Hinko Smrekar’s cycle Mirror of the World, a collection of 31 intricate drawings, can be understood as the endpoint of the artist’s societal predictions, his desperation, turbulent mental health and relentless commentary on the darkest aspects of human nature, which were corroborated by near-daily political earthquakes in 1932 and 1933. The world of drawings, which are shockingly critical of everyone and everything, is void of redemption, hope and mercy, and ruled by acid cynicism, decadent indifference and genocidal violence. The cycle offers a panoramic insight into the dysfunction of modern European society from the perspective of politics, poverty, social excesses, science, art and the looming war.

The Breakdown of Civilisation

Hinko Smrekar: Mirror of the World cycle, 1932–1933

The centre cannot hold – Politics

At its core, Smrekar’s perspective was Slovenian, anti-capitalist and anti-fascist.

After the First World War and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, around a third of the Slovenian ethnic territory was delegated to Italy and Austria, two Catholic and soon to be fascist countries. For the first time in a thousand years, the majority of Slovenians stepped away from “German” rule and joined the emerging Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, with Belgrade as its capital. At the time the drawings were done, Ljubljana was the centre of the Drava Banovina, a province of the reorganised Kingdom of Yugoslavia, where the king took over all levers of power after the ratification of the new constitution in 1929. Slovenian direct experience with fascism across the border encouraged its patriotism and, together with domestic dictatorship, offered an unvarnished glimpse into totalitarian systems. Italian crimes are especially bitter for Slovenians, since most of the world has forgotten just how much Italy was involved in the spread of fascism before the Second World War. On 13 July 1920 an Italian fascist mob burned down the Slovenian National Hall in Trieste and after Mussolini’s march on Rome in October 1922, the Fascists took control of the Kingdom of Italy. On the eastern coast of the Adriatic under Italian control, the Fascists banned the use of the Slovenian and Croatian languages, disturbed Slovenian businesses and institutions (the ones the hooligans had not already destroyed before 1922), closed Slovenian schools, Italianised Slovenian last names and deported many Slovenians to the south of Italy.

Today, racism is more thought of as a system of oppression against people from other continents who are different from us (whoever “us” is) in skin pigmentation or some shallow physical, psychological and cultural specifics. Institutional racism in Europe of the 20th century mostly targeted other European nations, whose similarity to the supposed masters presented a far greater danger than distant peoples – like the Jews, the Slavs could infiltrate and corrupt your society. Slovenians, as Slavs, were considered inferior by the Fascists and Untermenschen by the Nazis. The Italian and German (and English) words for slaves (sciavi, Sklaven) are relics of the time around 10th century AD, when the Swedish Vikings were capturing Slavs along the banks of Dnieper River and selling them as slaves to the Byzantines and the Arabs. Both Fascists and Nazis would spare the acceptable racial fragments that could be assimilated, while the rest would, in time, share the fate of other peoples, especially the Jews.

Gangster methods, later used by Hitler, and the abuse of anti-Bolshevism to achieve his own dictatorial ambitions were honed by Il Duce, who dreamt of restoring the Roman Empire and in due course carved out territory along the eastern Adriatic coast, home to many Italians, or rather the descendants of the Venetian Republic. In 1929, Mussolini’s Italy and the Vatican signed the Lateran Treaty, thus settling the fate of the Papal State, and prepared the ground for other compromises between the Roman Catholic Church and totalitarian, but God-fearing countries.

