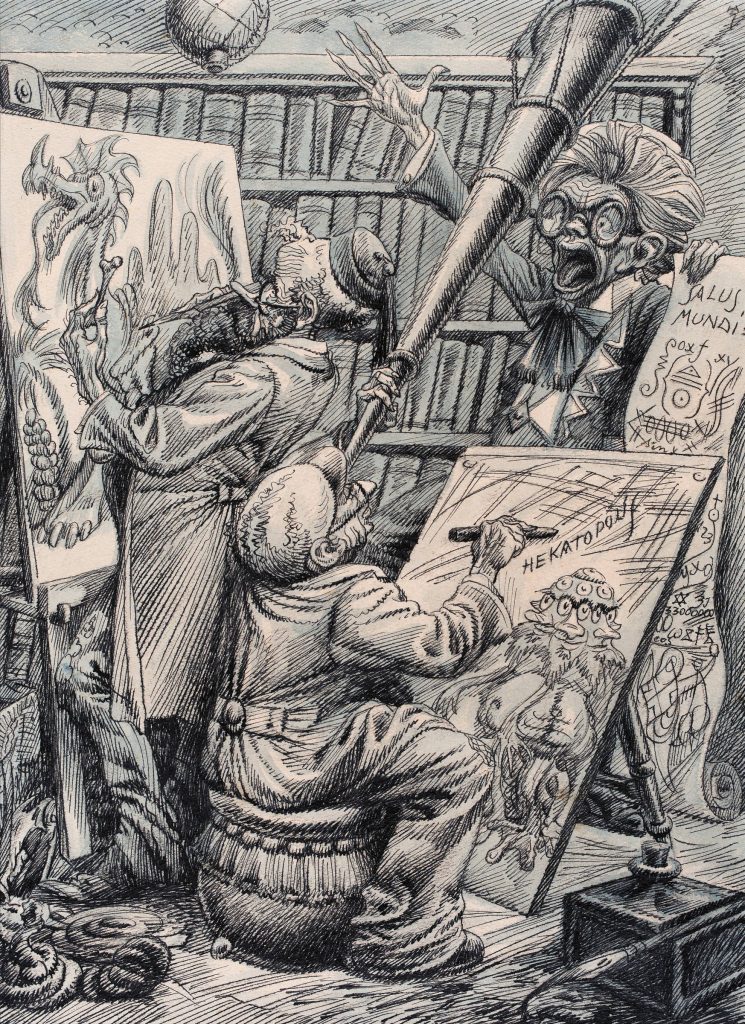

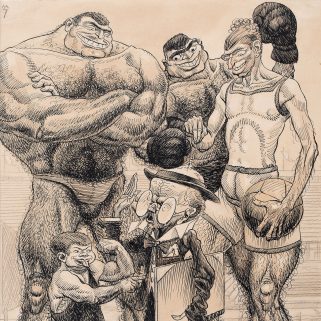

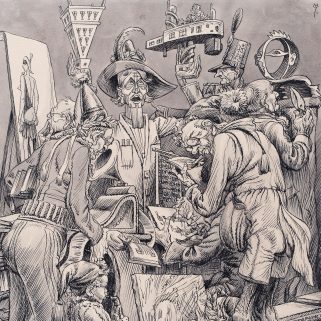

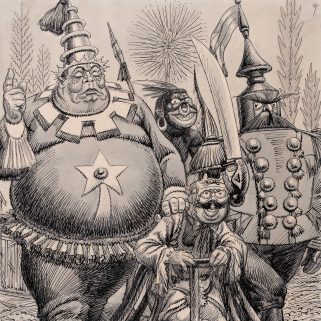

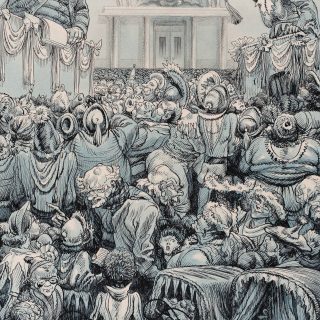

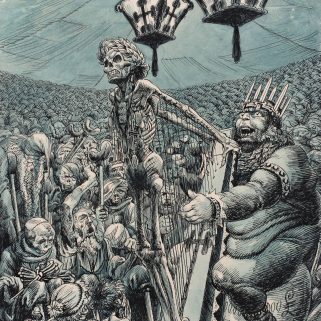

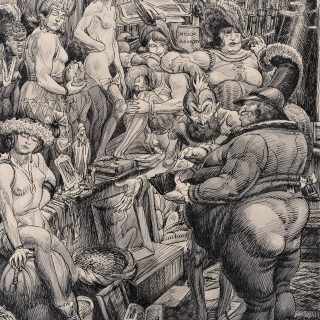

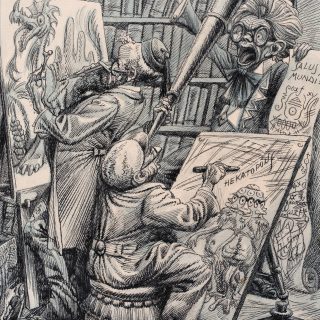

Ever since the mid-nineteenth century the majority of Slovene artists had depicted wonderful worlds, remaining on the surface of past and present and distancing themselves from reality. Smrekar, on the other hand, remained alone in worlds the like of which no Slovene artist before him had ever painted. Those artists who had trained in Zagreb in that period remained close to objective perception even in their socially critical works. In Smrekar’s case, however, everything he saw and felt, everything that moved and shocked him, was given form, and is often barely comprehensible. Only the contemporary Expressionists, among them his friend Fran Tratnik, distorted scenes to such an extent. Smrekar filled every last corner of his pictures with figures in shocking poses and guises, engaged in unusual acts, so that the people of the present might comprehend society’s ills through the errors of the past. He was predicting inevitable events and consequences, given that the year the cycle was created was marked by fateful political events – the victory of Nazism and its assumption of power in Germany, the growth of the Fascist menace and the alarm that was felt around the world. Smrekar had long been thinking about producing a cycle of drawings, for which he had already chosen the title Mirror of the World, in which he would call to account the forces of corruption, hypocrisy and exploitation and all forms of violence and inhumanity.

In just three weeks, he completed the first thirteen drawings. He worked feverishly, saying that his head was buzzing with ideas and he needed an extra pair of hands. He wanted to “get everything out” and the first thirteen sheets were joined by seven new ones. Within a few months the number had reached forty, after which he put everything together in a portfolio. The drawings were in large formats, done in ink and coloured with watercolour in various shades. He wanted the entire portfolio to be printed and put on sale, not just in Slovenia but also abroad. After initial successful discussions with publishers in Vienna and Prague, the negotiations were interrupted by the uncertain situation caused by the approaching Second World War. Justin mentions that a publisher in Slovenia offered to buy the entire cycle for 500 dinars per drawing, but that Smrekar was asking for 1000 dinars for them. In 1933, in an effort to find a buyer, he presented the cycle to the public for the first time in an exhibition at Jakopič’s Art Pavilion in Ljubljana under the slogan: “For sale – all or nothing!” Some of the drawings were printed on postcards, after which Smrekar despaired of the idea.