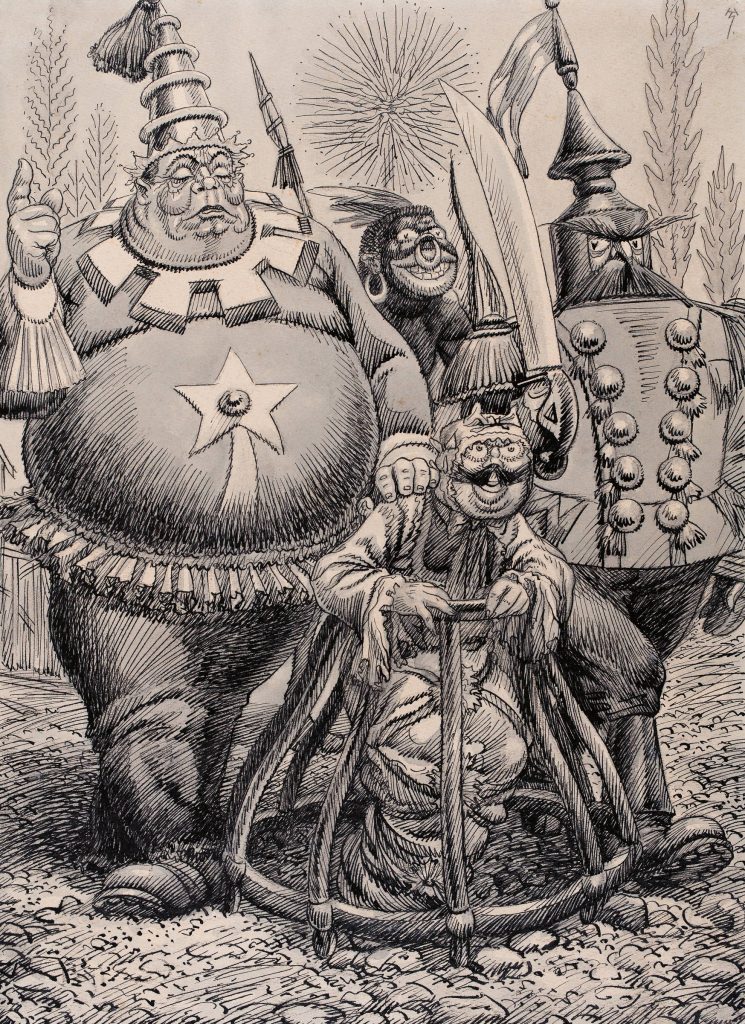

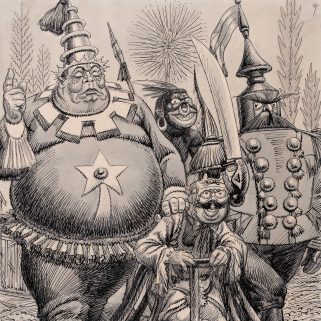

The main enemy of the right was the (mostly Slavic) Soviet Union, officially an atheist revolutionary state that strove to export its anti-capitalist ideology across the world. The clash of capital and communism is the theme of Smrekar’s first drawing in the cycle (Dumping), where a ghastly centipede holding sickles and hammers in its innumerable hands is attacking the greedy mogul buried underneath his riches. In the drawing Capital and the Soviets (Fighting over the Proletarian) we see the fight between a representative of cynical communism, with a five-pointed star on his uniform and a hammer-sickle in his hand and a soldier with a modified helmet of the Roman centurion, who has his behind kissed by a man in a hat reminiscent of the papal tiara. The figure of Capital (a fat sinister man wearing the sign of the British pound – the preeminent international currency of its time) has been in Smrekar’s repertoire for decades and the artist blamed most of the world’s woes on Man’s lust for profit.

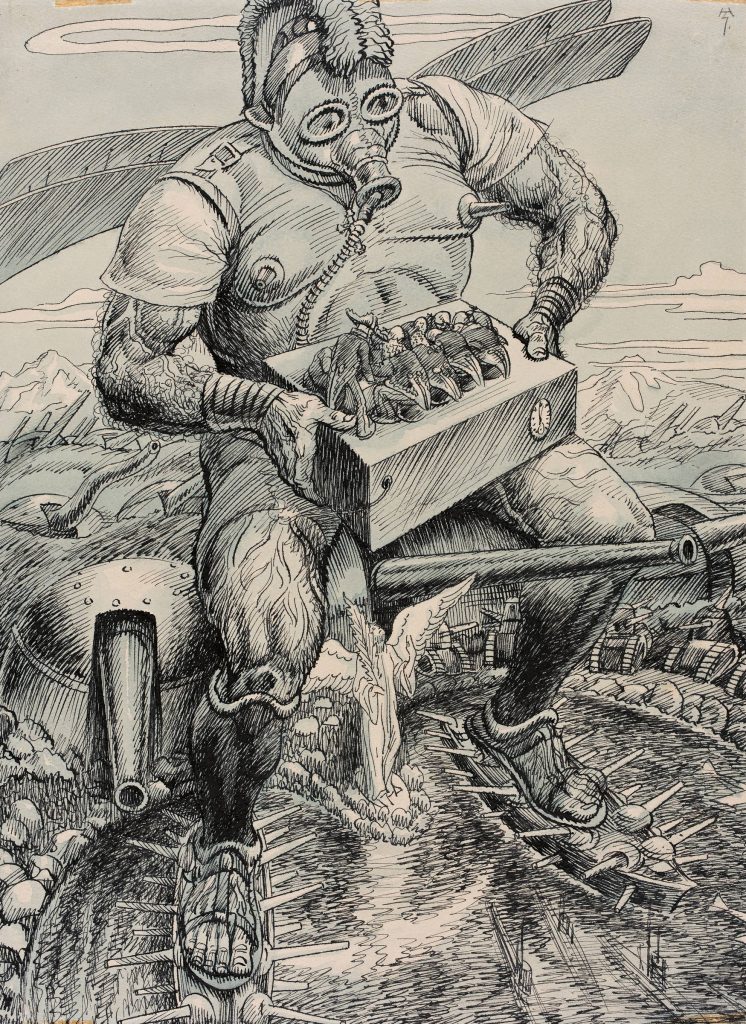

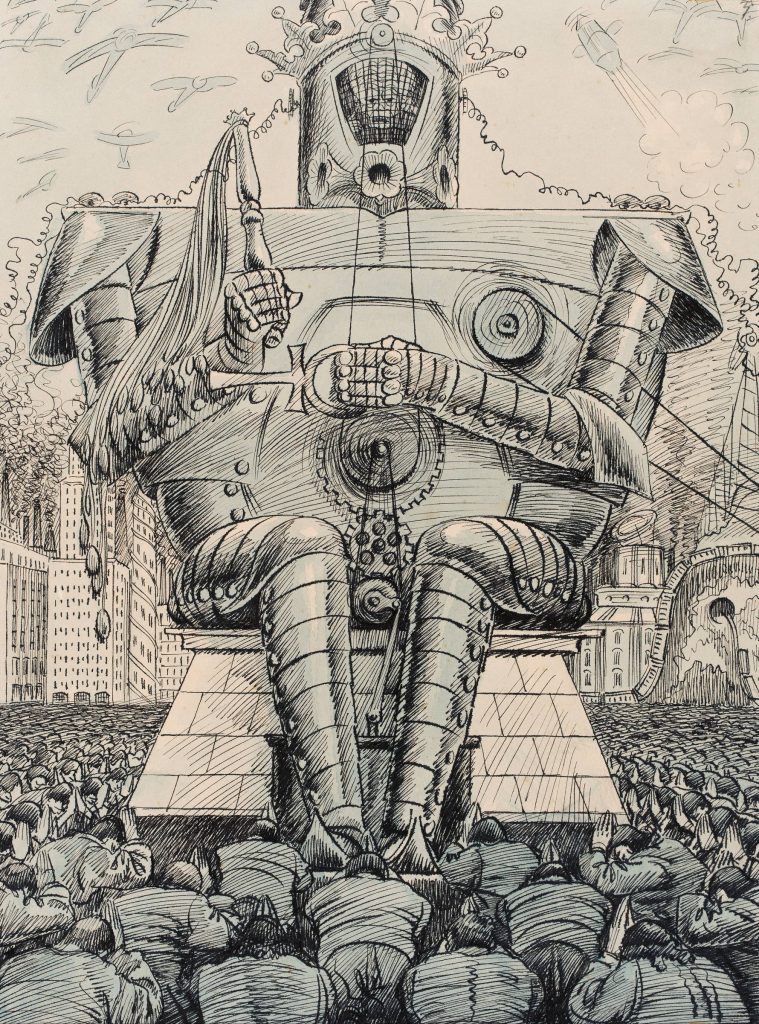

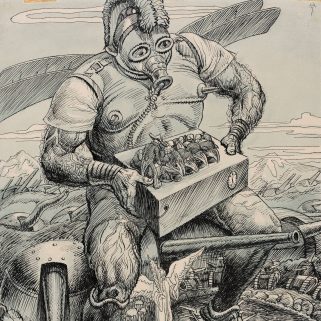

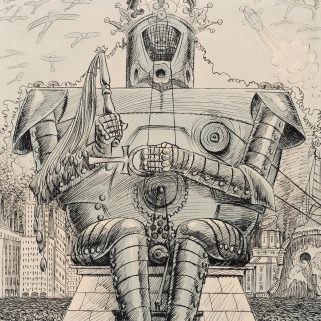

God of Our Age builds on this thesis; the gigantic pharaoh-robot (a derivation of a Central-European word for a serf) is controlled by some sort of demonic alien and worshiped by the citizens of a futuristic metropolis. Smrekar paid attention to film production (he drew himself as Charlie Chaplin and also depicted Marlene Dietrich) and the drawing is reminiscent of the scenes from the movie Metropolis, which premiered in 1927. The Fascists worshipped speed, technology and weapons – they saw it as a way to regain threatened manhood – and the Angel of Peace presents the god of war, surrounded by tanks and with a gas mask on his face, waiting for the diplomats behind the table to trigger the bomb.

The great game and the perversion of (international) law are addressed by Justice, whose eyes are not covered and who has, despite the Christian imagery surrounding her, taken the side of the powerful and in the name of money crushed the weak. Two men drink from her hefty breasts; one in an eastern fez hat and another in that of a western admiral – a reminder of the realpolitik games in the Mediterranean.

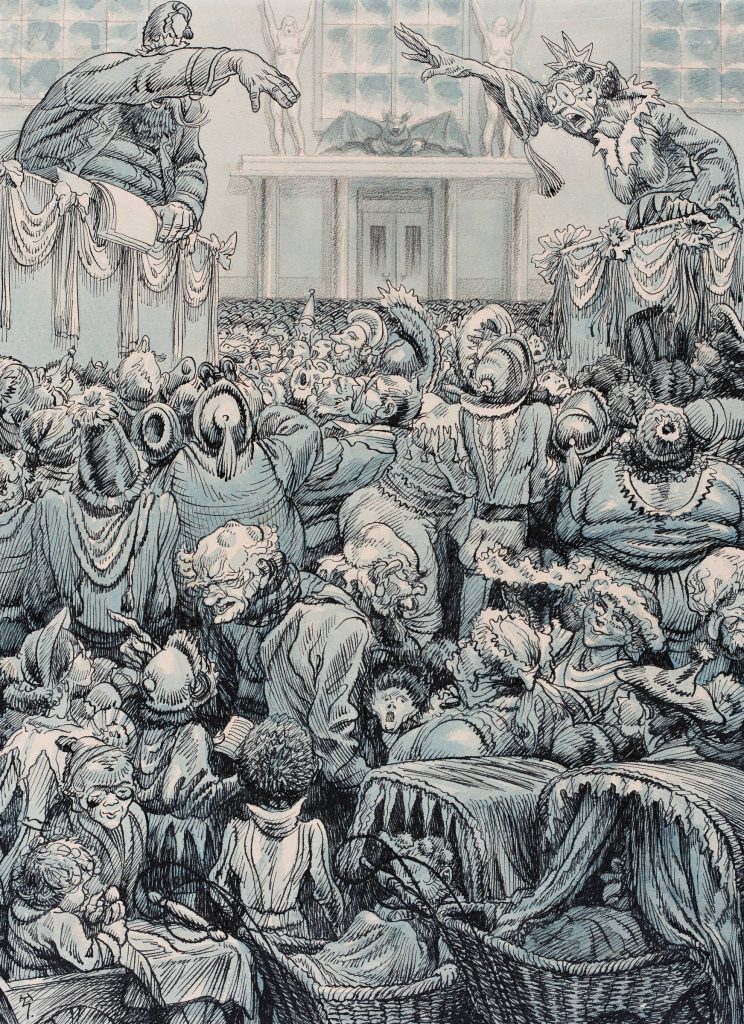

Commentary on the total polarisation of society is evident in the drawing Politics Above All, where the populace is enthralled by two speakers with their right hand extended before them. Both are dressed as the harbingers of freedom: the woman is the Roman Libertas, the man the proponent of manumission in a Phrygian hat. The era between 1919 and 1941 was a time when charismatic leaders used their hypnotic speeches to channel the yearnings of the common people for stability, security, dignity and prosperity and proposed ethnic, moral and parliamentary cleansing as a tool to achieve this. It began with the Italian poet and proto-fascist thinker Gabriele D’Annunzio (1963–1938), who at the end of the First World War and just a few kilometres from Slovenian lands established a short-lived totalitarian-corporatist city state in the port city of Rijeka (Italian Fiume), on the Croatian coast.