Newspapers reacted enthusiastically to the exhibition at the Art Pavilion, since it had been a long time since Smrekar had presented new works to the public, and in such numbers. “The sensation of the exhibition is the cycle Mirror of the World,” wrote one newspaper. “Even more powerful, more combative, wittier and more sarcastic”, wrote another. “A unique document of the age that belongs in a public collection”, and so on. In 1936 the government of the Drava Banovina bought 14 of the drawings and presented them to the National Gallery. A drawing entitled Justice was apparently bought by the law courts in Ljubljana, and Smrekar gave the remaining drawings away.

When the art historian Stane Mikuž was attempting to penetrate Smrekar’s artistic essence, he wrote, among other things, that his mentality was like “a veritable witch’s cauldron”. He likened him to the Belgian artist Félicien Rops, who once said to a friend: “Sometimes it seems to me that I am a mythological creature that has been impregnated by the devil; a thousand misshapen creatures live their evil lives inside me and somehow, with goodness or with force, I must expel this thing from myself.”

Critics often accused Smrekar of being tasteless, even pornographic, in his works, yet in the case of the exhibition in 1933 they were unanimous that the works from the cycle belonged in a public collection, despite the fact that the true message was lost in the over-complex and overfull compositions, rendering them incomprehensible.

Smrekar borrowed from Egyptian and other ancient iconography in the cycle and the manner in which he filled the space and interwove the figures in the drawings are reminiscent of the scenes of hell, fallen angels or dances of death from paintings in past centuries. His rich drawing and fertile imagination link him to artists such as Gustave Doré or the Czech painter Maximilian Pirner (1854–1924), while the apocalyptic visions and invisible terrors connect him to Alfred Kubin. In terms of content, parallels can be sought with artists who tackled more convincing but also tragic topics, such as the Spanish painter Francisco Goya in his cycle of prints entitled The Follies (1816–1824) and, in particular, in The Horrors of War (1810–1814), where he declared his aversion to political violence and all his loathing and disgust at such actions, when all thoughts of reason, freedom and humanity were forgotten; or with the realistic battlefield scenes by the Russian painter Vasily Vereshchagin (1842–1904), who believed it to be necessary to paint the horror, fear and disastrous consequences of fighting in order to deter humanity from bloody wars.