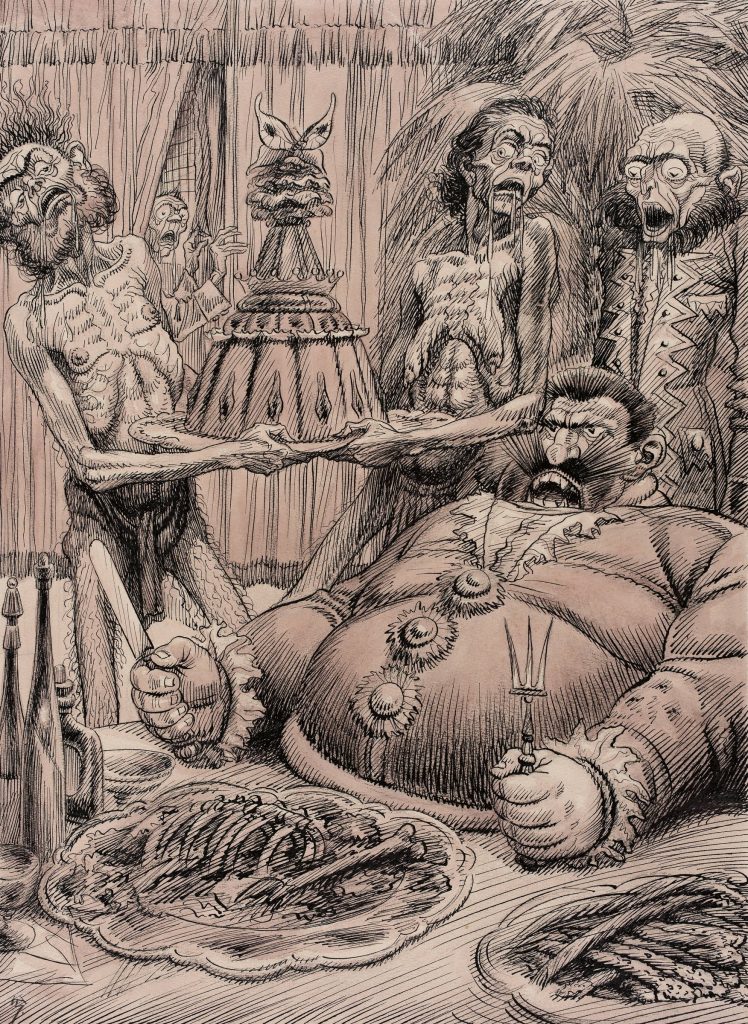

Things fall apart – Social Welfare

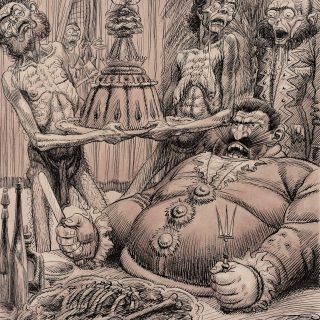

Yugoslavia, like the rest of the world in the 1930s, found itself in an economic crisis. The Unemployed gathered in front of an office that threw them half a loaf, with alms provided by a sinister Jewish wizard. In the drawing Public Charity, a corpulent ruler is feeding a chained emaciated subject a spoonful of healing syrup. In Grooming a Subject, a ruler–court jester in a tiara and a soldier with a caricatured Prussian helmet, the Pickelhaube, are teaching their underling to walk, while in Social Welfare a ruler demands a feast for himself while his servants starve.

The state social services, or lack thereof, were an important factor in the radicalisation of masses. When the Drava Banovina was cutting its patronage of contemporary artists, the artists protested; at the same time, the council of the Banovina noted that poverty was kindling revolutionary ideas among the educated youth. This was understood by both the European communists as well as the Fascists and Nazis – when the latter took over, their support of the war industry and grand public projects helped reduce the terrible unemployment that was crushing the working and middle classes. On several occasions, Smrekar depicted the fight for the proletariat as a duel between communism and capitalism that are about to tear the hapless worker in half. Like other Slovenian artists, Smrekar often asked the Banovina for financial support and, apparently, in their inadequate response, mostly saw a lever for the government to control the languishing masses – his own histrionic letters to officials mostly resulted in parsimonious help.

The ceremony of innocence is drowned – Society

Smrekar’s wrath was directed at adults who behaved horribly and were rewarded for it with attention, influence and money. His drawings Life – Carnival and Human Zoo show two fairs of vanity; in the first, pathological narcissists gathered, each in their own costume and absorbed in their own word – on the collar of a dandy lower right Smrekar wrote: le monde c’est moi – a reference to the apocryphal statement by the absolutist Sun King Louis XIV. In the other drawing we see genteel anthropomorphic animals strolling about, all wearing respectable clothes. Parallels between human and animal behaviour have been around for millennia, while this scene can be interpreted as the questioning of the hierarchy that uncritically considered humans to be more civilised.

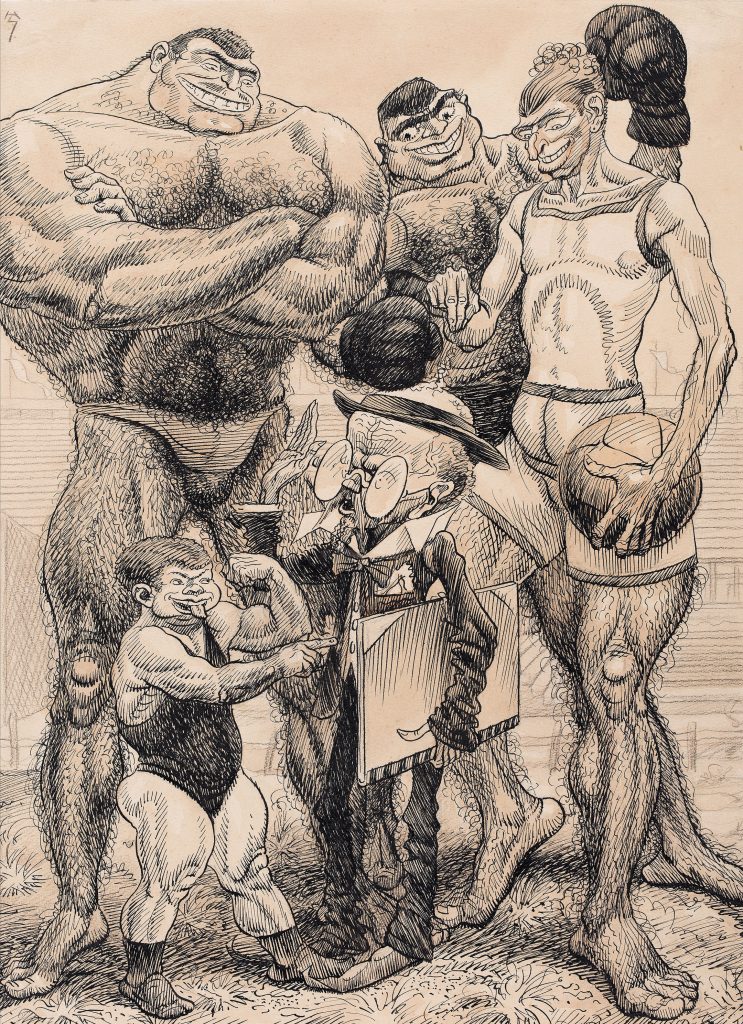

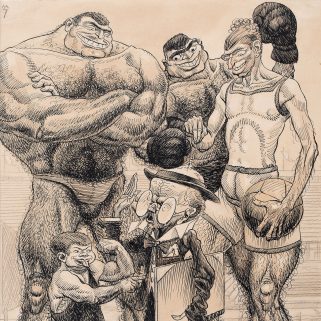

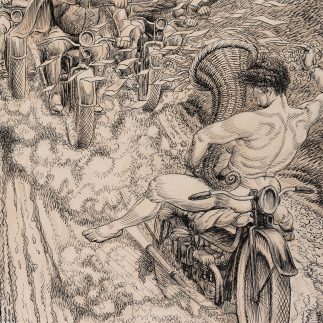

Smrekar believed that the problems stemmed from the crisis of values – for decades, he was sensitive to materialism and the neglect of spiritual culture. In the drawing Fortuna, the ancient personification of welfare, spouting money and coins from her horn of plenty, is chased by a horde of parvenus on motorbikes. Biceps and Brains, on the other hand, comments on the baleful transition from the society of the mind, represented by the rickety artists, to the society of brute force, personified by the menacing athletes. In the 1930s democracy finally lost its crucial element – introducing changes through cultural persuasion. The argument-making was taken over by militias, paramilitary organisations, hooligans – presented as “the voice of ordinary working people”. Like the Fascist blackshirts a decade earlier, the Hitlerite brownshirts spread terror in the early thirties and Slovenian newspapers documented the Nazi militia led by Ernst Röhm and their crimes.

In the years that Slovenians experienced horrible pressure from all sides, Smrekar did not pay much attention to the troubles of other marginalised groups and often depicted them as servants of the great colonisers. American aborigines, Africans and the Jews remained at the edges of his drawings, caricatured as grotesquely as the Europeans and reduced to the widespread racist stereotypes that Smrekar uncritically gleaned from Viennese magazines: submissive Indians, primitive blacks and sinister Jews. Just as he showed no restraint with male politicians, he was coarse towards women who were either corpulent madames of the Church and Capital or svelte degenerate prostitutes (The Supreme Goddess, Morals of Fashion). Today, we see such parallels as unacceptable, of course, but the images reveal three intertwined processes: one was the general attitude towards certain topics, the other is the mental reflex that makes denigrated people bring down their bullies by equating them with even “worse” Others and the last is the fact that the victims of chauvinism have their own chauvinistic prejudices.

Smrekar’s sexual purism developed through the years, maybe as a response to his chronic bachelorhood, unorthodox public behaviour, and intensive friendships with male artists. When he was 21, Smrekar illustrated the sexual escapades of his clique and with the signature “Svinko Sifla” alluded to syphilis. We do not know if Smrekar was actually infected, but an untreated disease in its latent phase would definitely explain at least some of his later physical and mental health problems. In any case, allusions to prostitution, abortion, zoophilia (woman holding a lapdog with a long tongue), cuckolding and same-sex relations were present in his cycle as much as criticism of the Catholic Church and the traditionalists. The sexual practices of the ruling elite have been used as a cudgel by the opposition since the times of the Ancient Greeks and the leader of the Hitlerite bandits Röhm and his circle were also outed as homosexuals by the liberal press.

The drawing that most personifies Smrekar’s cynicism and the indictment of the entire system is TheIdealist and the Realist. The former, with angel wings and a thorny rose instead of a tail, is a halfwit distracted by the blooming tree, while the latter, a hybrid between human and animal wearing rags, is chewing on bones on the ground.

The widening gyre – Technology and Art

In Smrekar’s view, the pitfalls of modern technology and the arts contributed to the state of the world. The most direct link between this argument and fascism was Advertising, a commentary on the astounding propaganda successes of the totalitarian regimes that cemented their power through modern media. On the right, we recognise Benito Mussolini (1883–1945), who as the genius of genii appeared out of the behind of a prostitute. The Italian dictator was born in the same year as Smrekar and a similar drawing (with a domestic collaborator climbing a ladder into the dictator’s rump) proved fatal for the artist during the Italian occupation of Ljubljana during the Second World War.

Morals of Fashion and Miss Sensation (Hollywood) once again equate modern trends with (female) prostitution. Miss, most readily comparable to Advertising, is accompanied by two fantastic creatures, similar to the ones Smrekar drew two decades earlier in Delirium and inspired by Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516), a Renaissance painter who also condemned his society and time.

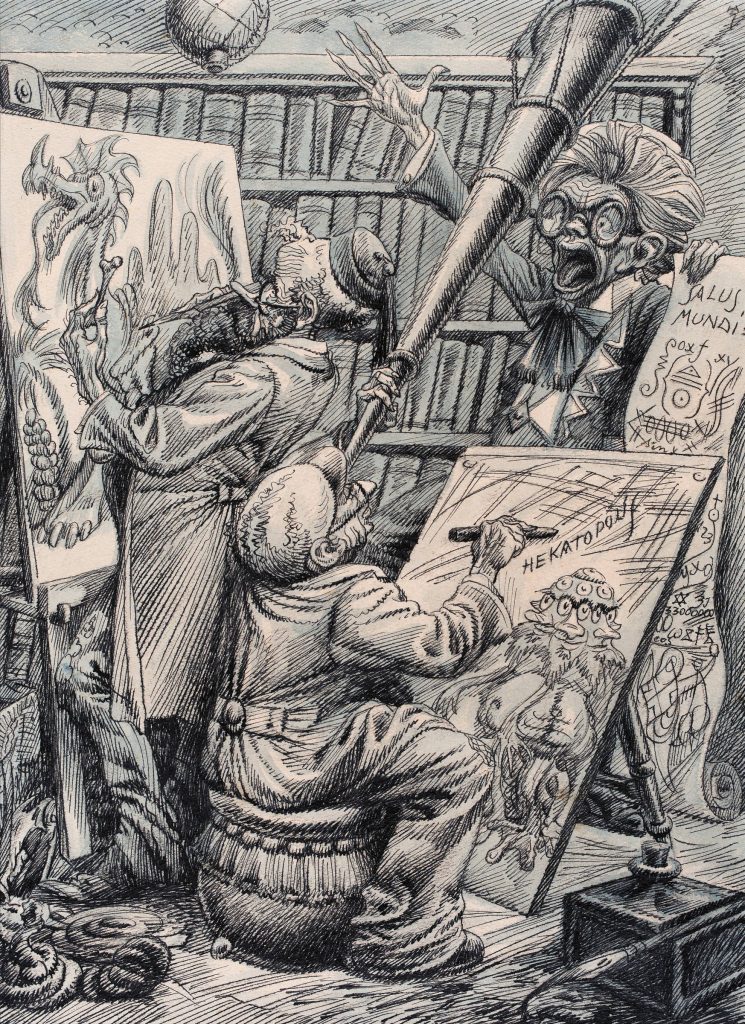

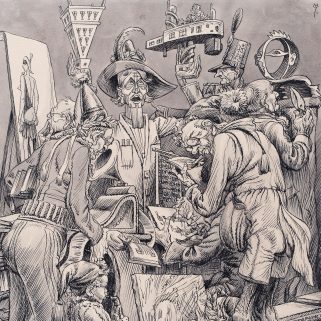

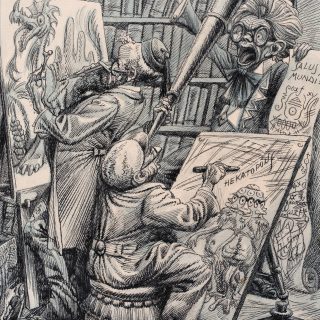

Doctors in a book-filled room (Progress of Medicine) conduct bizarre operations, while the artists (Science and Art) draw dinosaurs and aliens, clearly inspired by contemporary discoveries and hypotheses. Palaeontology grew exponentially since the 19th century, while belief before the First World War that canals on Mars point to civilisation on the red planet, influenced popular culture such as radio plays, novels and comics. The Mystics, the new-age pagan priests, are searching for ways to control the uncontrollable. Some of them look to heaven, others into cards, while their flock bows now to child-king, then to wizard-druid or just to a sack of flour.

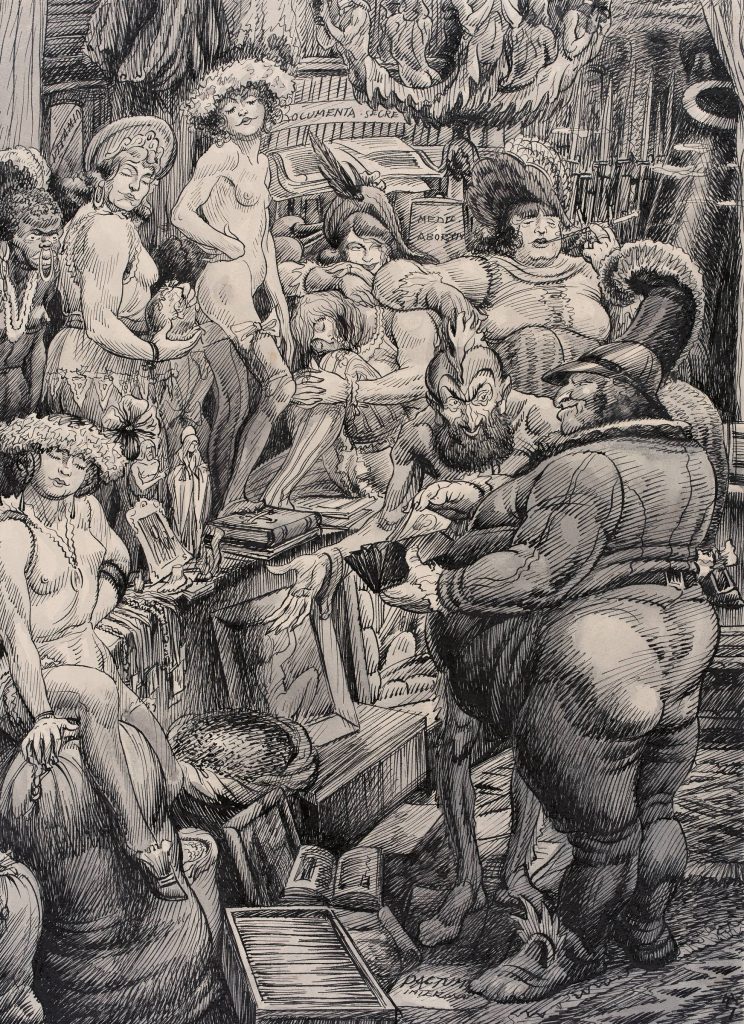

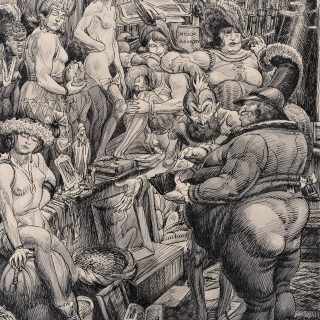

Parvenu and Art and Business address Smrekar’s perennial worry: the rich and the influential have no taste, so they support vulgar art. Prior to the First World War Smrekar, dressed the director of the Ljubljana theatre in coquettish woman’s undergarments and put him on a stage in front of an audience of swine, while here we see the nouveau riche picking an erotic artwork. Smrekar, who himself was often accused of lewdness, was friends with Matej Sternen, a Slovenian Impressionist who is mostly known today for his female nudes and who owned a collection of erotic works, which he also drew himself.

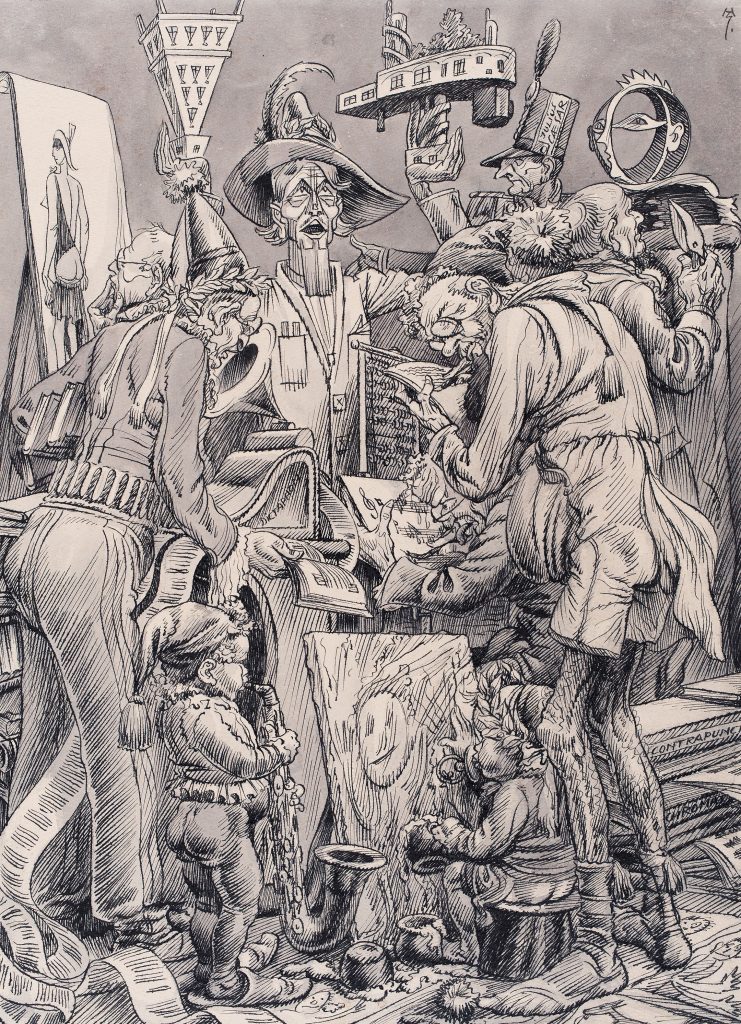

Art Nouveau showcases changes in the visual arts, music and architecture; a Dictaphone enabling hyper-production, jazz saxophone, spontaneous painting created by a baby, and changes of counterpoint in classical music. In the middle we see a representative of Bauhaus, who slightly resembles the Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik, presenting his models, while on the left and the right we see Picasso-like works.

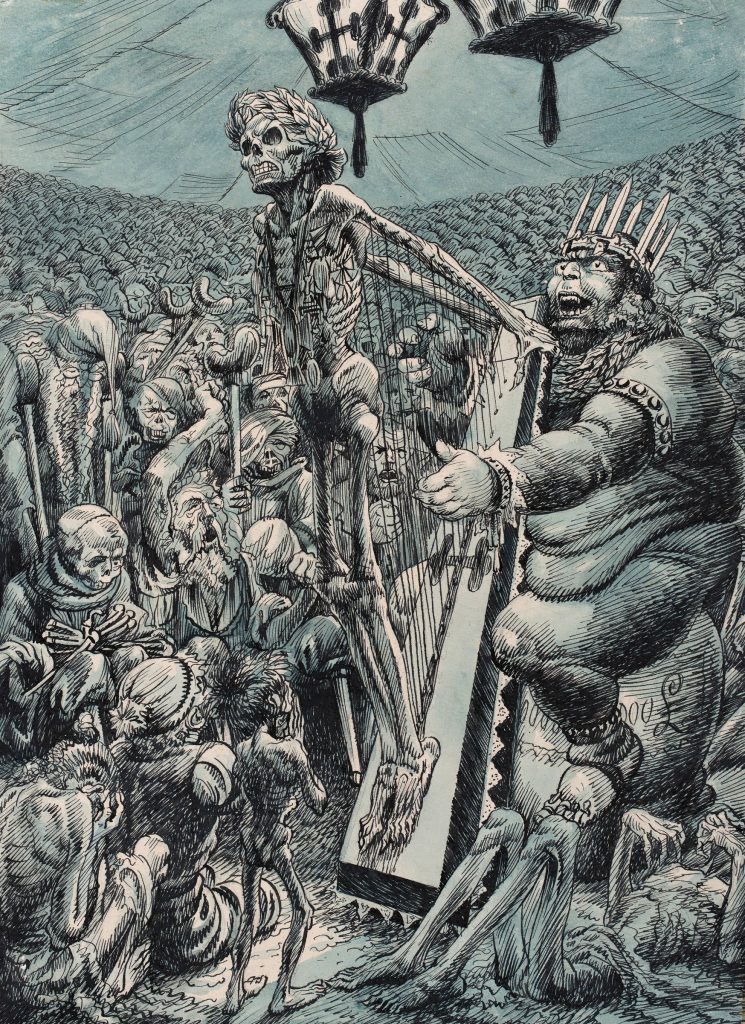

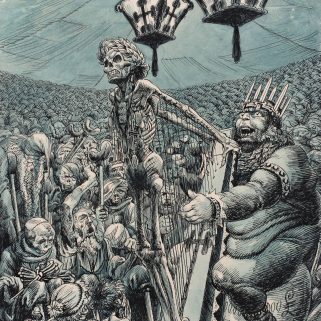

Blood-dimmed tide – The War

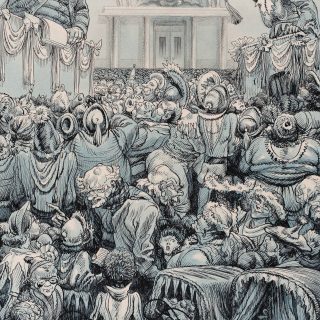

Apocalypse had been looming for quite some time and in Smrekar’s most prophetic drawing, Slag, from 1932, we see a river of corpses flowing out of a death factory on a hill. Dictator’s Avenue shocks us with hung emaciated corpses, inspected by a pleased ruler in a papal tiara that ends in a clenched fist. Hymn of Thanks to the World War is a haunting assembly of the living dead, with a ruler serenading about the beauty of death and violence. The purification that in the eyes of pathological masochists was wrought by war was at hand.

On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler finally became German chancellor with the help of scheming conservative politicians. On 5 March 1933, about a week after the burning of the Reichstag, which was the work of a lone Dutch communist, Germany held more parliamentary elections and the Nazis won a relative majority. On 11 March, the newspapers were already reporting on “the inauguration of Hitler’s Third Reich”. Other political parties were either broken apart, outlawed or imploded on their own. In the middle of July 1933, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party was the only legal party in the country. Like Mussolini a decade earlier, Hitler was fast, ruthless and completely cynical.

On 1 August 1934, Slovenec, a political daily, published a brief at the bottom of its front page that the “President of the Reich” Hindenburg was ill, but stable. That Hindenburg’s health was gravely deteriorating was known for weeks, but the consequence of events was shocking regardless. A day later it was apparent that Hindenburg was dying and on 3 August the newspapers did not report just the President’s death a day earlier but Hitler’s final complete takeover of Germany. The chancellor became the Führer.

The dramatic events surrounding Hindenburg’s death managed to push from the headlines the failed putsch in Austria, where Hitlerites managed to assassinate the Fascist prime minister Engelbert Dollfuss (1892–1934) in Vienna, who had rejected unification with Germany. The rivalry between the Führer and Il Duce misled Western politicians, who constantly appeased Italy. The Little Entente – a defence alliance between Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia – could not encourage Yugoslavia for long. The alliance’s institutional framework was agreed in May 1933, but was irreparably damaged in October 1934, when the Yugoslavian dictator Alexander Karađorđević was assassinated in Marseilles by a Bulgarian extremist, probably with the blessing of Italian and Croatian fascists. The West had no intention to escalate the conflict with Italy (or Germany, for that matter) and together in the following years they trampled on the rights of Eastern Europe in the name of peace. Thus, the totalitarians and their eternal companion, the Capital, were given ample time to prepare.

Anarchy is unleashed upon the world – Conclusion

The Mirror of the World cycle brought Smrekar to breaking point – for the next five years, he devoted himself to youth illustrations and again spent at least some time in a psychiatric hospital. His complete retreat from politics is understandable, since neither hollow political compromises nor public pacifism or international commitments could prevent the war. Shortly before its outbreak, Smrekar took up satire again, but his drawings for Politična izdaja (Political Edition) deal with daily politics. His general verdict, which he announced years before, did not have to be revisited, since it was coming true in real life.

Selected Bibliography

Ian Kershaw, Hitler, Ljubljana 2012

Alenka Simončič, Life and Work of Hinko Smrekar, in: Hinko Smrekar (1883–1942), Ljubljana 2022

The Slovenec Newspaper: 1933 (year LXI) – 11 March (no. 59), 12 March (no. 60a), 15 March (62a); 1934 (year LXII) – 1 August (no. 172a), 2 August (no. 173a), 3 August (no. 174a)

Names of the chapters are taken from the poem The Second Coming by William Butler Yeats.

Author: Michel Mohor, 2022